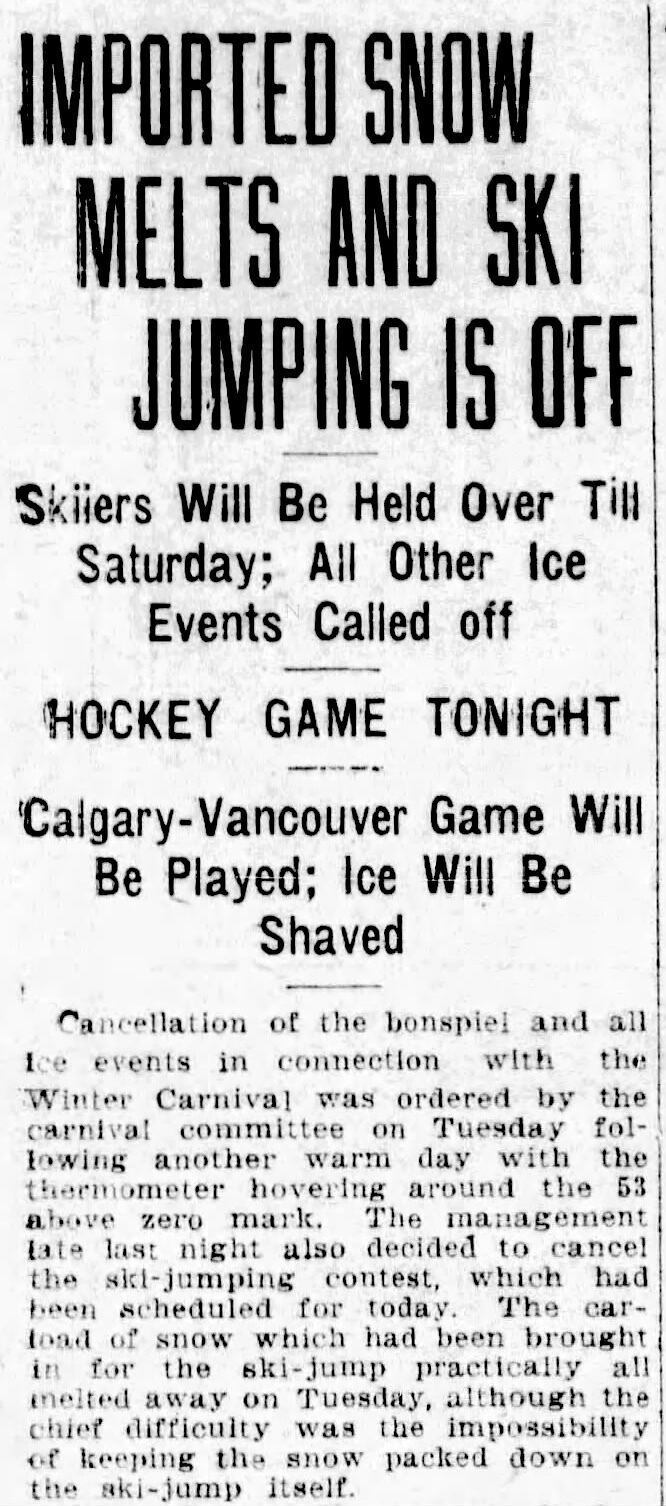

Calgary Exhibition ski jump in 1921. (Glenbow Archives, University of Calgary)

Calgary’s original winter games: The dizzying Stampede ski jump

Look up — look waaaay up.

Throughout Calgary’s history, promoters and schemers have tried various ways to "wow" local citizens while putting the city on the map for the wider world.

Sometimes, as with the Calgary Stampede or the 1988 Olympics, these schemes successfully take flight. Others launch with promise but soon crash back to Earth.

This is one such story.

More on the little-known Stampede ski ‘hill’

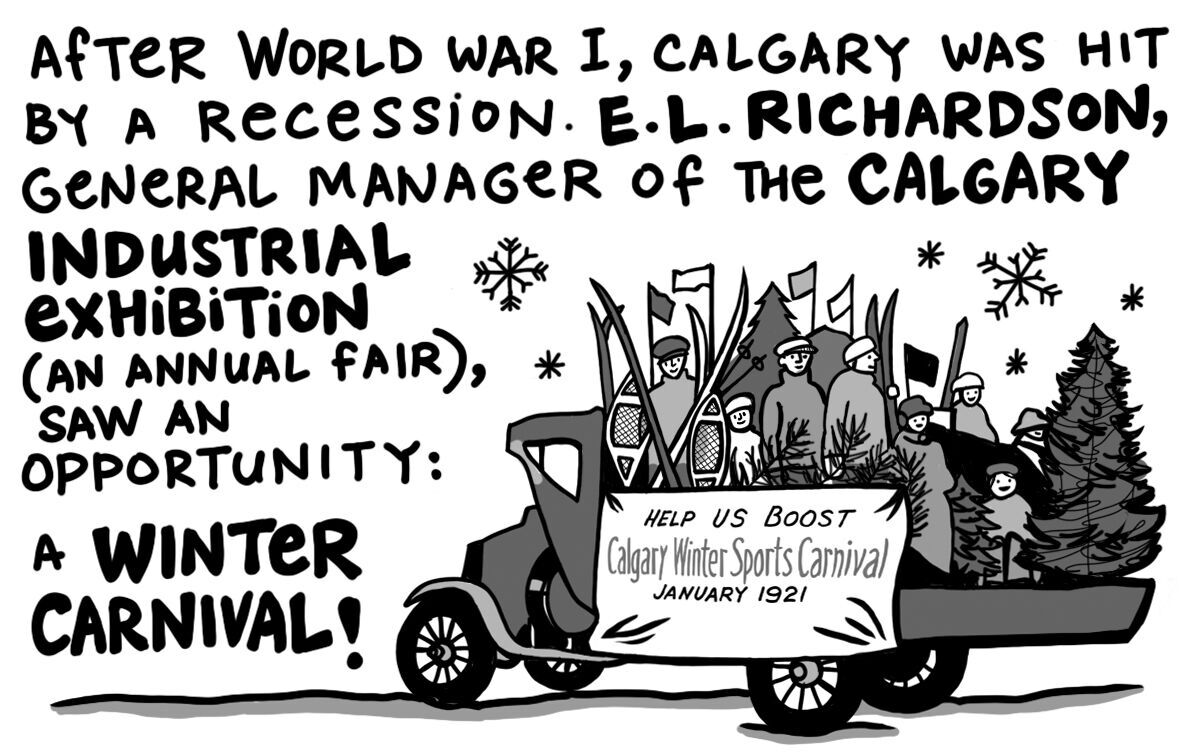

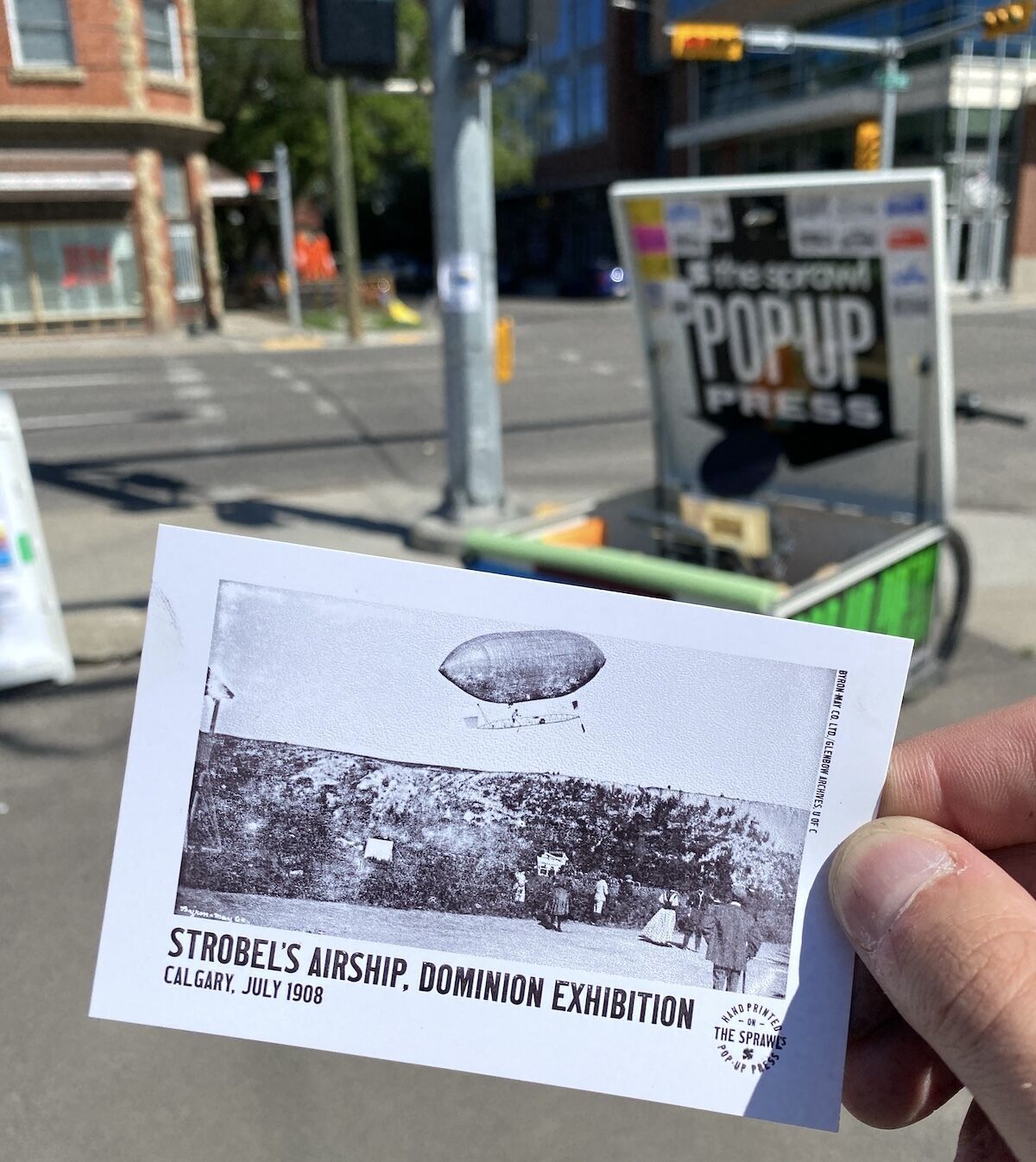

E.L. "Ernie" Richardson knew how to put on a good show.

He'd brought all kinds of daredevilry to the Calgary Exhibition as its general manager—including, in 1908, a giant airship that rose above the city but later caught fire on the ground.

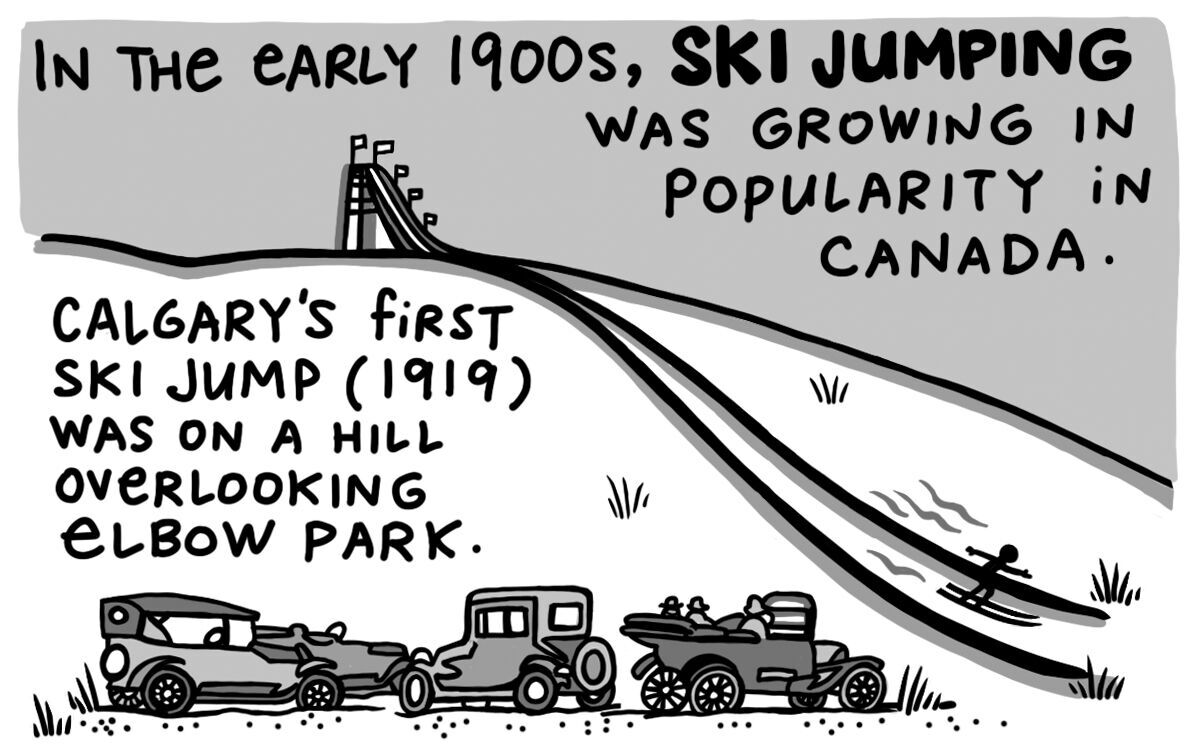

In the early 1920s, the Calgary Winter Carnival, which took place on the Stampede grounds we know today, was a big deal. The city's population was just over 63,000. The Exhibition flooded the race-track oval for speed skating. There was also curling, hockey, ski racing, figure skating, snowshoe races and skijoring (skiing behind ponies).

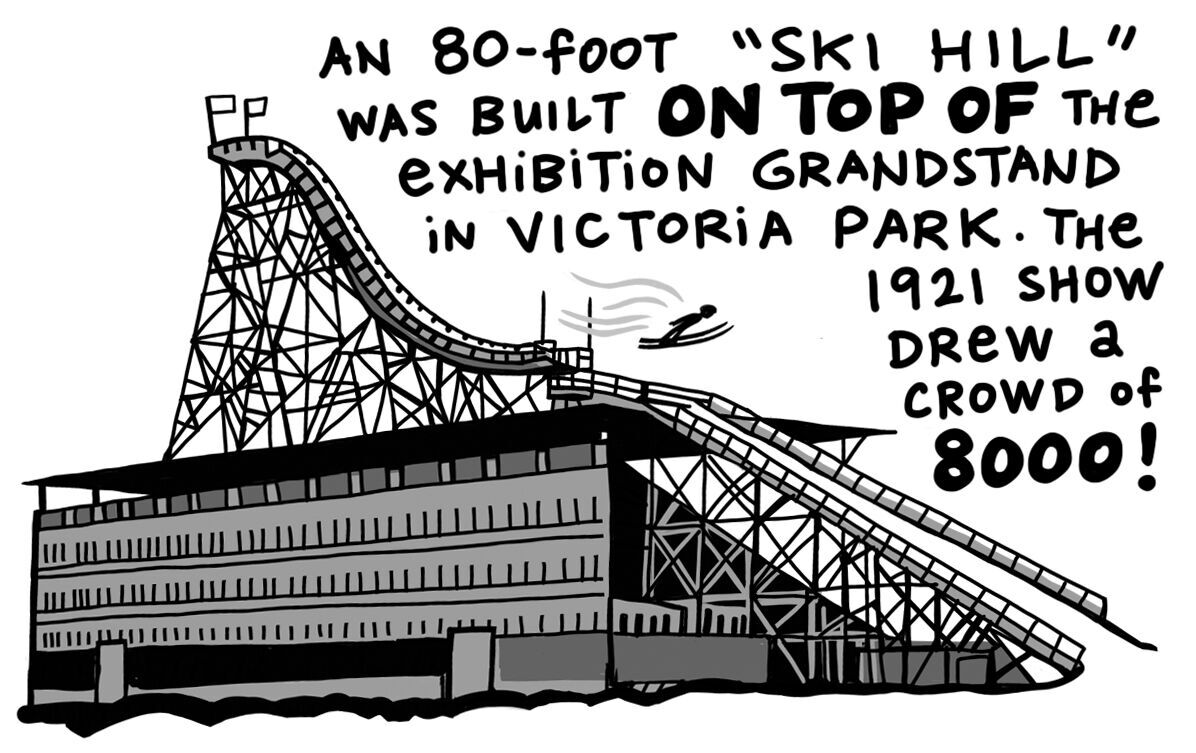

But the ski jump, built with steel shipped from Winnipeg, was the carnival's marquee attraction. Local newspapers couldn’t hype it enough. The Albertan called it the “most spectacular ski hill in the world.”

“A very fine structure,” declared the Herald on January 19, 1921. “It was erected at a heavy cost to the carnival committee but it is well constructed and will be a big asset to the city in years to come.”

At first, it seemed that way. Chinook winds were a concern from the outset but the Exhibition thought this could be dealt with through design. The jump was built facing east, so that skiers were taking flight in the same direction as the prevailing winds.

But Calgary's steep “ski hill” was rough going for the skiers, as it “had a tendency to shoot them like from a catapult,” the Herald later recalled. “Repeatedly the contestants would strike the slide and then lunge and topple head over heels down the incline to the ground below," reported the Herald on January 24, 1921.

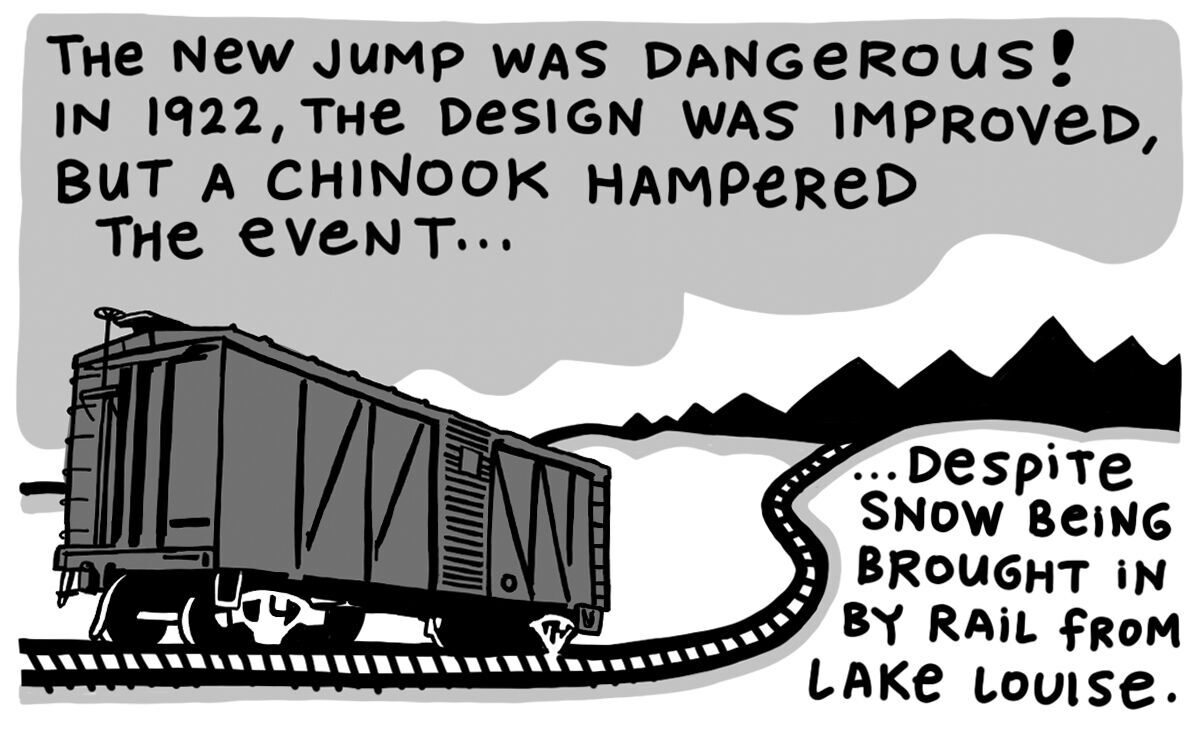

Alterations were required—small ones during the 1921 Winter Carnival, and more substantial ones before the 1922 event. For this E.L. Richardson took guidance from champion ski jumper Nels Nelsen, who immigrated to Revelstoke, B.C., from Norway.

Although the Calgary jump distances in 1921 “were not near the marks established at the big slides in the mountains, the people got a real taste of the sport,” reported the Herald.

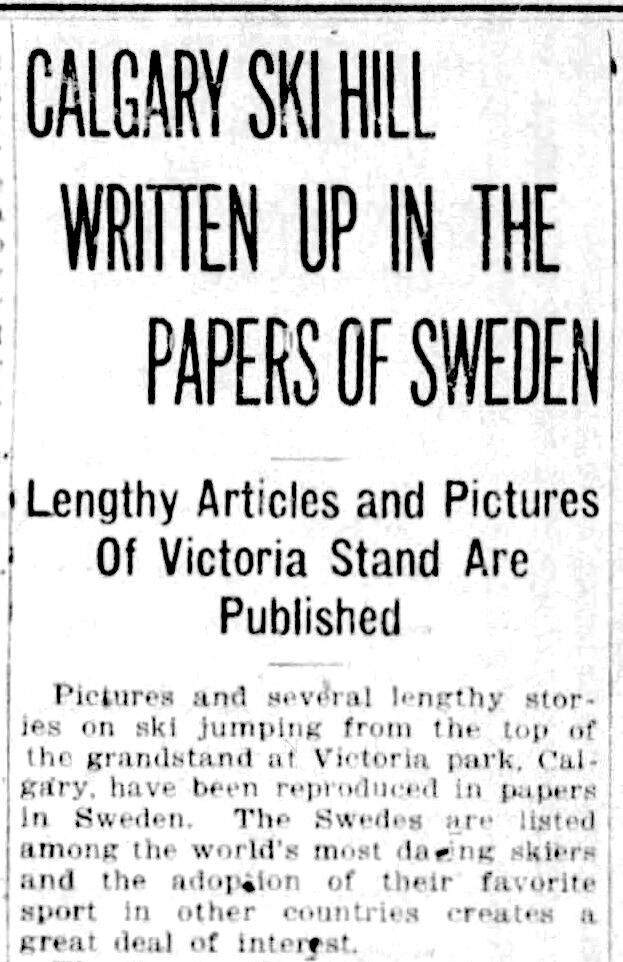

Calgary’s inner-city “ski hill” made headlines all over the U.S.: California, Wisconsin, Oklahoma. It even got press overseas.

A story that ran in numerous U.S. papers stated that Calgary's Exhibition grounds were “a perfectly ripping site for winter sports” and that “the furs and automobiles of these crowds were convincing evidence of the prosperity of these happy westerners.”

Hopes were high going into the 1922 Calgary Winter Carnival.

“No hitches will occur this season in the sport festival,” predicted the Herald. “Men who are thoroughly conversant with all the details of attractions will be placed in charge.”

But these men had no power over the main threat to the 1922 carnival: warm weather. It was the same threat that would afflict Calgary Olympics organizers more than six decades later, when warm chinook winds bore down on the Games in February 1988.

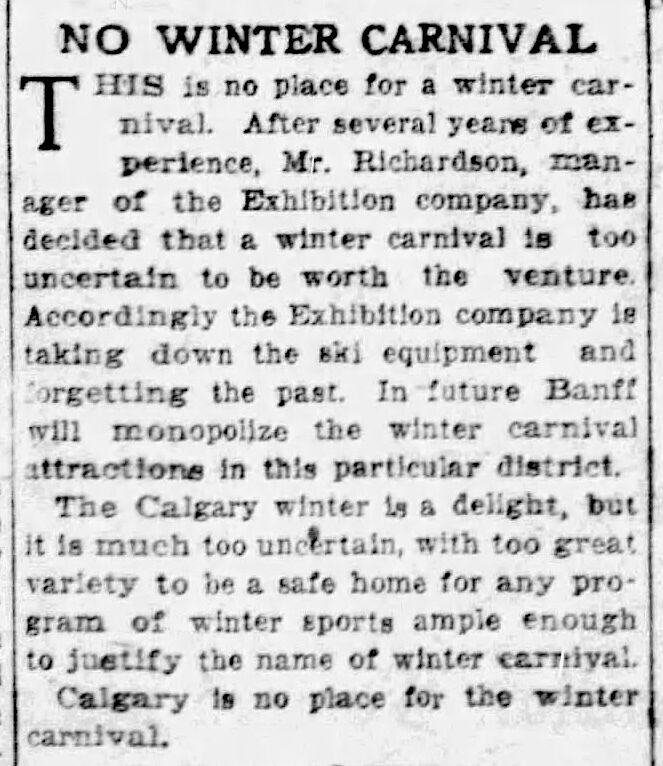

“The mild spell has upset all calculations,” noted the Herald on January 14, 1922.

The solution? Hauling snow to the ski jump—at first, from areas in and around town. “It is proposed to cart in a great deal of snow from different ravines in the district and this supply will be used to bank the hill,” reported the Herald. Then snow was hauled in from the mountains.

The show went on, despite the warm weather. “As far as a winter carnival is concerned, Calgary seems to be out of luck,” the Herald opined on the final day of the 1922 event. “The weather is not cold enough and there is not sufficient snow to make it worth while… as many have appropriately remarked, a winter golf tournament might be more in order.”

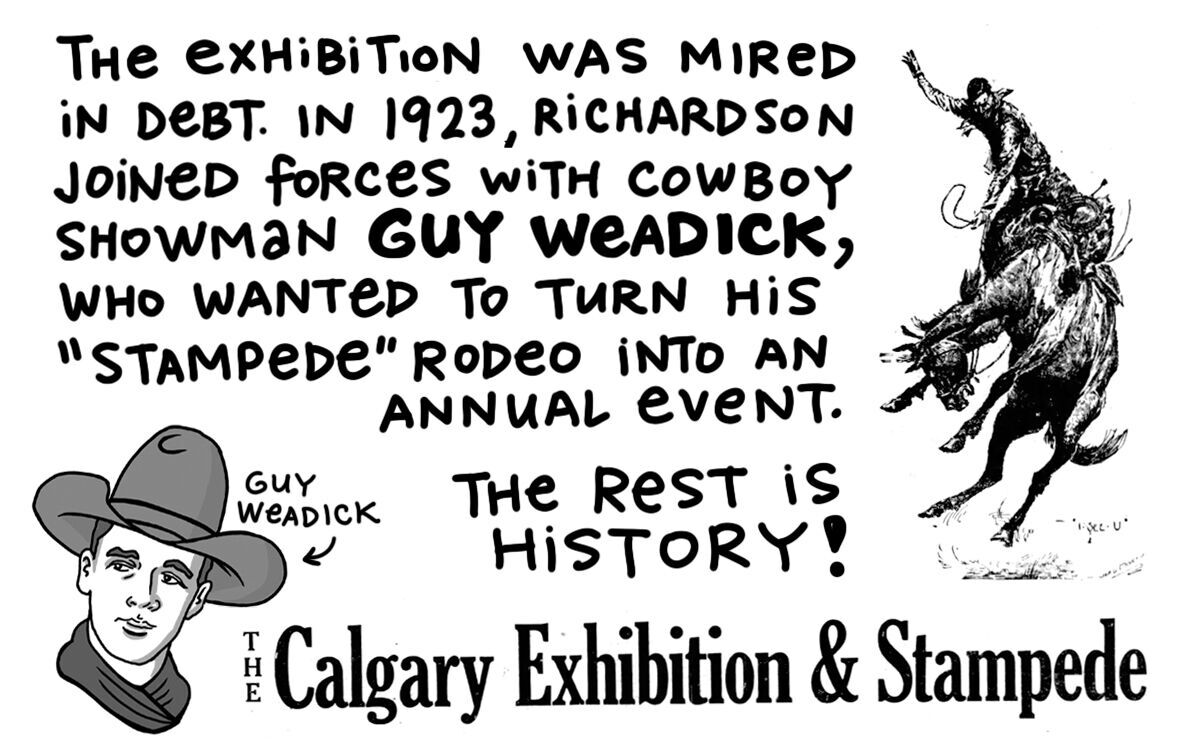

After the Exhibition and Stampede joined forces in 1923, they gave the winter carnival one more go in 1924. The newspapers went into it with their usual over-the-top boosterism. “Prospects are bright for one of the greatest community events that Calgary ever witnessed,” the Herald predicted on January 14, 1924.

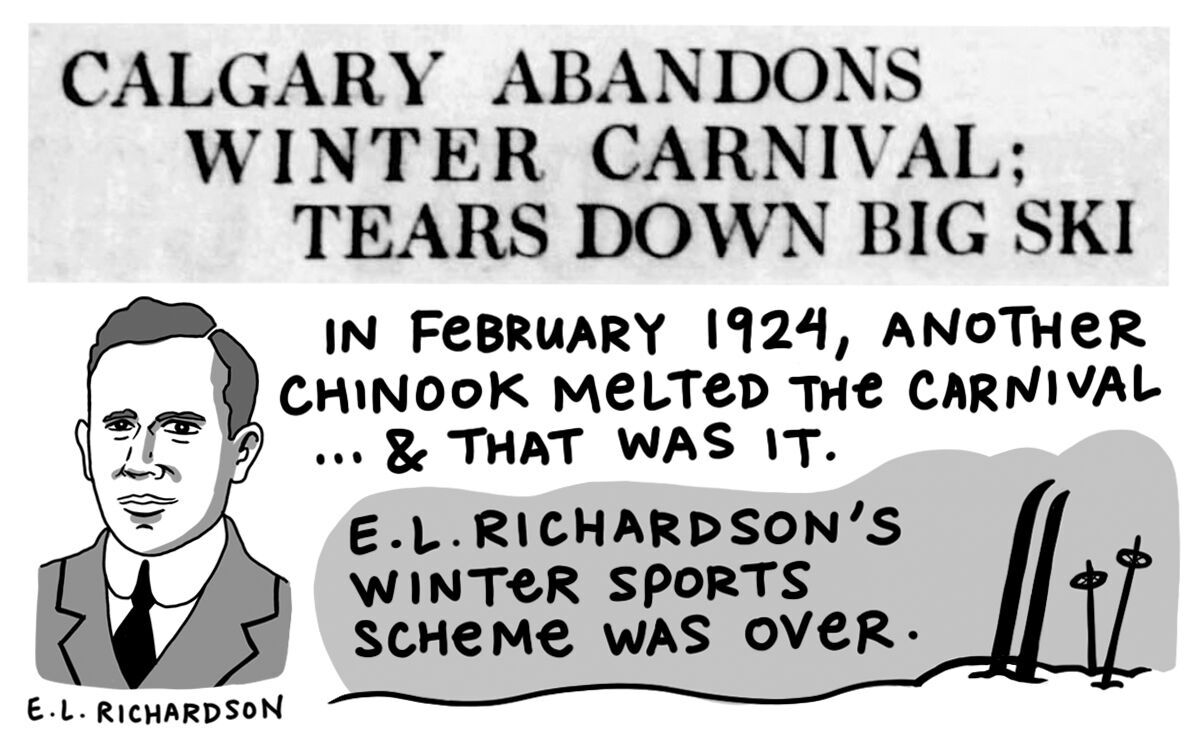

But the city was still prone to warm winter weather at the worst possible time. Temperatures reached 11 degrees Celsius.

An Albertan headline says it all: ALL CARNIVAL ICE EVENTS TODAY ARE CANCELLED.

In 1924, some 2,000 people showed up for the Saturday ski jumping—far less than in previous years. Skiers didn't fly far, either. The furthest went 77 feet, much less than the 110-plus feet that skiers were flying in 1921, when the jump was more of a death trap. “Distance not so good,” said the Herald.

When the Exhibition pulled the plug on the winter carnival in the spring of 1924, the newspapers approved.

“Now that the Winter Carnival is past it will be generally agreed that this city should not attempt to hold another,” stated the Herald. “...We might build an ice carnival one day only to have a Chinook reduce it to a running stream the next.”

“Another relic of Calgary of days gone by passes into history,” wrote the Albertan as the jump came down.

That was the end of the short-lived Calgary Winter Carnival—and the Stampede ski jump.

Jeremy Klaszus is founder and editor of The Sprawl. Sam Hester is a Calgary cartoonist and graphic recorder who writes The Sprawl's Curious Calgary series. Check out her Substack, The Drawing Book, for more of her autobiographical comics and stories!