Photo: Jeremy Klaszus

Just cut taxes? If only it was so simple

A sprawling city has immense costs.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!

When Tamara Lee and her husband Danny purchased their Sunnyside home in the late 1980s, the neighbourhood wasn’t the desirable community it is today.

“It was kind of shabby,” Lee recalled. “We had cracks in our sidewalks, streetlights would go out and wouldn’t be repaired. It was starting to feel a little dire.”

But the last decade has brought about dramatic change to Sunnyside.

The Lees have seen the construction of the Peace Bridge, Poppy Plaza and the downtown cycle-track network, along with the introduction of recycling and composting. All of these have added to the Lees’ quality of life.

The improvements were in part made possible by the property taxes Calgarians pay each year. For Lee, having her taxes double in three decades has been worth it. “It was wonderful to raise our daughter in the same neighbourhood I grew up in,” she said. “And we’re willing to have our taxes pay for that.”

Research shows that property taxes are the most effective way to fund public services because they are relatively fair, stable and support the self-reliance of cities while holding their governments accountable.

Six years after a crash in oil prices triggered a recession in Calgary, and in the midst of a global pandemic, many cash-strapped Calgarians are understandably concerned about their ability to make ends meet and avoid unnecessary expenses. But despite the reductionist claims of some election candidates, tax cuts aren’t a panacea.

Over the past four years, city council has spent more than $200 million on a series of tax rebates for businesses facing sharp increases due to vacancies downtown.

“We’re getting down to the real core here,” said Lindsay Tedds, associate professor of economics and scientific director of fiscal and economic policy at the University of Calgary.

“And when we’re getting down to that level, it means we’re actually cutting from services that maybe high-income individuals don’t use. But we don’t run a city on high-income individuals—we run a city on everybody.”

The cost of running a city of 1.4M people

“Albertans actually care about services, and the quality of services—they just don’t want to pay for them,” Tedds said. According to the city’s latest citizen satisfaction survey, two in five Calgarians oppose a property tax increase, even if it means cuts to existing services.

But a majority continues to value the amenities and services that taxes afford us. According to the same survey, around three in five Calgarians think they receive good value for their property tax dollars.

According to Sustainable Calgary’s State of Our City report, led by Noel Keough, publicly-funded amenities and services such as parks, libraries, and waste management have contributed to Calgarians’ wellbeing and the city’s long-term sustainability—despite an overall downward trend fuelled by urban sprawl.

We don’t run a city on high-income individuals — we run a city on everybody.

The implications of sprawl go well beyond our city’s ability to meet sustainability goals. Sprawl is also linked to our property taxes and the growing costs of maintaining our city.

“When we’re building a new community, we have to assess what is the ability of that new community to pay for itself,” Tedds said. “And very rarely a new community pays for itself because that infrastructure is expensive to build and expensive to maintain.”

“This is why we see the redistribution of tax revenues from the inner-city to the suburbs.”

As a result, some inner-city communities remain underserved, despite having higher property values and therefore paying more in taxes. “Who really should be paying that, is a fundamental question we should be asking,” Tedds said.

Recognizing that our taxes are already relatively low, some Calgarians are also concerned about our ability to maintain the aging infrastructure of a sprawling city with a high standard of living.

“Can we afford what we have?” wondered Nathan Hawryluk, a Calgarian whose curious nature led him to calculate how much the City of Calgary should be collecting in taxes.

He found that in order to maintain Calgary's infrastructure, the city would need to collect $2.98 billion (in 2017 dollars) every year—"good, bad or pandemic-filled"—forever.

“To get that, the city would need to more than double its residential taxes,” he wrote in an article in Strong Towns earlier this year.

Very rarely a new community pays for itself because that infrastructure is expensive to build and expensive to maintain.

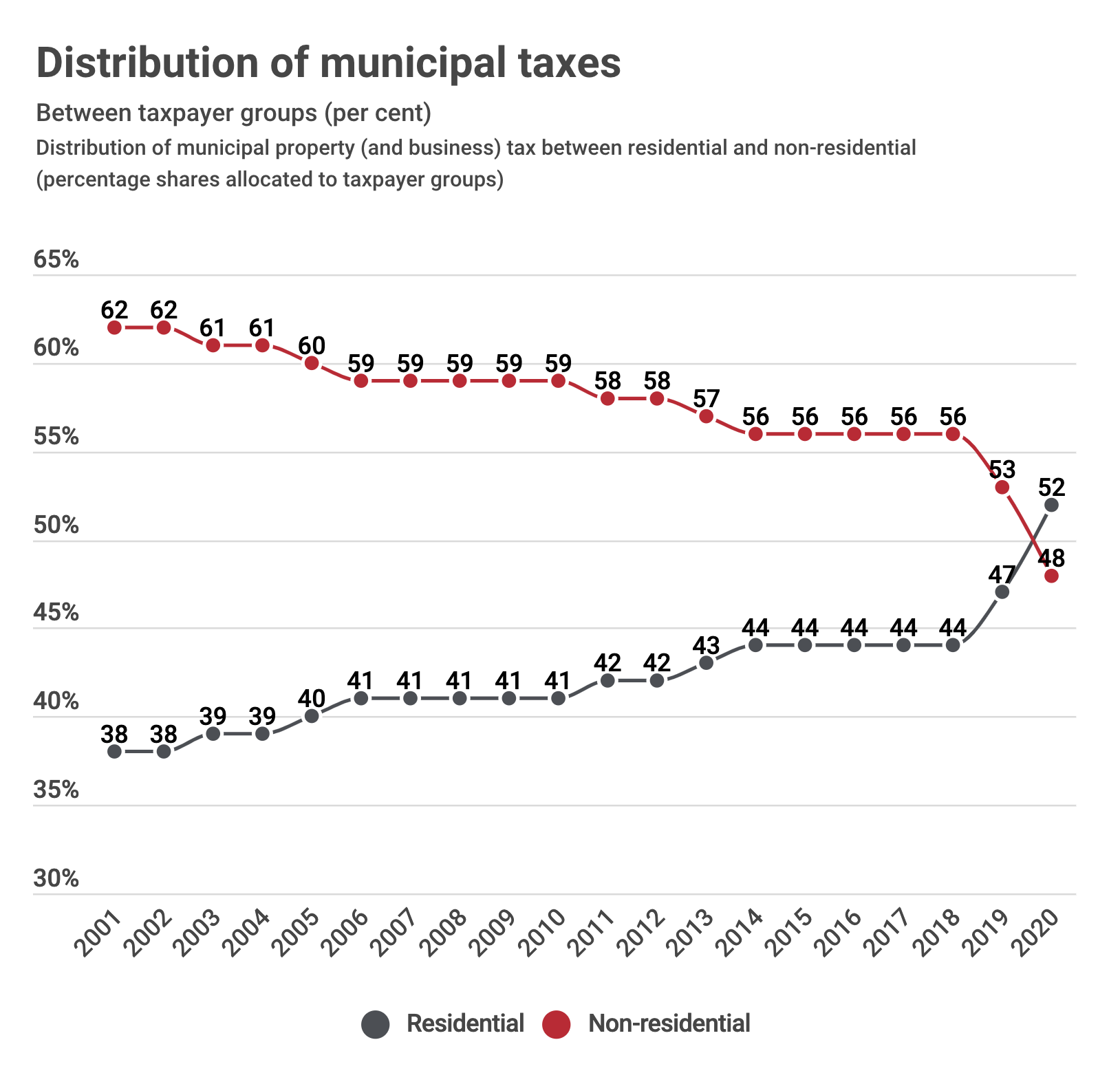

In order to afford a lower tax rate despite rising costs, Calgary already charges user fees and levies on a number of services. But this is not enough. Calgary relies heavily on non-residential property taxes paid by businesses, which have historically accounted for most of the city's tax revenue.

After the economic downturn gutted our city’s core and non-residential property taxes cratered, this is no longer sustainable.

“Because the City of Calgary pegs the proportion of revenues, this leads to an incredible amount of volatility in the non-residential sector,” Tedds explained. “As soon as valuation drops, mill rates go up. And it has to go up for no other reason than just because revenue is down.”

City council has started dealing with this through a "tax shift," incrementally shifting more of the tax burden from businesses onto residential ratepayers. In 2020, for the first time, residential property taxes accounted for more than half (52%) of the city's taxes.

But while property taxes are the largest revenue source for Canadian cities, they’re not the only potential source of revenue.

Finding alternative sources of revenue

“There's lots of ways that cities can change their revenue sources,” said David Thompson, an economist, researcher and co-founder of B.C. consulting firm PolicyLink.

These possibilities include making property taxes, land transfer taxes, and user fees more progressive, along with adding new revenue streams.

For this reason, the city put together a financial task force in 2019 to identify revenue alternatives such as additional user fees, levies and new taxes.

Little has been said, however, about the nuances of these options since the task force presented their recommendations to council in June of 2020.

According to Tedds, who was on the financial task force, an additional revenue source the city has underused is development charges.

“I think that has a lot to do with the power of developers here,” she said. “The only reason why [suburban communities] are being approved is to keep developers happy.”

There’s lots of ways that cities can change their revenue sources.

Charging developers for building an increasingly unsustainable city is not the only way to increase revenues and alleviate some of the pressures non-residential property taxes put on businesses.

Creating additional property tax classes and sub-classes is another strategy that other provinces already implement.

In Ontario, for instance, different types of residential and commercial properties pay a different rate. This approach, according to Thompson, “makes taxes more progressive,” a feature that transforms property taxes into a mechanism for local wealth redistribution, rather than only paying for public services and infrastructure, and also addresses inequality.

Inequality, Thompson notes, “is associated with all sorts of negative social outcomes ranging from higher rates of violence to teenage pregnancies to diabetes and mental illness.”

If large cities got together and lobbied the government to do something more about inequity, inequality, and income, that could make a huge difference — and could lower taxes.

And addressing the consequences of inequality can be costly for other levels of government, such as the provincial government, which pays for health costs.

“If large cities got together and lobbied the government to do something more about inequity, inequality, and income, that could make a huge difference—and could lower taxes,” said Noel Keough of Sustainable Calgary. “Because the [primary] reason we need social programs is that we pay people inequitably.”

In a city looking to attract more tech—an industry that’s already wreaking havoc for lower-income residents in “world-class” cities such as Austin and San Francisco—decision-makers should consider alternatives that address inequality before it happens.

“Many of the new tech economy cities are very unequal,” Keough noted. “[Tech] may be worse than the oil and gas industry in terms of the gap between rich and poor and disparities.”

Currently, just over 2% of the property taxes Calgarians pay fund social services.

A better way to think about taxes

As we get closer to election day on October 18, rather than attempting to choose the lesser of two evils—tax cuts vs. service cuts—Tedds suggests Calgarians should ask themselves, “What kind of city do you want to live in?”

For Brett Bergie and her family, property taxes have enabled them to live a more sustainable lifestyle and reduce their expenses. Living in a small condo in East Village, they enjoy nearby public amenities such as parks and libraries as an extension of their own home.

I can’t go out and build a Green Line as an individual, but as a community we can.

Living in a service-rich, central location allows them to embrace public transit and active transportation modes—and entirely forego car ownership. “The pathway network, as well as the cycle tracks and just bike lanes in general [are] critical for me to access the city,” she said.

Cognizant of how taxes support her values, Bergie notes that “when we consider the climate crisis and the solutions that are required, I can’t go out and build a Green Line as an individual, but as a community we can.”

And this collective way of thinking is precisely why we pay taxes to begin with.

“The reason why we live in society is to overcome problems of an individual having to do everything on their own,” Tedds said. “When we form ourselves into society, we can all do better. And that’s how we should be thinking about taxes.”

Ximena González is a freelance writer and editor. Her work has appeared in The Globe and Mail, The Tyee and Jacobin.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!