Henry Wise Wood was an important agrarian leader in Alberta. Photo illustration: Hamdi Issawi

Slavery and the making of Alberta

The evidence of things not seen.

In 1964, a section of the Salt River in Northeastern Missouri was dammed and a new lake was birthed.

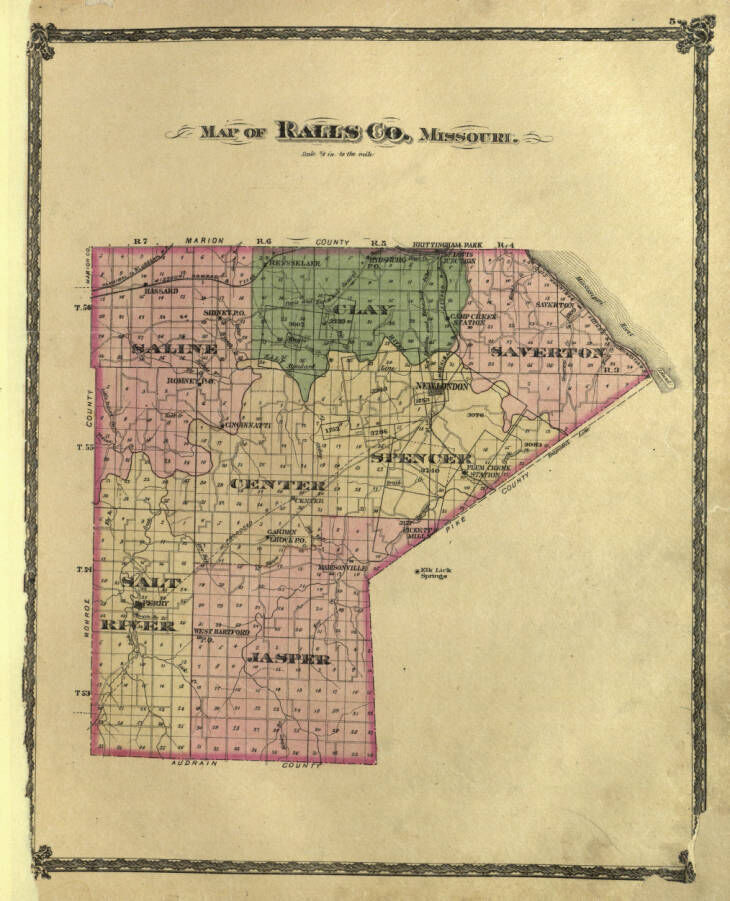

The lake is amoeba-shaped, complete with pseudopods sprawling across both Ralls and Monroe counties. The small town of Florida, in Monroe County, once bordered the river but is now almost entirely surrounded by the lake. You may have heard of this town. You have probably even read about this corner of Missouri and the famous Mississippi River, which rolls its ponderous way southward only 30 miles from this new lake.

The lake’s name is Mark Twain Lake.

The famous author was born in the town of Florida and grew up in the region. His depictions of steamboats on the Mississippi River, the boyhood antics of Huck and Tom, and the loyal, formerly enslaved Jim, are all so emblematic of antebellum America that even we, here in Alberta, find them familiar.

Actually, for reasons that will become clear, I’d rather not focus on Mark Twain. You may suspect me of wanting to eject Twain in accordance with the current spirit of tearing down statues and reconsidering how men of a certain era are memorialized.

As a Black reader, I admit I was never fond of what often appeared as an indulgence of a certain racial slur in Twain’s writings. Indeed, another writer, James Baldwin, might have agreed with my stance. Among other things, the great African American intellectual never saw the dramatic value in Huckleberry Finn’s “moral predicament” concerning whether or not Jim should be sold back into slavery. Me neither. But there is something more important I would like to draw your attention to. So, for now, let’s move on from Twain.

Let’s shift instead a few miles north into adjoining Ralls County, where a dramatic scene took place during the Civil War on a small farm Twain may have encountered but certainly never wrote about.

The farm, nestled near Saline Township, was owned by John Oliver Wood, a Confederate sympathizer.

Wood’s sympathies allegedly did not sit well with his neighbours. Missouri was a patchwork of complex loyalties during the war, with different parts of the state holding opposing views. Arguably, the state itself sat on the fault line of divided loyalties: the Missouri Compromise was an attempt to placate both abolitionists and proponents of slavery alike. It failed and, ultimately, the Civil War ensued.

The Wood family would have a profound impact on the province of Alberta.

One fateful night, according to Wood family lore, vigilante neighbours came looking for John when they learned he had returned from battle to visit his family. Their mission was thwarted by two people who steadfastly refused to divulge his whereabouts, despite one of them suffering physical violence as a result.

These people, Warrick Duncan and Tilly (known by the family as “Old Till”) were enslaved African Americans who worked the farm. This story is meant to demonstrate the deep loyalty the slaves showed and therefore the affinity they had for the Wood family, a branch of which would have a profound impact on the province of Alberta.

Henry Wise Wood—born into a pro-slavery family

John Oliver Wood’s Confederate sympathies are unsurprising.

He came to Missouri from South Carolina. Before that, his father, James, had come from Virginia and had also counted enslaved Africans among his possessions. The family retained their southern sensibilities when they moved to Missouri and may have brought enslaved people with them as well (like James Wood, Warrick Duncan was born in Virginia).

In 1860, a time fraught with the build-up to the Civil War, John Oliver Wood gave a nod to his southern roots by naming his fifth child after the pro-slavery, secessionist Governor of Virginia: Henry Alexander Wise.

This child, like Mark Twain over in the next county, became famous.

Unlike Twain, Henry Wise Wood never had to publicly grapple with the legacy of slavery in his life.

Unlike Twain, though, his fame is mainly restricted to western Canadian history and specifically Alberta. And, also unlike the famous writer, he never had to publicly grapple with the legacy of slavery in his life.

Somewhere between the anonymity of Till’s and Duncan Warrick’s forgotten lives and Mark Twain’s supernal celebrity lies Henry Wise Wood’s modest fame. Yet, most people who have learned about the agrarian movement in Canada or the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) or the history of wheat pools know the name Henry Wise Wood.

In photos, he looks an unlikely leader. He has soft, kindly eyes; his forehead is ponderous, extending from a prematurely bald head; his whole face, both boyish and headmasterly, emerges tentatively from a diminutive chin and small jaw.

Yet he had a magnetic personality and was highly regarded. He was something of a farmer's philosopher: unprepossessing, principled, and thoughtful, but equally pragmatic and straightforward.

At a time when 70% of the province’s population lived off the land, he settled right in, presiding over the UFA and the Alberta Wheat Pool, managing a farm in Carstairs and tending a personal garden in his free time. He was a skilled and influential orator.

Had it not been for his strong belief in farmers self-organizing over political involvement, he would have certainly filled the premier’s role when the UFA governed the province from 1921 to 1935.

As one of the architects of Alberta’s Wheat Pool and Farm Association, Henry Wise Wood is partially responsible for our contemporary sense of the Albertan identity. We remember grain elevators and we recognize agriculture—even us city-dwellers—as part of the province’s basic DNA because of his influence.

He is a central figure in Alberta’s development, but few people are aware of his southern origins or of the slave-holding tradition that forms a part of his family’s story.

The lives of Warrick Duncan and ‘Old Till’

Warrick Duncan and “Old Till,” two of the enslaved people who laboured on the Wood family farm, made enough of an impression on Henry Wise Wood that they are mentioned in his archived papers. But very little is known about either of them.

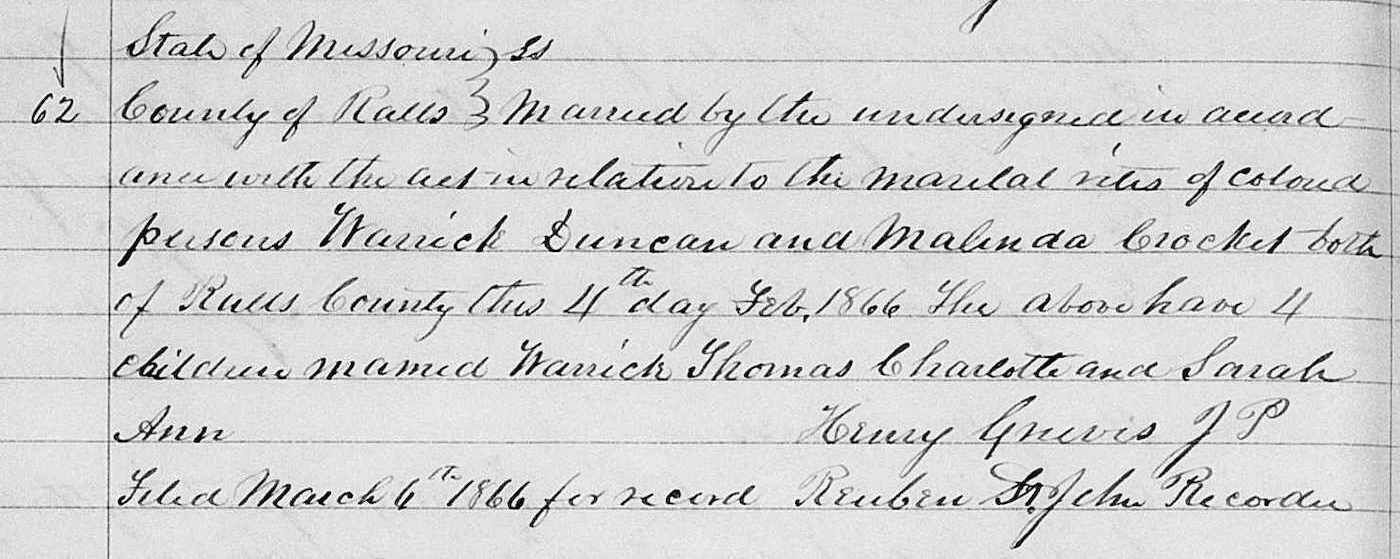

Out of sheer fortune, Duncan shows up in two sets of documents, so more is known about him. He was born in 1817 and had a wife, Balinda (or Malinda), and at least three children, including Thomas, Charlotta, and Lucy Jane (or Sarah Jane). After the Civil War, he settled with his family in Monroe City, a town very near to the farm he was once enslaved upon.

One striking and poignant fact stands out about the family. On February 4, 1866, Warrick and Balinda were officially married and the entire family was baptized. All on the same day. Think of it: Barely a year after the war ends, slavery is abolished and this family almost immediately takes the opportunity to commit to each other and to their faith by embracing an official status that was previously denied them.

What a jubilant day it must have been for them.

Not so for Till. That is, we cannot know for her. Her personhood has been lost to us.

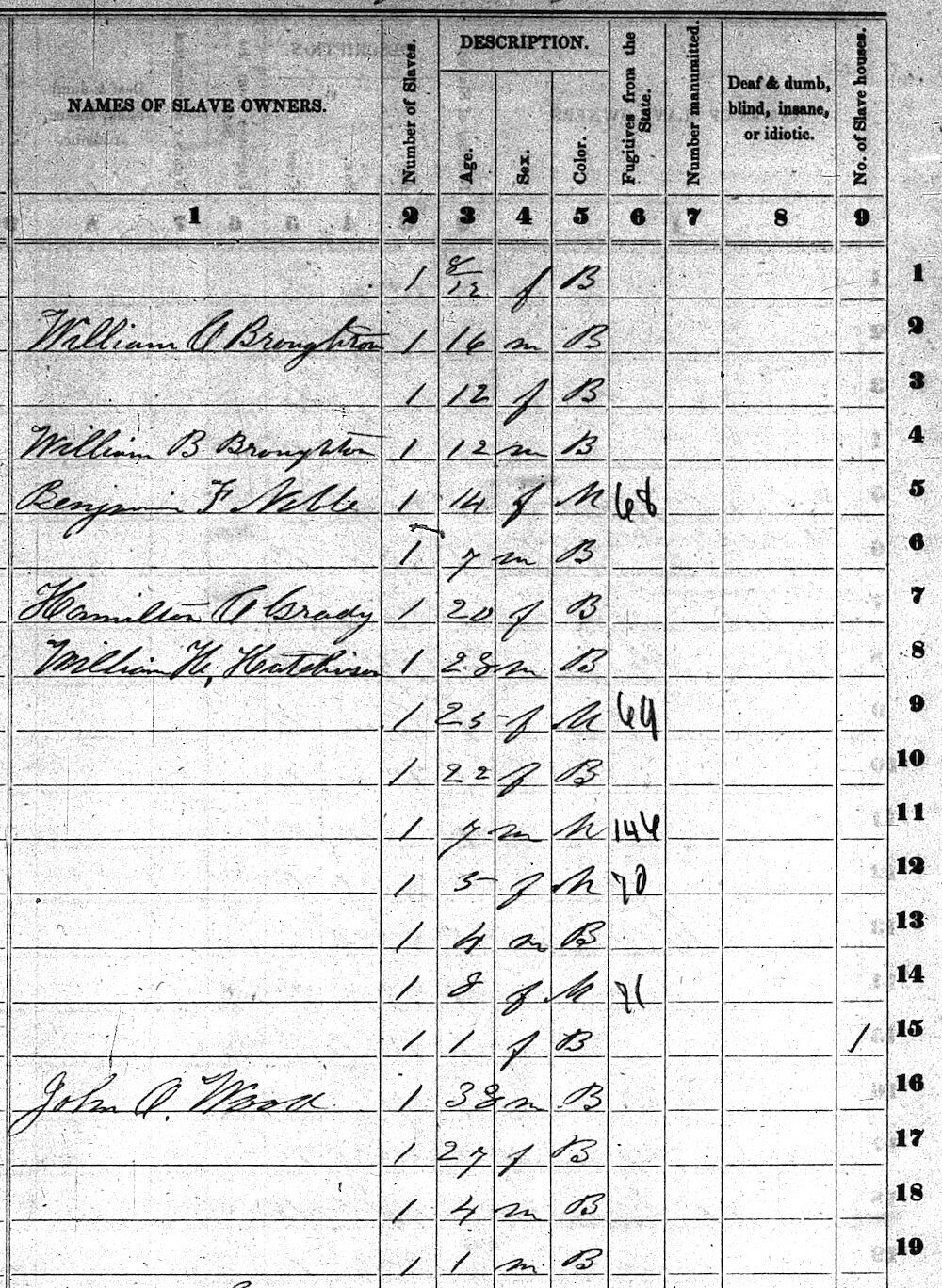

The only official document she might have been on with certainty is a slave schedule. But slave schedules focus on the owners’ wealth. We can know that Henry’s grandfather, father, and an uncle enslaved nearly 30 people between them in 1860, but we can’t know who those enslaved Africans were.

Though counted on slave schedules, enslaved people are almost never named.

We know of “Old Till” only because of what Henry Wise Wood chose to include in his account. What he chose to exclude from Till’s story, though, is nothing short of a tragedy. According to the family narrative, Till was strung up three times but still refused to divulge John Oliver Wood’s whereabouts.

The purpose of this story, as related by Wood (as well as his biographer, William Kirby Rolph), is to demonstrate the positive relationship between the enslaver and the enslaved. But, like slave schedules, the concern here is not so much with the enslaved as it is with the white slave owner. The narrative is not preoccupied with sympathizing with Till’s humanity. No concern is shown even for the physical violence she suffered.

In fact, nothing more about her is depicted in the account. Today, no other trace of her life has survived. This is the sort of casual indifference that amounts to the erasure of a human life—a process that was applied to millions of enslaved people. The result is the elision of an entire people’s history.

What happened after Emancipation?

With no more than the name “Old Till,” it is virtually impossible to recover her from the unremembered past. We can only speculate in triumph or horror.

Perhaps once slavery was abolished she fled as fast and far as she could. Or, perhaps she quietly settled down somewhere nearby as Duncan did. Wise Wood suggests that after Emancipation, Duncan contentedly settled in the nearest town to the Wood family farm, in part, out of a sense of loyalty.

But testimony from formerly enslaved African Americans documented by the Federal Writers’ Project reveals other possibilities.

Henry Dant, who was enslaved on a farm in the same county as the Wood family farm, insists that slaves were provided no resources upon Emancipation and couldn’t go far. Many former slave-holders resorted to enticing the people they had enslaved to stay, some even offering financial temptation.

Emma Knight’s mother was made such an offer: “We stayed a while but she never got no money.” William Black even admits the man who had enslaved him was “nice” but nonetheless “we were so glad to be free that we all left him.” He eventually settled in Monroe City, one of a handful of communities in the area that many emancipated African Americans moved to, including Warrick Duncan.

This is the sort of casual indifference that amounts to the erasure of a human life — a process that was applied to millions of enslaved people.

But Wise Wood gives no information regarding the whereabouts of the woman he calls “Old Till.” Here, his earlier reasoning about Duncan’s loyalty falls short. Till is nowhere to be found and he doesn’t mention her again. Perhaps she wasn’t so loyal, and he doesn’t want to share this. Or, perhaps she simply died of old age and so didn’t merit further commentary in his eyes.

Speculation abounds.

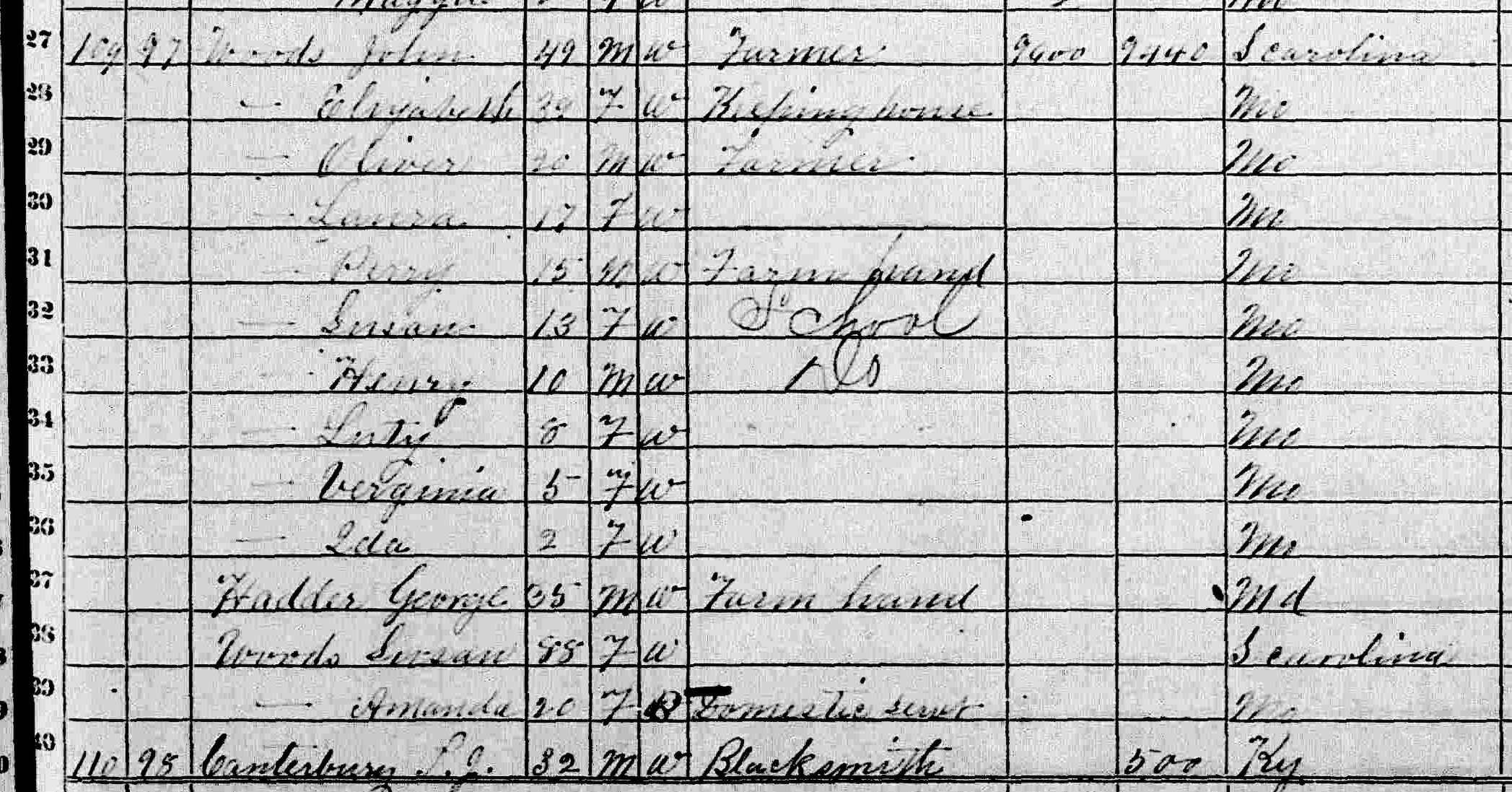

One puzzling seed for this kind of speculation shows up in the 1870 census. It was the first census to comprehensively include African Americans. Henry Wise Wood was 10 years old at this point. Living with him on his family’s farm was his grandmother, John Oliver Wood’s mother, Susan. Immediately under Susan’s name is that of Amanda Wood, a 20-year-old domestic servant who, surprisingly, is identified as Black.

Who is this mysterious Black woman?

An adopted child? Seems unlikely. Where did she come from? She was not included in any previous census. This exclusion, along with her last name, strongly suggests she was enslaved prior to abolition. Could she be the child of a complicated relationship? An illicit coercion? Might John Oliver himself be the father? Might “Old Till” even be her mother? Perhaps 20 years earlier Till wasn’t so “old” and perhaps… But, who knows?

This is a feature of the omitted stories of Black history across this continent: “Who knows?”

This is a feature of the omitted stories of Black history across this continent: “Who knows?” One is left with speculative fancies because there simply is no extant information. One of the tragedies of slavery’s legacy is that it erases so much.

Restoring what has been erased in Alberta

This raises a difficult question for us in this part of the world: what kind of attention should we give to the unrecognized histories of Albertans who have a connection to the institution of slavery? Canada has a long tradition of overlooking the slavery that took place on its own soil.

Is it any surprise that the economic, social, and historical gains which undoubtedly propelled a class of people in the United States seem distant and unconnected to us? This is especially so in the prairie provinces where, in the cases of Saskatchewan and Alberta, slavery was abolished in the U.S. decades before the provinces came into existence.

What attention should we give to unrecognized histories of Albertans who have a connection to the institution of slavery?

But many, many people who settled here came from the United States. Some, like Henry Wise Wood, emerged from the antebellum system and were beneficiaries of slavery. While there is no evidence that Wood consciously subscribed to or promoted white supremacy, he did come from a family that gained from the labour of enslaved people; he benefited from the prosperity of successful family farming and ranching businesses in both Missouri and Texas; and his family’s financial stability contributed to his ability to capitalize on economic opportunity in an entirely different part of the continent.

He was a farmer, yes, but he was an economically robust, well-connected, politically knowledgeable farmer. All of these conditions were supported if not created by socioeconomic realities driven by the engine of slavery.

Historical accounts of Henry Wise Wood often point to his prior experience of the American agrarian revolt contributing to the success he had in assessing its later, Albertan iteration. Can we really count one aspect of his American life experience as foundational and meaningful while completely dismissing another?

Although Wood has been memorialized in a number of ways, including a high school named after him in Calgary, there is in fact no statue. No statue, though, shouldn’t mean no reckoning. Just a little scratching beneath the surface reveals slavery's place in the life of one of the central figures of Albertan history.

What might more rigorous, comprehensive searches produce?

White people’s relationship to slavery, racism, and the renderings of both in history and literature has always been complex, variantly fraught with anxiety, frustration, sincere concern, angered rebuttals, stultifying guilt. But this complexity should not prevent honest questioning here in Canada.

In the U.S., every year, it seems, a classroom reading of Huckleberry Finn or Tom Sawyer resurrects the controversial debate of whether or not Mark Twain was racist. On the one hand, the Missouri man’s writing on race is read, unmitigated, as villainy or heroism, and on the other hand, as unresolved and paradoxical. In either case his texts offer opportunities for the contemporary American relationship to slavery to be publicly examined.

For honest exploration to take place here, though, the connections need to be revealed.

But let me be clear: I am less interested in uncovering the connections between Alberta and slavery for the sake of taking down monuments than I am in restoring what has previously been erased from our collective knowledge.

Perhaps upon considering these connections, someone somewhere in Alberta will want to tear down a monument with Wood’s name. But I would prefer to erect one instead, two in fact, to Warrick Duncan and Till, for contributions rendered the Wood family of Ralls County, Missouri, or, for what James Baldwin might wryly recognize as the evidence of things not seen.

Bertrand Bickersteth’s award-winning collection of poetry is The Response of Weeds. He lives in Calgary, teaches at Olds College, and writes about Black identity on the Prairies.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!