Bridgeland Market, 2018. Photo: Jeremy Klaszus

The demise of local political Twitter

Can we re-humanize the conversation?

In his recent Maclean’s story on Calgary Mayor Naheed Nenshi, Jason Markusoff highlighted something that happened almost imperceptibly after the 2017 election: Nenshi stepped away from social media.

“The man renowned for his lively Twitter use—check often, comment often, joust often—has effectively unplugged,” writes Markusoff. “His @nenshi account is now as conventional and dull as any politician’s.”

What happened? I asked Nenshi last fall why he stopped being on Twitter. He answered succinctly.

“Because it’s horrible,” he said.

In 2020, few would disagree, including those of us who spend much of our lives on Twitter. The entire ecosystem has changed.

In 2009, when Nenshi was a Mount Royal professor agitating for tighter municipal campaign finance rules, social media held real promise. Those were innocent times—before Cambridge Analytica and Twitter pile-ons and the retweet button (whose creator, full of regret, has likened to handing a loaded gun to toddlers).

Doug Griffiths, a young Alberta MLA who’d become municipal affairs minister, could say with a straight face that Twitter was a modern equivalent of Socrates conversing with young citizens of Athens.

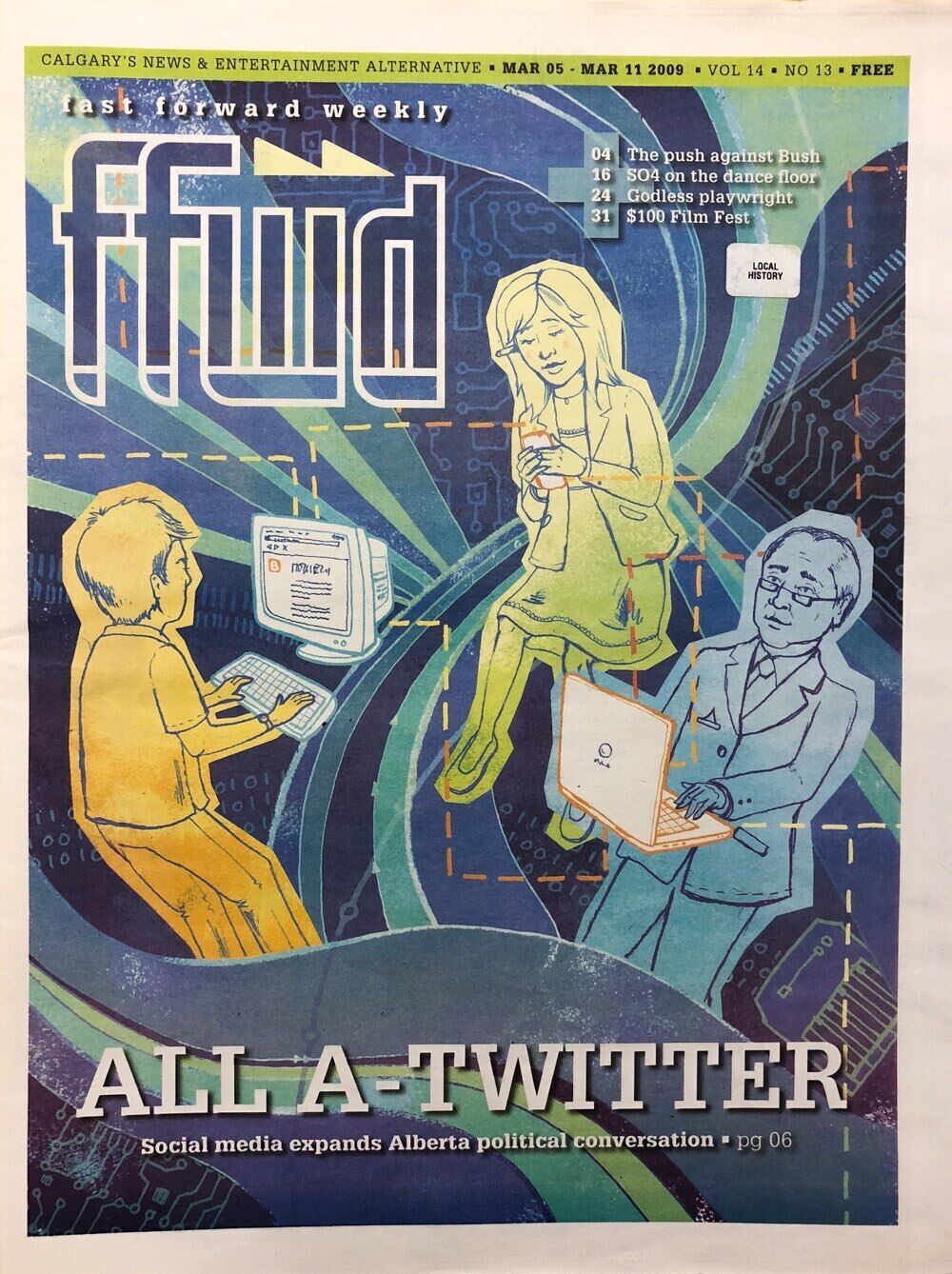

In 2009 I reported this in a FFWD cover story, which now seems laughably quaint, about how Twitter was changing political conversation for the better. I think of that story often.

"It actually crosses party lines," Griffiths said of Twitter conversations at the time. "You don't have PC versus Liberal versus New Democrat. You have discussions where partisan politics doesn't become involved."

Also in 2009, CivicCamp, the municipal advocacy group Nenshi co-founded, was using Google Groups and Twitter to organize for better public transit and constraints on urban sprawl.

“I think the atmosphere, when you look back at the late 2000s, was still really positive and optimistic,” recalled Jeremy Zhao, a Calgary engineer who ran for mayor as a university student in 2007 and was involved in CivicCamp. “Maybe almost to the point of being naïvely optimistic, but it was a good atmosphere to be in.”

“You could have a discussion with people and not be called out for stupid things. You could have an orderly conversation and agree to disagree, and then go out for a drink afterwards.”

Because of all the advertising and bots and hostility that’s arisen on Twitter, a lot of people avoid it.

One Calgary event from those days was #poliwings, a pub night that brought together people from different provincial parties. An annual bowling tournament did something similar while raising money for charity. At local “tweetups,” meanwhile, people gathered to meet the flesh-and-blood people behind Twitter avatars.

All of this humanized the conversation.

But over time, curiosity has largely given way to contempt. Social media is tuned for outrage and constant dunking—it’s all “engagement.” The most strident and partisan voices are rewarded.

“It's almost like its purpose is to get us to be polarized, get us to be agitated or frustrated about a certain thing, because that's how they get their clicks," said Zhao. "That's how they get their revenue.”

Many of the people who were involved in Calgary politics in that era have, like Nenshi, logged off.

“Now you only attract really dedicated people to Twitter,” said Kate Easton, one of Nenshi’s handlers in the 2010 election. “Because of all the advertising and bots and hostility that's arisen on Twitter, a lot of people avoid it. And so I think that makes the kind of discussion that's being had on there perhaps more polarized—because you've really only got very strong-minded people on there now.”

Easton recalls that during the 2010 campaign, she spent “all day” on Twitter. Now she barely goes on. Same goes for Zhao.

I think the atmosphere, when you look back at the late 2000s, was still really positive and optimistic.

And Nenshi? In 2016, the New York Times reported glowingly about how “A Mayor Fluent in Twitter Embodies a New Canadian Diversity.” But as Markusoff recounts, the 2017 election changed that. His team was inundated with racial slurs online, and it took a toll.

Zain Velji, who managed Nenshi’s 2017 campaign, recalls breaking down in tears at one point because of all the online hate—and it wasn’t even directed at him.

“I can't imagine how he dealt with it not just during that high-water mark of the campaign where it was notably aggressive, but has to deal with it on this weird, mid-level burn all the time,” said Velji. “It takes a toll on how you process what you do, it takes a toll on how you interact with your colleagues and I think it takes a toll on your mental health.”

Velji, too, is Twittered out.

“What breaks through in a 2019 social media world is not what broke through in a 2010 social media world,” he said. “It's not calm, deliberative thoughtfulness. What breaks through in 2019, considering everyone has an account and there's so much noise, is hot takes. It's choosing something that pierces through because it's either provocative or aggressive or angry or fear-and-loathing.”

“You reward that as currency on social media—well, dammit, that changes behaviour over a decade, doesn't it?”

What breaks through in 2019, considering everyone has an account and there’s so much noise, is hot takes.

Nenshi isn’t the only candidate from Calgary’s 2010 election who is weary of it all. Barb Higgins, the former CTV Calgary anchor who ran against Nenshi, is likewise dismayed by dehumanizing comments she sees on social media—on Facebook, specifically—and what this means for civic life.

“I think it's just become even meaner,” said Higgins, who, after the 2010 election, went on to become a counsellor and public speaker.

“I think it's become that the general public thinks that it is okay to be completely abusive to candidates. And I think when I was running, it was basically people who were in other camps that were doing it—but now I think it's the general population that thinks it's okay.”

The next Calgary election is in 2021. Before then, can we recover a sense of—I don’t want to say civility, because that suggests mere politeness, but civic mutuality? Something more than constant derision for each other?

Can we be better than this?

I think it’s become that the general public thinks that it is okay to be completely abusive to candidates.

Social media platforms are rigged against it. But Higgins offers a helpful insight. On social media, we tend to think it’s other people who are endlessly posturing, insufferable and just plain wrong.

But maybe those people aren’t so much the problem; we are.

“We can blame the parties, we can blame corporations, but really it's who we're looking at in the mirror,” said Higgins.

“We can all get caught up in the heat of the moment, but we all need to be able to back up sometimes and say, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa.’ It's okay to go, ‘Is that really the way I want to behave? Is that really the example I want to set?’ And we need to get back to that.”

In the meantime, I keep thinking of a recent conversation with a friend. He’s realizing that taking a quiet morning walk is a better way to be a truly engaged citizen than scanning social media for the latest conflagration.

Wise words.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

The Sprawl is crowdfunded, ad-free and made in Calgary. Become a Sprawl member today to support independent local journalism!

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!