The Stampede Elm is believed to be at least 120 years old. Photo: Jeremy Klaszus

A little perspective on the arena deal

The world has changed.

On weekends, The Sprawl sends out an email newsletter called Saturday Morning Sprawl. You can subscribe here. Here is this week's dispatch.

Know who's had a really great week?

This tree in Victoria Park.

The Stampede Elm, as it's sometimes called, is one of the oldest elm trees in the city. It's also rooted right where the new Flames arena (a.k.a. event centre) is—or was—supposed to go.

This old tree has quietly outlived booms and busts and all manner of human joy and folly. Its precise age is unknown, but it's believed to be at least 120 years old, one of the last holdouts of a working-class neighbourhood that was razed for continual Stampede expansion and parking lots in recent decades.

Now it looks like it will stand a little longer.

After watching Wednesday's city council meeting on the arena deal's end—which set off a torrent of hot takes—I walked over to visit the old tree. In search of the long view, I guess.

This tree has witnessed various sports and entertainment venues rise and fall in the neighbourhood over the years. The ballpark where the Calgary Bronchos played baseball starting in 1907. The arrival of professional hockey in the 1920s at the Victoria Arena, Calgary's first pro hockey barn—a literal barn, as it was also used for horse shows and the like.

Then, in 1950, the Stampede Corral opened.

This was allegedly rapturous at the time.

"It appeared to be a replica of an old Roman amphitheatre, where ancient sports were carried on," wrote one letter-writer to the Calgary Herald, describing the view from his seat.

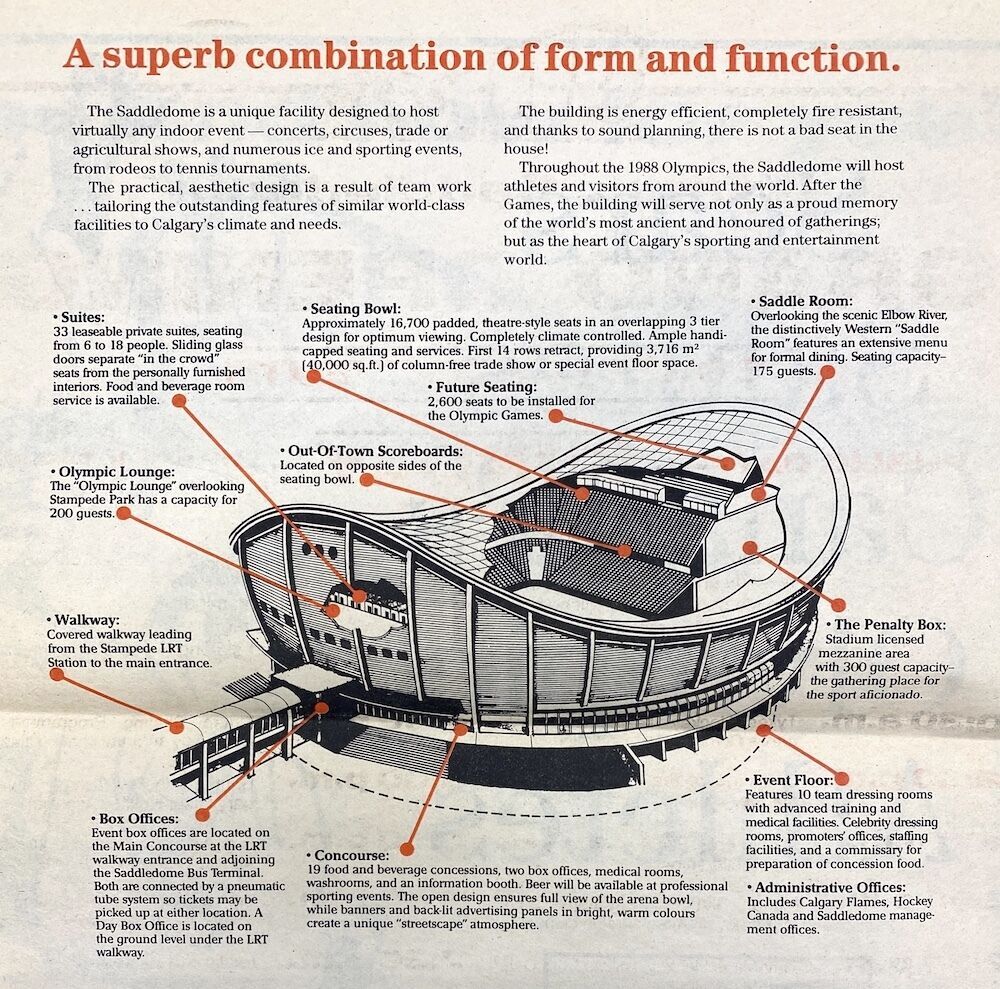

And then, in 1983, Calgary got the Olympic Saddledome.

It's funny to look at the news coverage from that era, because a lot of what was said then is current again today. (I find this happens all the time on all kinds of issues. It still surprises me. I'm not sure why.)

At the time, there was indignation that big-name concerts were bypassing Calgary and going to—you guessed it—Edmonton.

"For example, performers such as Billy Joel, Rod Stewart and Roxy Music have played Edmonton's Northlands Coliseum but avoided the Corral in Calgary, with its smaller crowd capacity of about 7,000," reported the Calgary Herald in June 21, 1983, under the headline: "Saddledome will put city on rock map."

Our Edmonton arena envy was such that, in the early 1980s, Calgary city council originally asked that the design of the new arena be based on Northlands Coliseum.

This evolved into the saddle-shaped design that has helped define the city's skyline for the past four decades. At the time it was hailed as a marvel of human engineering—"one of the world's most unique and versatile coliseums," to quote the promotional material of the day.

Now it is regarded as wildly inadequate.

You could say that in the last century, Calgary got a new hockey arena every 30 years or so.

But the 21st century won't be like the 20th—in all kinds of ways.

That, I think, explains some of the fury issuing forth from the likes of Herald and Sun commentators this week. They want so badly to prop up the world that was—even if it means giving billionaires like Murray Edwards what they want (that is, after all, just how the world works!). They believe that a new arena can help Calgary turn a corner, that the same crowd that turned Victoria Park into a bunch of parking lots can help reinvigorate the same area they sucked the life out of.

That the leaders of the old world can usher us into the new.

These districts are largely built for the world that was.

But the reality is that the entire entertainment district, as mapped out by CMLC—"the city's gentrifying arm," a friend quipped to me the other day—was envisioned in a different time. Not just the arena, which is now being portrayed as the lynchpin of the entire plan, but also the BMO Centre expansion that is currently underway.

The pandemic isn't the only threat, nor are supply chain issues and rising costs. These projects are built with the hope of air travel continuing unabated and conventions being a growing business in the future.

("Cities are overbuilding convention centres, missing all the signs of the changing marketplace, failing to grasp how people communicate and chasing a dying business model," wrote former Calgary city planner Rollin Stanley in 2019—and that was before the pandemic.)

These districts are largely built, in other words, for the world that was.

Here's another way of looking at the events of the past few weeks: perhaps the arena deal functioned more or less as it should have. There are checks along the way for a reason.

On Wednesday, council unanimously voted to revisit the arena project—"appreciating that global pandemic and economic conditions may have made originally negotiated agreements on an event centre non-viable."

In the 1980s, the Calgary Olympics gave the impetus for the Saddledome to proceed swiftly to completion, despite the controversies surrounding it, including cost overruns.

Forty years later, in the midst of a global pandemic, we're looking at no Olympics, no new arena (for now) and, as was reported this week, a third of the city's downtown office space empty.

The world has changed. Now we don't know what to do.

And maybe that's okay.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.