Illustration: Julien Genereux

It’s time to end predator culture for good

Today’s students are fighting back — and I envy them.

Note to readers: This essay discusses sexual assault.

When I first read about how the sexual assault allegations against Calgary city councillor Sean Chu were handled, I wasn’t surprised.

Learning that a 16-year-old girl had accused him of violent sexual assault during his time as a police officer—and that he received a slap on the wrist by way of a letter of reprimand after a disciplinary investigation—made me angry but didn’t shock me. The fact that even the province says it is powerless to remove a city councillor from office served to remind me that we still live in a place that protects its old boys.

At a time when our youth are standing up to be heard on issues of sexual assaults in schools, our institutions are maintaining a status quo that rewards predators and punishes prey.

I also had a notable experience with the Calgary Police Service in 1997, the year Constable Chu allegedly preyed on a teenage girl.

After a difficult relationship, it had been suggested to me that I obtain a restraining order against a former partner, someone who had begun stalking me. I was scared, living alone and trying to break ties with an individual I no longer wanted in my life. At one point, this person breached the order, approaching me. When dialogue didn’t resolve the situation, I called the police to report the breach.

Two male police officers showed up at my apartment to take my statement.

One was clearly a senior member of the Calgary Police Service, taking charge and coaching the other officer, a rookie. They listened and took notes. They told me to surround myself with friends, and then they left.

In the years that followed, I’ve thought about this incident many times.

Half an hour later, I received a phone call. It was the older cop. He asked if I was busy later that evening, as he and his partner would be off shift. He said they would like to take me to Cowboys nightclub for a drink. I tried to find words but stumbled over an explanation that I was busy with school and that Cowboys wasn’t really my scene.

After hanging up the phone, I looked in the mirror. Had I given off some kind of vibe? Were my paint-splattered art school coveralls and messy ponytail sending a message? What had I done to attract this kind of attention from two police officers? After some reflection, my thoughts shifted to wondering what kind of cops would ask a young woman out to a bar after taking her statement regarding a breached restraining order.

In the years that followed, I’ve thought about this incident many times.

I’ve considered the fact that the older cop called on behalf of the rookie, trying to set us up. I’ve thought about how the seasoned officer coached the newbie when he took my statement, and how he also taught the rookie how to prey on a vulnerable young woman. This was clearly a culture.

Granted, they couldn’t have known that in my twenty-some years growing up in Calgary, I had been the victim of childhood sexual abuse, an obscene caller, a man who had followed me home from elementary school and tried to break into my house, teenage sexual assault, and years of catcalling, unwanted touching, and predatory gaslighting.

They couldn’t have known those details about me, but they should have. As far as early predatory sexual experiences go, I am far from alone.

The need for these truths to be told

There are legions of us trying to pick up the pieces of our lives and hold them together while shame, guilt, fear, and anger rage through us. We mourn the loss of our innocence, the adults we could have become, free of the baggage that comes with survivorhood, the landmines that are triggered just when we think we’re getting on with our lives.

We do whatever it takes to avoid going back to those places where we lost our trust.

We drink too much, eat too much, exercise obsessively, lay paralyzed with depression and seek out what we know, what feels familiar, which is often what we shouldn’t have known in the first place—abuse, manipulation and dysfunction.

Our spirits are shaken, while theirs are barely stirred.

Of the girls I grew up with, few were spared the weight of experience with sexual aggression. Today, when discussion comes up around this topic, a handful of adults I know comment that they feel lucky to have come this far unscathed, lucky not to have been victimized.

Think about that: lucky to have escaped the people and institutions that allow this to go on and on and on. Like the church organization that sat silent as my friend was sexually abused and exploited by known Calgary pedophile John Wrenshall, who led a scout troupe, youth group and choir—and was allowed to continue working with boys, despite a conviction involving the abuse and exploitation of children.

My friend fought for years to be seen and heard by a religious organization that condoned this abuse by remaining silent, to receive acknowledgment and reconciliation for the harm that has plagued him in his relationships, his career and his ability to move forward, to survive. In therapy, he has been told that his trauma will be lifelong, that he will need to learn to walk beside it.

Like a terminal disease, there is no cure.

These assaults are first sexual experiences for many. They go on to see subsequent moments of intimacy through a lens of trauma. The unacknowledged truth lingers and eats away at our self-esteem, self-confidence and self-image. It is the gaslighting that freezes us into self-doubt—it wasn’t that bad, that’s not how (the accused) remembers it, you have a vivid imagination, a selective memory, no one will believe you.

Why tell your story if your words will be met with disbelief, humiliation and scorn?

The need for these truths to be told and for predator culture to be refused is at the core of healing the injured company I find myself with.

As survivors, we try to make it all more palatable, to turn victimhood into something less shameful and horrifying. Sometimes it’s to spare the ones we love, to keep the truth hidden so that we can at least save someone from the pain. All the while, the truth that keeps us up at night, that finds us crying in the bathroom at work or hiding in our closets at home to keep the fallout from our families is this: The perpetrators get to go on living their lives, unburdened by the trauma. They get to trust.

Our spirits are shaken, while theirs are barely stirred.

The bravery of today's students

Kids who have been abused scramble to find the tools to stand up for themselves. They struggle to have a voice because they have been scared into staying silent by someone they trusted, someone who was supposed to take care of them. They often move forward into adulthood ingrained with this uncertainty.

Why tell your story if your words will be met with disbelief, humiliation and scorn? Having a voice means being credible, and history has shown us that victims of sexual assault and abuse are notoriously scrutinized and forced to prove themselves worthy of belief. This is how pre-emptive silencing has come to be the norm. This is why so many sexual assaults go unreported for so long.

We allow the narrative to be controlled by systems that take survivors of sexual predation and keep their unsavoury stories at a low whisper, until so many stories surface, they are impossible to ignore. Institutions like the NHL refuse to acknowledge their complicity in a culture that protects perpetrators until the victims add up and they can no longer deny the problem. Even then, blame is passed off and institutions are spared at the expense of victims and their future mental health.

My generation, GenXers, are part of that last group of children to believe we are better seen and not heard, to be quiet and sit still, to go forth into the world respecting our elders simply because they are older and more powerful than we are.

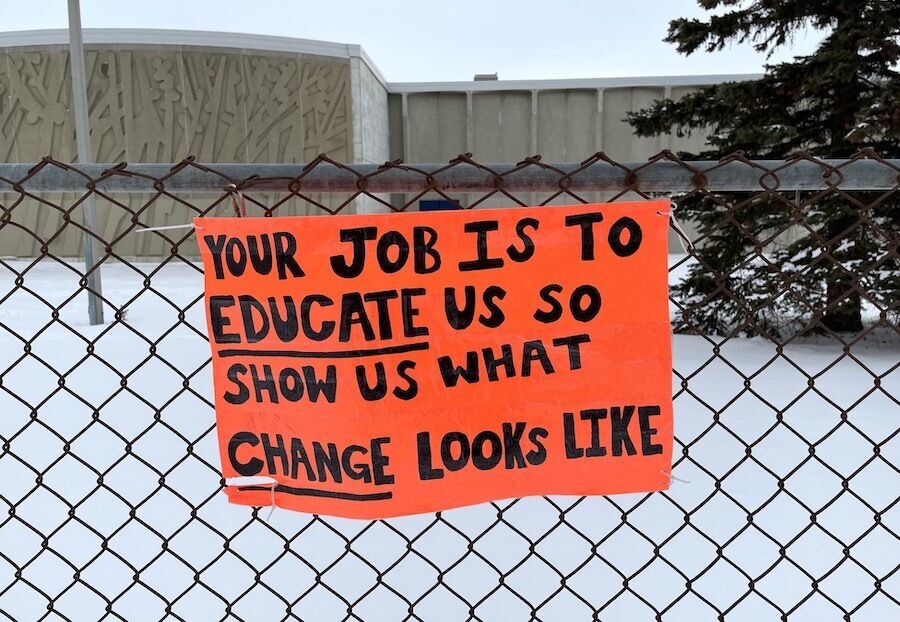

This past November, when groups of brave high school students began a series of walkouts from Calgary high schools to protest the inaction of the Calgary Board of Education with regard to reports of sexual harassment and assault, I envied them. I wished I had been as bold and wise as these warriors. I first heard about the story through my eldest son, a student at one of the schools. I watched the organization taking place over social media. Later that night, I turned on the news, eager to see change.

I saw kids demanding to be heard and feel safe. I saw young people advocating for a process that spares them the burden of injustice that allows predators to move forward and prey to stand still in their pain.

Are we going to continue reducing these voices to whispers by way of apathy, indifference and denial? Is the talent pool so small that we must employ sexual predators in positions of power?

We can do better. There are so many qualified and decent people in this city. It’s 2022. Let’s trust them instead.

Special thanks to Ben Howell for his very personal insight into trauma and healing. If you or someone you know has been affected by sexual assault, there is help in Calgary. Check out Calgary Communities Against Sexual Assault or the Calgary Police Service resources for sexual assault.

Heidi Klaassen is a born-and-raised Calgary writer of fiction and non-fiction. She works for the Alexandra Writers’ Centre Society and her eco-friendly label, Hekkal & Hyde. She lives in Calgary with her husband, sons and rescue chihuahuas.