Overlooking Nose Creek in Calgary. Photo: Jeremy Klaszus

The Bow River, flowing from the Rocky Mountains down through the prairies into Calgary, is a meeting place for friends in the summer, a vista for tourists and a key water resource for the city.

But that could all be different with climate change.

Climate models offer a scientific way of glimpsing what’s coming. If Canada continues on a path where greenhouse gas emissions aren’t curbed, the population keeps booming and there’s only modest technological change, the river, and the city, will look and feel vastly different.

One of the biggest challenges facing Calgary in future is dryer summers, even though rainfall in spring is expected to be slightly higher.

Those heavier spring showers can’t make up for the retreat of glaciers upstream and evaporation thanks to rising temperatures, according to University of Alberta hydroclimatologist Thian Gan.

But exactly when water shortages would occur is unclear. “We may not reach that for a while,” Gan said. “Based on what we understand you could have more water shortage problems but when it will get so hot that the city of Calgary would suffer, we don’t really know.”

The flow of the Bow, which supplies drinking water to the city, could drop by about a quarter under the driest scenarios, according to a 2012 study co-authored by Gan.

Alberta environmental scientist David Schindler, who retired in 2018, has long warned that the Western provinces are heading for a water crisis and not enough is being done to counter climate change.

Unless we are willing to make some drastic changes, even more drastic things will happen — ones that are hard to deal with.

In 2006, Schindler authored a study on the coming shortage—a situation the city has been bracing for. “At about the time I wrote my 2006 water crisis paper, Calgary city officials saw the light,” Schindler said in an email to The Sprawl. “But unfortunately, climate is changing even faster.”

“I think Calgary’s early response will help, but eventually there will be no water for lawns or flower gardens, so suburbs will begin to resemble southern Utah.”

Schindler says that to deal with the coming water crisis, Alberta needs to change its irrigation methods and move away from oilsands industries, which he notes are water-intensive.

“Sadly, our current leadership including hopefuls are still hell bent on 1950s visions that are sure to fail,” Schindler said. “Unless we are willing to make some drastic changes, even more drastic things will happen—ones that are hard to deal with.”

City balks at water restrictions

Since 2006, the province hasn’t allowed for any new water licences for Bow and Elbow rivers, meaning the city is on a finite water supply. According to a June 2018 city report, the city’s license allotment will only last until 2036 if the city meets the demand on the highest consumption days of the year.

Without any positive foreseeable change in supply, the city’s response has been to decrease demand.

City hall has stopped short of implementing residential watering restrictions like Airdrie, Cochrane and Okotoks have.

Frank Frigo, an applied hydrologist working in the city’s watershed analysis group, says the city is finding better ways of capturing and reusing stormwater. The city also pumps potable water from one of the city’s two treatment plants if levels at the other fall too low, he added.

But the city has stopped short of implementing residential watering restrictions like Airdrie, Cochrane and Okotoks have.

In January, Airdrie’s city council approved new restrictions so residents can only water their grass and gardens on certain days of the week. In Cochrane, watering is only allowed between 5 a.m. and 10 a.m. in the morning, and 7 p.m. to 1 a.m. at night.

Okotoks has a mix of both of these approaches, restricting watering to certain days at certain times.

Calgary has no such rules. The city only restricts outdoor watering when it’s deemed necessary by city officials.

'The new normal'

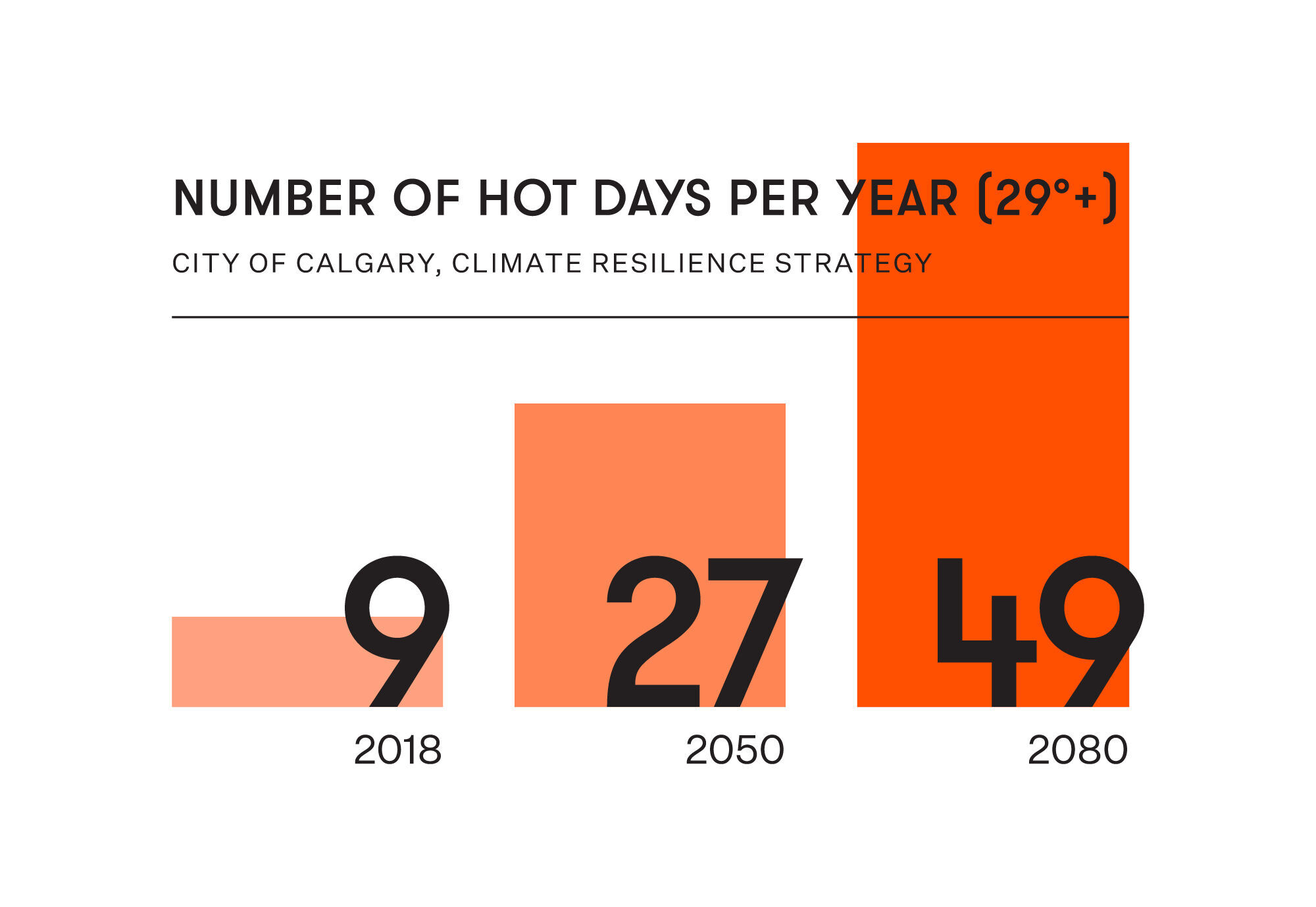

Calgary’s future summers won’t just be dry, they’ll be hot as well.

By 2044, the warmest summer days are predicted to hover around 36 degrees, not factoring in humidity—the same temperature as Calgary’s record high in 2018.

And instead of 30+ degree temperatures being isolated occurrences, they’ll total weeks instead of days.

Prairie Climate Centre climatologist Ryan Smith says the combination of heat with dry days will heighten the risk of forest and grass fires. Forest fires are already starting earlier and staying around longer.

“I think that is increasingly going to be the new normal,” Smith said.

Record high temperatures will also leave Calgarians vulnerable to heat stroke. Heat can physically stress the body to the point where it can’t cope. Marginalized Calgarians will be especially vulnerable.

“Heat is a huge health problem,” said Smith. “Heat being such a big killer is something we don’t tend to think about out west."

"But the truth is when temperatures get that high, anyone who doesn’t have refuge, people out in the streets… they’re at risk.”

Getting ready for extremes

There’s growing evidence that more extreme weather events are on the way due to climate change, including floods, cold snaps, lightning and tornadoes.

Smith explains this has a lot to do with the polar jet stream—a fast moving river of air flowing in a counterclockwise direction high above the earth’s surface. As the Arctic warms, the jet stream becomes weaker, meaning it’s more likely to dip down onto cities like Calgary, bringing with it a blast of frigid air or pulling up hot air from close to the equator.

The goal is, take this information and start doing your adaptation planning now.

Exactly how climate change will affect the jet stream or other features of the atmosphere is still being investigated, and precisely when these extreme events will occur is difficult to predict at the moment.

One thing is clear: Calgary doesn’t want to be ill-prepared when they do.

Researchers like Smith hope that with the data at hand, Calgary and other Canadian cities can shape their infrastructure, and their habits, for the future.

“The goal is, take this information and start doing your adaptation planning now,” said Smith.

“There are thousands of opportunities to invest in our infrastructure.”

Mirjam Guesgen is a freelance journalist specializing in what she calls “science and...” Science and life, policy, culture or the future. Before becoming a journalist, she got her PhD in zoology and completed a postdoctoral fellowship.

This article was originally published in The Sprawl's Spring 2019 newspaper. Become a Sprawl member today to support independent, ad-free journalism (now in Canadian currency!).

Support in-depth Calgary journalism.

Sign Me Up!We connect Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism—but can't do this alone! We rely on our readers and listeners to fund our work. Join us by becoming a Sprawl member today!