Activist Adora Nwofor helped organize the Black Lives Matter at Olympic Plaza on June 6. Photo: Jeremy Klaszus

The case for defunding Calgary police

‘We need people to be able to have their needs met.’

By now you’ve probably seen the hashtags, tweets and photos of protest signs calling to “defund the police.” To some, it seemed like a radical idea before anti-police brutality protests exploded across the globe.

And perhaps, to some, defunding and dismantling police seem like distant “American issues.” After all, our police aren’t like theirs.

But they are. Calgary police—like all police—are tangled in and born of the same systemic web of white supremacy. The issue is not specifically the police in Calgary, although they’re not innocent either.

The issue is the industry of policing.

And like many of the rotted roots that run through this city and contribute to oppression of Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC), policing is a direct consequence of colonialism, a history that is too often forgotten.

When we look at the system through an individual lens—focusing on individual police kneeling with protesters, images that were shared widely in Calgary last week—we risk erasing the root of the issue.

Incarceration is a way to threaten and to control Indigenous people.

The origins of policing as we know it

Because systems of oppression—including policing and prisons—are so deeply entangled with one another, understanding the historical context is paramount.

“Policing and the penitentiary sort of come to Western Canada at the same time in the 1870s,” recounted Ted McCoy, a historian and assistant professor in the department of sociology at the University of Calgary. “So the penitentiary is still fairly new in Canada [in the 1870s]. And it was very new in Western Canada.”

Before then, Indigenous communities were self-governing and “policing” in the modern sense didn’t exist. That changed with colonization.

“There is now a way to punish Indigenous people and to line up the RCMP—or the Northwest Mounted Police, at the time,” said McCoy.

“Incarceration is a way to threaten and to control Indigenous people.”

We need people to be able to have their needs met. They need housing, they need love, they need food.

It’s those roots of criminalization that need attention, say local activists.

“We need people to be able to have their needs met. They need housing, they need love, they need food,” said local activist Adora Nwofor, who helped organize Saturday’s Black Lives Matter vigil at Olympic Plaza.

Those unmet basic needs—adequate and affordable housing, access to mental health resources, clean water and so on—contribute to the foundation of what we as a society have deemed “criminal,” and therefore fall under the vast scope of policing.

In Calgary, 14% of property taxes go to police

Calgary police receive about 80% of their funding from the City of Calgary—just over $400 million—with the rest coming from the province, fines and user fees.

“If we're looking at the reality of the situation in Calgary, we have about 14% of our residential property tax dollars go into police services,” said Demi Okuboyejo, a student-at-law who focuses on social justice and policy. “We can compare that to the amount of property tax that goes to social programs and services like affordable housing—and that's less than 2%.”

That funding goes towards the salaries of officers and “civilian positions” (peace officers, administration, training and financial support staff, to name a few).

They’re responsible for a broad range of duties, which ranges anywhere from ticketing transit riders to criminal investigations to wellness checks to civil disturbances and victim support.

Move the money away from police departments and funnel it into social programs.

This umbrella of policing is part of the problem. This system expects officers to do the jobs of a number of fields and the communities who are directly impacted—namely, BIPOC—are often left out of the conversation.

“That policy choice or disparity in those numbers has implications for Indigenous people, for Black people, for people of color, for poor people, for low-income and homeless Calgarians,” Okuboyejo said.

Where do we go from here?

A new path for tax dollars

Defunding police departments is not a concept as new or “radical” as it may seem. Black intersectional feminists have been speaking about it for years—but only recently, after it’s hit the mainstream news cycle, have people begun to listen.

The framework is simple: move the money away from police departments and funnel it into social programs and community organizations who specialize in the fields that officers are not trained for.

And that’s exactly what Maki Motapanyane, a professor at Mount Royal University’s department of women and gender studies, says people need to understand beyond the hashtag.

The system of policing is not broken. It’s fulfilling exactly what it was historically intended to: punishment.

Some are calling for complete abolition of police departments—but for others, "defund the police" means something different.

“It's important for people to understand that it's not an argument for completely eliminating funding for police or eradicating the police,” Motapanyane said.

“It’s an argument for reducing police budgets and for reallocating those funds to services and agencies that would address issues around structural inequity. So this means things like proper housing, good education, access to good medical care and mental health and addiction services.”

And maybe, the funds could go back to the anti-racism initiatives that the UCP defunded in fall 2019. Or free-fare transit, while we’re on the topic of ways to decriminalize marginalized existence.

Limiting encounters with the police is just one piece of the puzzle in dismantling. But the funding must go back to help address the issues which shouldn’t have been criminalized in the first place.

“Think about bylaws that are basically bylaws that criminalize homelessness,” Okuboyejo said.

“You're giving people tickets for loitering or like those kinds of things when they are homeless. Where are they supposed to go?”

Beyond that, defunding is not to be confused with a reformation of the system, which implies that it can be fixed. The system of policing is not broken. It’s fulfilling exactly what it was historically intended to: punishment.

We do have a problem with racialized bias in policing.

“Canadian data tells us that yes, we do have a problem with racialized bias in policing,” Motapanyane said.

“If we look at Canadian numbers, they show that there's disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous and Black people in Canada and that Indigenous and Black people in Canada are overrepresented in deadly force encounters with Canadian police.”

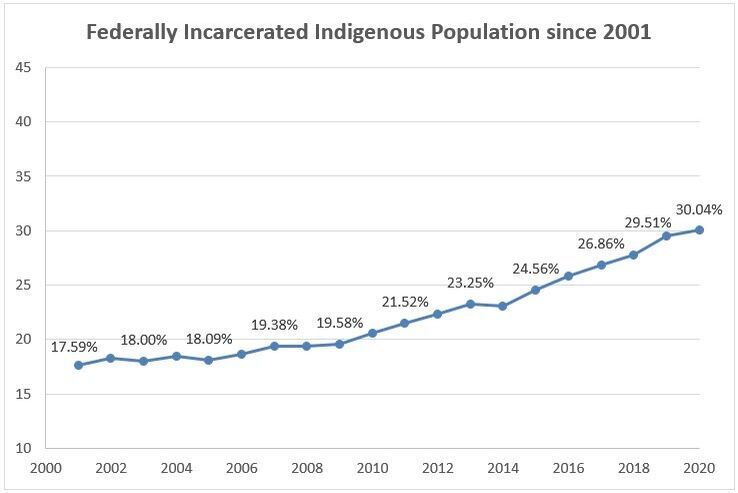

Indigenous people account for about 5% of the population. In January, Ivan Zinger, the Correctional Investigator of Canada, noted that more than 30% of the federally incarcerated population is now Indigenous.

In 2018, Black people made up about 3% of the population but 8% of the federal prison population.

Motapanyane argues that defunding police can mean withholding pensions from officers found to be involved in problematic and violent cases, making them personally responsible for their legal costs if they do get in trouble (rather than the police department paying for it) and ensuring that violent officers are not re-hired.

“It's not just, ‘Oh, fire them or cut their pay in half.’ There's a lot of money that's being spent on things that don't really make sense... and that money can be redirected.”

'I need the police to stand down'

Advocating for big, impactful change like this can be laborious, especially in a majority white city like Calgary, where proving that racism exists is half the battle.

The city’s 2019 Citizen Satisfaction Survey even states that over half of the polled population believes that we should be investing more in the Calgary police and that 57% are “very satisfied” with the job that the department is doing.

But is that an accurate representation?

Nwofor has been organizing in the city for years and was notably involved with the Women’s March. Most recently, she and other Black activists in Calgary hosted the Black Lives Matter vigil in Olympic Plaza on June 6.

Although officers were present, the police were specifically not invited.

The police wanted to be at the front — get out of the way. This is not about you.

“Organizing is lonely and it is exhausting,” Nwofor said. “And it sometimes feels like you're doing nothing over and over and over again. So to be the person or a group of people that are being watched very carefully at every moment—it's nerve-wracking because you really want the message to be heard, not the tactics to be judged.”

Nwofor said she left the march against police brutality on June 1 because she noticed police walking in front of the protesters in an act of “solidarity.”

“The police wanted to be at the front—get out of the way. This is not about you,” she said. “You're protecting us from the police? Like the police are going to stand in front of the police? Because right now, we're talking about the police.”

“This doesn't make any sense.”

After the marches on June 1 and 3, photos of Calgary officers taking a knee with protesters circled on social media. Many took this as a sign of hope, but this further pushes the narrative that “ours are not like theirs” and waters down the message in the process.

“I need the police to stand down,” Nwofor said. “Why are you kneeling at a protest about you kneeling on somebody’s neck? It's so grotesque.”

Tough and uncomfortable conversations need to happen in this city if Calgarians want to ensure that activists don’t feel like they’re doing nothing over and over again.

And defunding the Calgary police department is one of those conversations.

“The mayor, the police chief, city council—those are the people that can reallocate funds away from policing and towards things like social programs,” Okuboyejo said.

Hadeel Abdel-Nabi is The Sprawl’s staff writer intern.

CORRECTION 06/09/2020: We originally misidentified Demi Okuboyejo as a lawyer; in fact, she is a student-at-law. As well, we originally said the Black Lives Matter vigil was on Sunday, June 7; in fact, it was Saturday, June 6. The Sprawl regrets the errors.

Now more than ever, we need strong independent journalism in Alberta. That's what The Sprawl is here for! When you become a Sprawl member, it means our writers, cartoonists and photographers can do more of the journalism we need right now. Become a Sprawl member today!

Support in-depth Calgary journalism.

Sign Me Up!We connect Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism—but can't do this alone! We rely on our readers and listeners to fund our work. Join us by becoming a Sprawl member today!