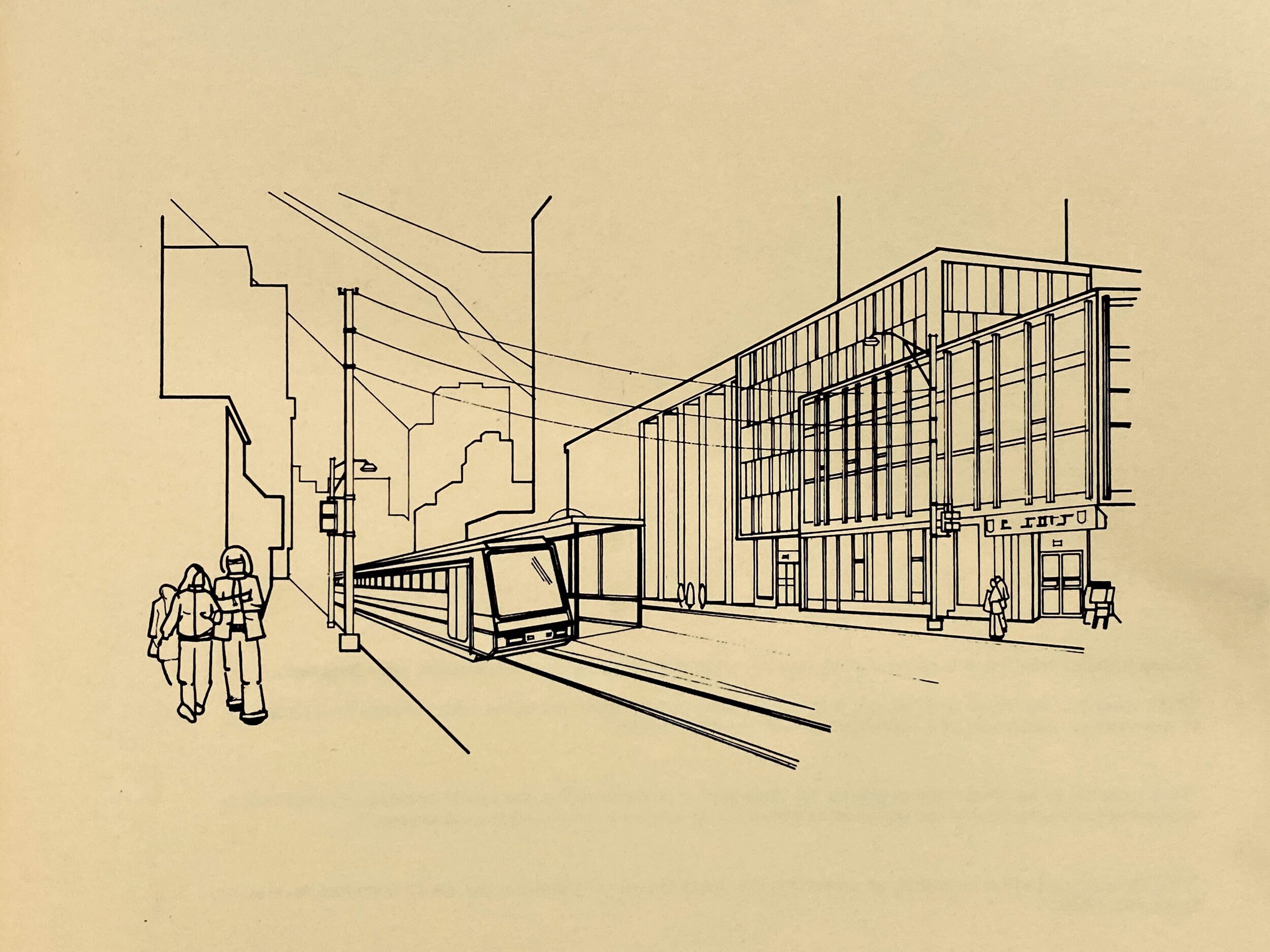

Rendering from "Light Rail Transit for Calgary" plan, 1976.

A tale of two LRT lines

In 1977, the CTrain almost got derailed.

On weekends, The Sprawl sends out an email newsletter called Saturday Morning Sprawl. You can subscribe here. Here is this week's dispatch.

A transit update at city hall this week got me thinking about two LRT projects: the one we already have, and the one we're slated to get.

Council’s executive committee heard Tuesday that it will be difficult to keep the first stage of the Green Line within its $5.5-billion budget. Don Fairbairn, chair of the Green Line board, noted that infrastructure projects across the country are facing rising construction costs.

"We have a low level of confidence in our ability to deliver all of stage one within available funding," Fairbairn said. "We are committed to managing costs and risks, and to building phase one from Shepherd to Eau Claire—and, if possible, from Eau Claire to 16th Avenue North."

In other words: Get ready to adjust expectations.

Darshpreet Bhatti, who took over as CEO of the Green Line project last summer, told council members that pricing for utility relocation work in the Beltline is already coming in higher than expected. Bhatti said city admin is working on ways to reduce the financial burden of borrowing for the project, along with "value engineering" the Green Line.

Doug Morgan, the city's transportation GM, urged council members to take the long view on the project and recall the city’s first LRT line, which opened in 1981 amid an economic downturn and a hurting downtown.

"Who knew the start of LRT, with that kind of in-the-doldrums outlook, could turn out to be the success it has been in Calgary?" said Morgan.

Today it’s hard to imagine Calgary without the CTrain. But Morgan's comment got me wondering: What did that first stage of Calgary's LRT look like before it was built? Did it look like a sure bet? And how might that inform how we look at the Green Line today?

On May 25, 1977, the same day Star Wars opened in theatres (yes, seriously), Calgary city council green lit Calgary's first LRT line.

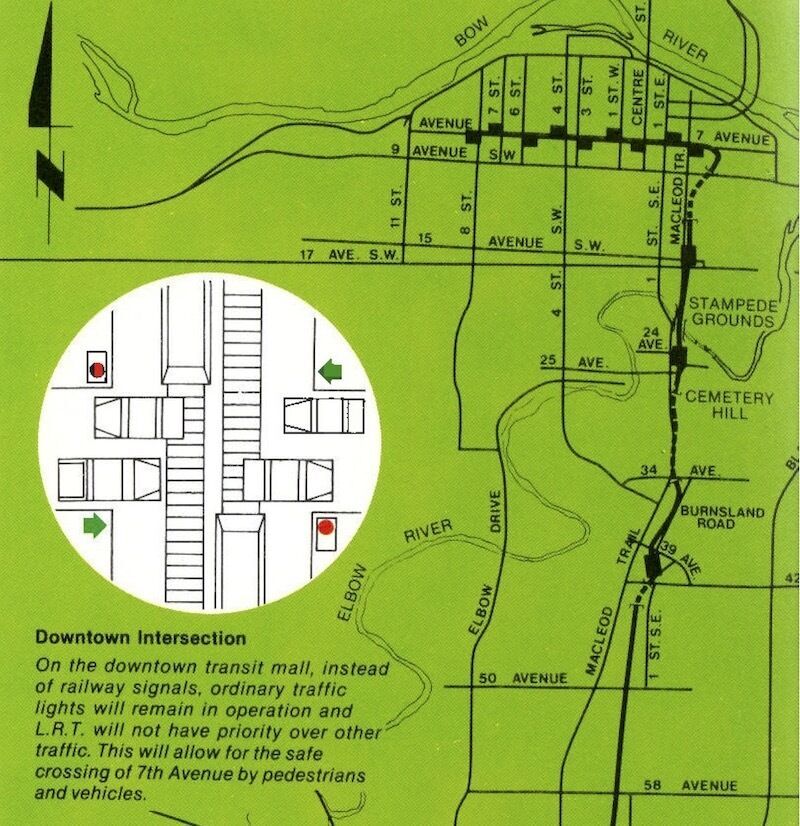

Mayor Rod Sykes’s council approved $144 million for a 12.5-kilometre track that would run from Anderson Road in the south into downtown.

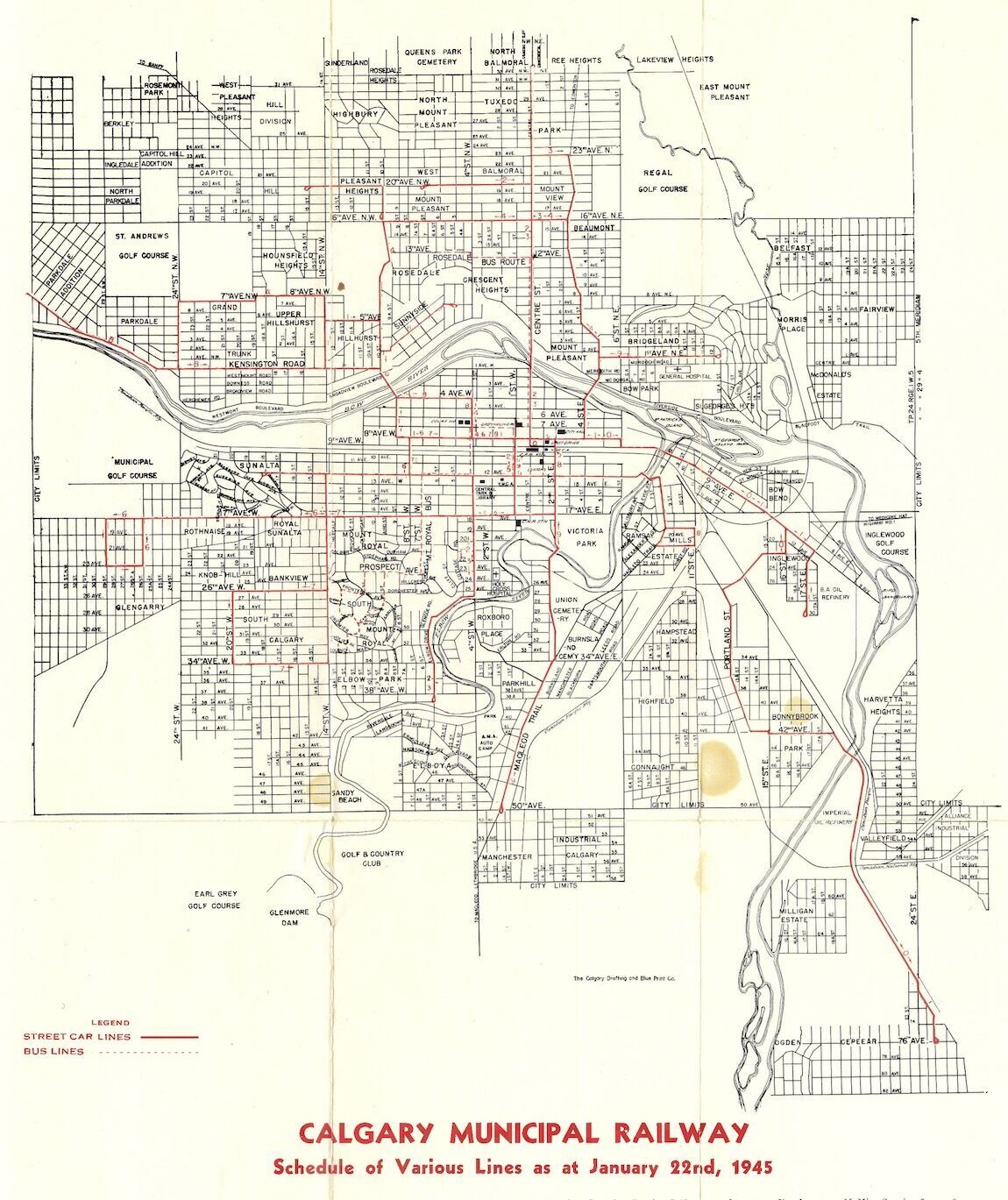

At the time, many Calgarians still had memories of riding the city's elaborate streetcar network, which ended service in 1950 as the aging rail service was supplanted by new buses—of both the diesel and electric-trolley variety.

"The salesmen did a pretty good job of convincing us that the bus was the transit of the future," city transportation director Bill Kuyt, who championed LRT alongside Mayor Sykes in the '70s, told the Calgary Herald in 1980.

Less than two decades after city hall ended rail transit, city planners were looking at how to put it back.

In the 1960s, city hall embraced what it called a "balanced plan" for transportation. In retrospect, we can see its imbalance, as it vastly favoured the private automobile over transit and other modes, creating wide thoroughfares like Deerfoot Trail and entrenching the car-dependent city we have today.

Starting in the mid-'60s, city consultants started floating the idea of a rapid transit system for Calgary, possibly with a subway running beneath 8th Avenue. This idea evolved into a new riff on old the rails Calgary had lost: light rail transit, or LRT.

It wouldn’t run under 8th Avenue, but along the surface on 7th Avenue, where trains would be forced to stop for traffic lights just like cars (and Calgarians have been cursing this decision ever since!).

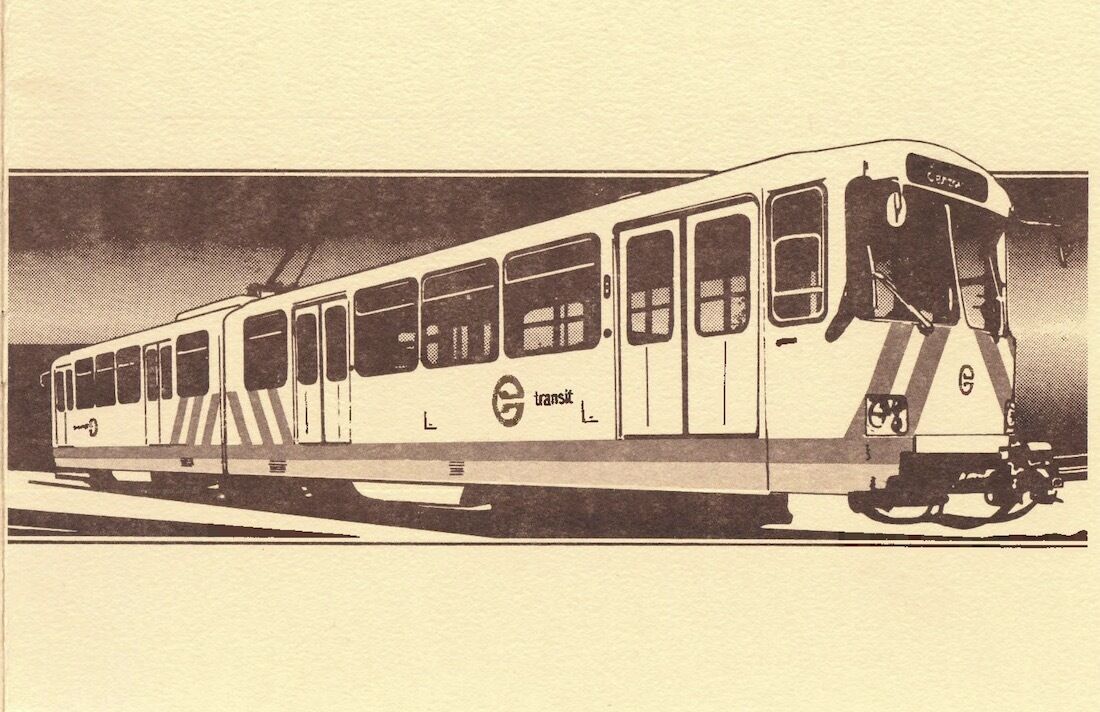

When the Herald sent a reporter to an LRT car factory in Dusseldorf in early 1977, the correspondent found the West German company couldn’t keep up with demand. “The prime spur to action is an ever-growing tide of automobiles creating congestion and causing the disintegration of urban cores,” reported the Herald.

Cities were re-embracing the streetcar—although the car was still priority number one. Numerous Calgary newspaper articles from the time noted, both positively and pejoratively, that LRT was the old streetcar in disguise.

After city council gave the green light for LRT in May 1977, months away from a municipal election, all hell broke loose.

Council faced intense blowback. LRT quickly became a campaign issue. City hall was moving "too far, too fast" on LRT, warned The Albertan (the precursor to the Calgary Sun). The arguments made that summer will sound familiar to anyone following more recent fights over transit: It was too risky. Too costly. The city didn't have enough information. There wouldn’t be enough riders. Buses were what Calgary had, so we should stick with buses.

"LRT conceived in haste," read the headline of one Herald column. "Will new council 'repent’”?

Mayoral candidate Ross Alger certainly hoped so. On the campaign trail, he tapped into citizen frustration, demanding a public hearing and a rethink of the project. LRT shouldn’t be considered until the road system was complete, he argued. "All Calgarians would benefit by the delay!" he wrote.

Some councillors, like Virnetta Anderson, saw beyond the anger of the moment. "The benefits gained from LRT will be worth the cost," she told the Herald that October.

But Alger won that fall—along with seven other new council members, most of who were, like Alger, LRT skeptics.

In other words: Mere months after council approved LRT, Calgarians elected a mayor who vowed to revisit the project. "Some of the rapid has gone out of Calgary's rapid transit system," reported the Herald that December.

As mayor, Alger did indeed seek to halt the project, but cars had already been purchased. It would have cost millions to reverse council's original decision.

The new council chose to proceed with LRT under the direction of civil engineer Oliver Bowen (read more about Bowen in Afros In Tha City: Ode to the CTrain, A Black Invention).

Alger eventually mellowed, conceding in his 1980 campaign material that he was "satisfied" that the LRT system being constructed was, as it turned out, "a good one" for the city.

Alger, however, lost the 1980 election to combative CFCN TV reporter Ralph Klein.

Ironically, the construction of the CTrain—decided before Alger was elected, and completed after Klein took over—is counted among the accomplishments of Alger's brief mayoral tenure.

Shortly after Calgarians elected Klein as mayor, it became clear that the original $144 million wouldn't cover the full cost. Council approved two rounds of further spending on the project.

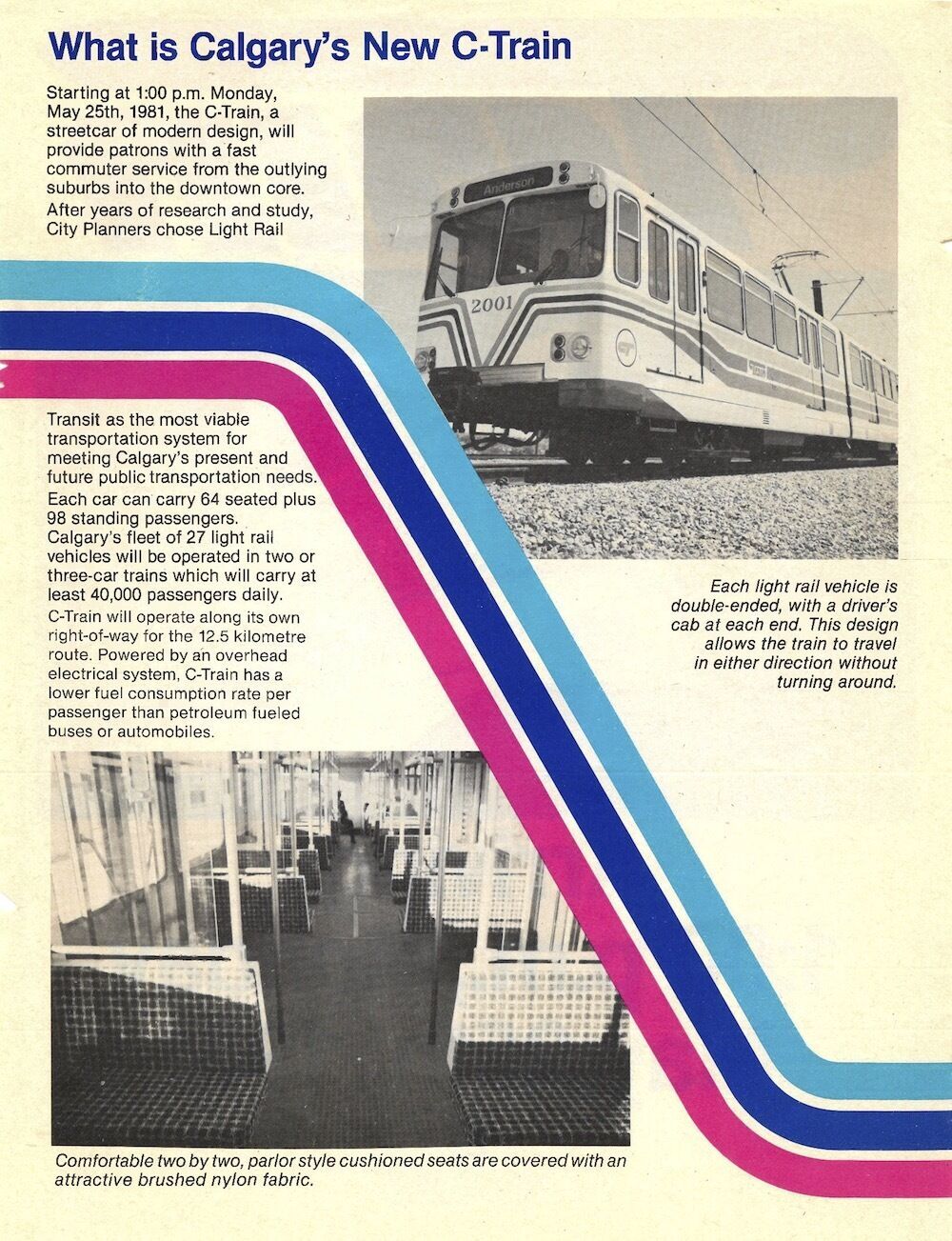

When the CTrain opened in May 1981—"a streetcar of modern design," noted city promotional material—its cost had risen to $175 million, up from the original $144 million.

The rest is history. The CTrain took off. Mayor Ralph Klein went on to fight for the two north legs of the train, scrapping with the province for funding to make them happen. The CTrain's expansion in the 1980s was plenty contentious too—but that's another story.

Of course, there are significant differences between the 1981 LRT and the Green Line of today.

The first leg of the LRT was built mostly at grade, with some cut-and-cover construction for shallow tunnels. All the stations were on the surface. The Green Line involves tunnelling beneath downtown and building four underground stations—a much more complex and expensive endeavour, one that city hall has been putting off for half a century.

The first stage of the Green Line, from Shepherd in the southeast to 16 Avenue N., is also 20 kilometres, whereas the 1981 line was 12.5 kilometres.

Still, history shows that building LRT is not easy. It has always been politically fraught and full of various uncertainties along the way. It’s easy to take today's CTrain for granted. But these projects were borne of vision, conflict, compromise, tenacity—and, yes, financial investment.

The councils of the late '70s and early '80s had to navigate the biggest public works project in the city’s history, public skepticism and ballooning budgets.

Some forty years later, Mayor Jyoti Gondek and the council of 2022 face similar challenges in a much more uncertain world.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.