Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!

When Albertans took to the streets after the murder of George Floyd in June 2020, some took note of the significant number of people who turned out in support as unexpected, and perhaps signalling a sea change of some kind.

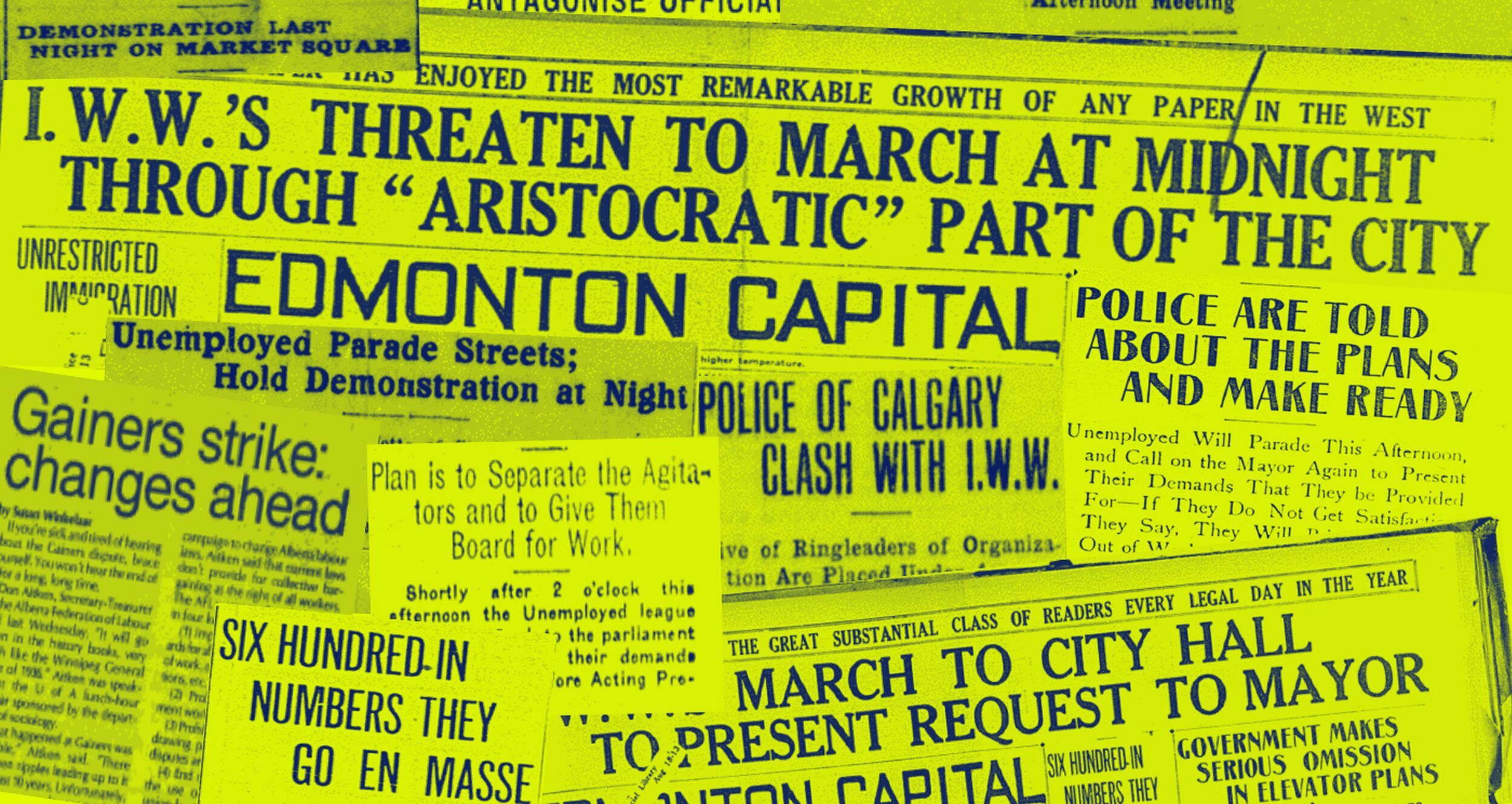

But Alberta has long been a place where people march, organize, and otherwise agitate for change from their local or provincial authorities.

What can we learn about a government from how it chooses to respond to protests, demonstrations and other forms of organized civic opposition?

It might surprise some to learn that organized activism in early 20th-century Alberta was often centred on unemployment and class divides, and frequently led by groups like the Industrial Workers of the World or other socialist and communist leaders.

In May 1914, for example, 500 unemployed men marched through Edmonton protesting government inaction on unemployment and economic inequality. The “mob,” as the Edmonton Journal called the group, “tramped about the streets” and cheered speeches by organizers before heading to the legislature where a delegation met with acting premier Charles Stewart, who disputed that there was no work available.

Authorities were similarly unsympathetic in April 1922, when hundreds of unemployed men in Calgary protested the closing of a Victoria Park bunkhouse, which provided barracks-like temporary housing for single men. The Calgary Herald reported that 300 men “took possession of the council chamber, and demanded an interview with the mayor and commissioners." The mayor, Samuel Hunter Adams, refused and ordered police to expel the men.

The period during World War II saw a significant increase in unionization, labour historian Alvin Finkel says, but the post-war nationalism and Red Scare of the new Cold War cooled off any form of organizing or protest in Alberta. “No one wanted to be seen as a communist,” he said.

The 1960s are today synonymous with protest, from the anti-war movement to Indigenous rights and civil liberties in the United States. While these were not absent from Alberta, according to Finkel the degree of protest overall was greatly diminished in Alberta relative to elsewhere in Canada.

No one wanted to be seen as a communist.

“During the period of oil and Social Credit, a lot of [activism and agitation] is pushed back,” he said. “There’s a certain Alberta culture that comes out of that oil period, particularly in the 1970s.”

That low-key era changed in the 1980s, as the unsustainable prosperity from oil slammed into a wall, and unemployment soared once again. This would be what labour historian Winston Gereluk called “the most militant decade in Alberta labour history.”

There were numerous strikes and protests during this period, but the most prominent was the walkout by employees at the Gainers meat-packing plant in Edmonton in 1986.

Gainers was owned by Peter Pocklington, an Edmonton businessman who also owned the Oilers and is probably most infamous today for trading Wayne Gretzky to Los Angeles. But in 1986, he was hated by workers for using strikebreakers, or “scabs,” when Gainers employees walked off the job in protest over wage rollbacks and pension reductions.

The Gainers strike was a seminal event for the labour movement and organized activism generally in Alberta. Per the Edmonton Journal, more than 6,000 people attended one demonstration at the legislature—the largest such demonstration since the Great Depression—and workers picketed the streets constantly.

“Everybody supported them,” Finkel said, “because people saw this as pivotal: If we can win this one, if a guy like Pocklington is forced to pay his workers properly, then we can fight for an end to these exceptionally low wages that are becoming common.”

After six and a half months, the provincial government under new premier Don Getty offered Pocklington $61 million in loans with sweetheart terms; a new collective bargaining agreement was reached that froze wages for two years, followed by a small raise, and protected pensions. Dave Werlin, then president of the Alberta Federation of Labour, later said the strike was “a watershed in the struggle of working people in this province.”

Alberta’s economic troubles were prescribed austerity by its conservative leaders, and Ralph Klein upped the dose when he was elected in 1992.

I’m reminded of what premier Ralph Klein used to say. ‘If a day goes by and there’s not a protest, I’m wondering what I’m doing wrong.’”

The Klein cuts would devastate Alberta society and create a lasting infrastructure deficit. There were protests against the decimation of health care, education and the arts—but Finkel characterizes them as “ritualized” and “dispirited,” as people knew nothing would change.

But the 1995 strike by health care laundry workers whose jobs Klein was outsourcing was different. The workers, mostly immigrant women of colour, walked off the job illegally without their union leadership. By the time the government backed down ten days later, thousands of hospital workers had joined the strike in solidarity.

Generally speaking, these protests have been against conservative policies by conservative Alberta governments. But in 2015, Alberta elected its first centre-left government in nearly a century.

When the NDP announced a bill in November 2015 that would extend occupational health and safety regulations to farms and ranches, many farmers were upset about it. The following week’s announcement that Alberta would introduce a carbon tax made a lot more people upset.

The government drew fire on its farm legislation, Bill 6, for what many argued was a poor consultation process. Though the bill brought Alberta largely into alignment with other provinces, the lack of communication meant that farmers were caught off-guard. The carbon tax, meanwhile, had direct relevance to far more people, and many were confused or angry about it.

There were several notable protests between the announcements and January 1, 2017, when the carbon tax took effect. Some were primarily focused on one thing, like Bill 6, but others featured a medley of outrage. There was the "kudetah" supported by those who felt the NDP’s electoral win was somehow illegitimate (sound familiar?); and the "lock her up" chants at a legislature rally led by a federal Conservative leadership candidate (sound familiar?).

The NDP held firm to the carbon tax, defending it along with their broader climate policy.

When the UCP took office on April 30, 2019, they only had to wait a few days for their first protest: thousands of students across the province walked out of classes to protest the new government’s policy on gay-straight alliances (GSAs) in schools. That act of defiance and other protests, including an NDP filibuster of the bill, were ignored by the government.

Significant protests across the province over the UCP’s cuts to public funding and jobs also had little impact. But the UCP’s most notable response to protest is undoubtedly Bill 1.

In February 2020, during the Wet’suwet’en nation’s standoff with the RCMP and Coastal Gas Link, solidarity protests spread across the country, including Alberta. In Edmonton, Wet’suwet’en supporters erected a blockade of the CN railway, one of several such actions that disrupted national rail service.

The UCP quickly took the side of the energy company and the police: Jason Kenney said the protests amounted to “anarchy” that “ultimately will imperil public safety and health.”

(That last part is a bit of foreshadowing that we’ll return to later.)

If those words seem like hyperbole, the government’s response was fit to match. Bill 1, also known as the Critical Infrastructure Defence Act, made it illegal to protest on “essential infrastructure,” while also empowering the government to arbitrarily deem any infrastructure as “essential.”

In a case of heavy-handed screenwriting, that bill received royal assent as Albertans joined others around the world in taking to the streets following the murder of George Floyd. Like the railway blockade, the Black Lives Matter protests were peaceful demonstrations about large and systemic issues—colonialism, white supremacy—as well as particular events. But though the BLM protesters were much larger in number, they did not directly threaten oil and gas interests.

Whatever the reason, the UCP struck a starkly different tone.

Who would have guessed that an arch-conservative like Jason Kenney would face right-wing protests for not loving individual freedom enough?

“I denounce racism in any form and police brutality anywhere that it occurs,” Kenney said when asked about the local protests. “We need to acknowledge that we’re not perfect in Canada, that we always need to strive to do better in ensuring equality of all before the law.”

A few months later, Kenney was called out for his tepid response to a racially motivated attack on anti-racism protesters in Red Deer. This double-standard approach to judging the validity of an act of protest has appeared more than once.

No government in a century has faced a crisis like COVID-19. Along with the practical challenges of public health and safety, there are social, cultural and political realities at play that can upend expectations. For example, who would have guessed that an arch-conservative like Jason Kenney would face right-wing protests for not loving individual freedom enough?

Alberta has never had a real lockdown during the pandemic as other jurisdictions have, instead implementing various public health measures designed to meet the bare minimum, at best. Despite this, many have been outraged by the continuing restrictions.

These far-right groups are an amalgam of grievances under the banner of not wanting to wear a mask. The anti-lockdown protests have appropriated the language and framing of genuine fights for justice, while being rooted in a spectrum of motivations ranging from individual selfishness to white supremacy and fascism.

The UCP response to those openly defying laws and public safety has been markedly different from how the government reacted to Indigenous blockades that affected fossil fuel interests. When a man was arrested outside the legislature in May 2020 for leading a protest against public health orders, the premier sprang into action, publicly questioning the arrest. “The right to peaceful protest is a fundamental right that includes both the freedoms of speech and assembly,” Kenney said in a statement.

Rallies and protests against the restrictions continued across the province. Even a quarter of the UCP’s MLAs joined in.

The way [governments] respond to protest tells you something about who their supporters are.

The problem is that the people protesting are also likely to be conservatives and therefore UCP voters. Kenney, who had built his brand on right-wing obstinance, now found himself painted into a corner, trapped between the politics and the science. “The anti-maskers are a huge part of their voting base, so they treat them with kid gloves,” Finkel said.

Only recently has the government shown signs of pushing back. The pastor of GraceLife Church was arrested. The organizers of an anti-mask rally disguised as a rodeo were charged with breaking public health laws. Kenney himself took protesters to task after a rally where the name of Dr. Deena Hinshaw, the province’s chief medical officer, prompted chants of “lock her up!” (Sound familiar?)

Then again, Kenney also said this: “I’m reminded of what premier Ralph Klein used to say. ‘If a day goes by and there’s not a protest, I’m wondering what I’m doing wrong.’”

Organized public protest can spur a government into action, or dissuade it; but there are many factors that make mass protest successful, and not every demonstration achieves the desired government response. “The way [governments] respond to protest tells you something about who their supporters are,” Finkel said. “You can’t really divorce political parties from a social class base.”

Perhaps, then, what’s more telling is which protests a government listens to and which it dismisses.

“If the people protesting are from the bottom rungs of society and you’re not willing to help them, then who are you helping?” Finkel added. “Why are you even there?”

Taylor Lambert is The Sprawl's Alberta politics reporter.

CORRECTION 07/08/2021: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the name of the Industrial Workers of the World. The name has been corrected and The Sprawl regrets the error.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!