Photos: Jeremy Klaszus

Slow and small: Adventures in printing

Endless growth is not the goal.

Today is The Sprawl's sixth anniversary. We are committed to serving Calgarians through in-depth local journalism, and we believe in doing this work well. If you value the work The Sprawl does—our Sprawlcasts, our weekly newsletters, our comics or all of the above—please support it! Thanks for reading and listening, and here's to the next six years.

This past summer, while on sabbatical, I got obsessed with the history of the printed word.

I guess that after nearly six years of publishing The Sprawl, and two decades as a journalist, it occurred to me that I should learn what I had been up to for all these years.

This particular adventure started—as it often does!—at a local bookshop, Sigla Books, which shares space with Loophole Coffee Bar on the west side of downtown.

It's difficult for me to go into Sigla without spending at least an hour chatting with the proprietor, David Sidjak. (For this reason I don’t go as much as I should—I can’t not go down some interesting path of conversation with David!) I figured we’d hit it off as soon as I saw some old signs from defunct local bookstores leaning against his wall: Wordsworth, De Mille.

I asked about the signs, and soon we were talking about the history of bookshops in Calgary, what they say about the soul of a city, and the enduring value of print in an online world.

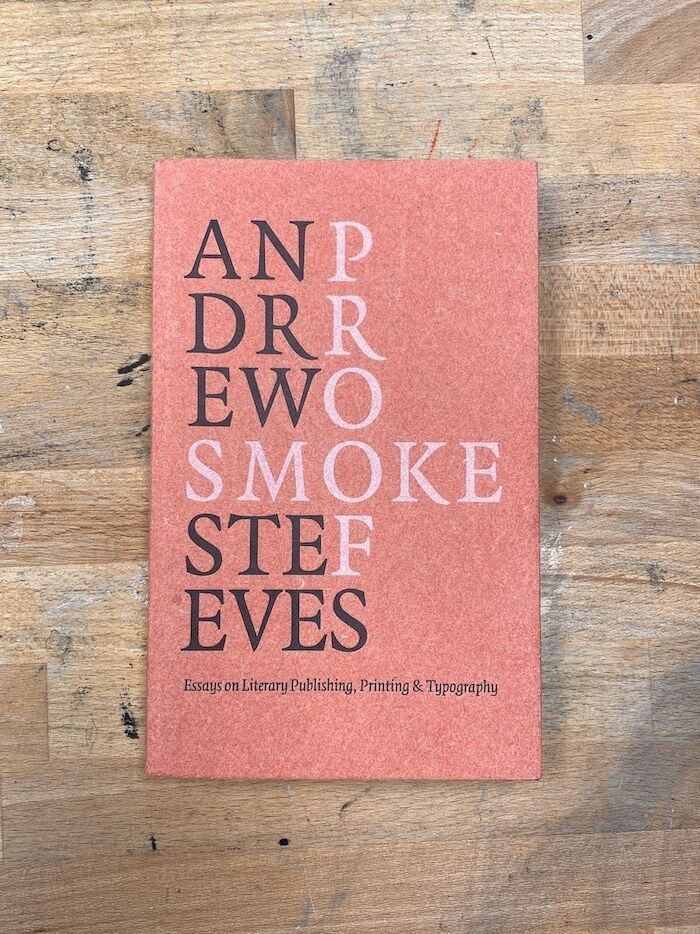

On this particular day in May, after our meandering conversation, one book on David’s shelves caught my attention: Smoke Proofs: Essays on Literary Publishing, Printing & Typography by Andrew Steeves, a former journalist who co-founded Gaspereau Press, a small publishing house in Nova Scotia.

Who knows why certain books find us at certain times in our lives?

Smoke Proofs found me at exactly the right time. Steeves's reflections on publishing, literature and journalism went off like a bomb in my burned-out brain, lighting up my imagination.

I think that publishing is all about paying attention in the same way that reading is all about paying attention.

Here was someone who was employing old, discarded tools, including letterpress, to print and publish elegant paperback books of poetry and essays. Most fascinatingly to me, Steeves wasn't driven by some nostalgic or romantic ideal, but by service to the community, deep regard for his time and place, and a keen awareness of the tradition he was working in.

Steeves was using a mix of old and new technologies, not to retreat from the world and its concerns but to engage with them. In Smoke Proofs, he argues compellingly for this posture, warning against the temptation “to rarify the beautiful and exile it outside of our common experience.”

I suppose I was drawn to the book by the high level of craftsmanship, which is evident in the cover alone, designed and handprinted by Steeves himself. All of Gaspereau's titles are similarly striking—“homespun,” to use Steeves's word. But as I read, I became intensely interested in Gaspereau's small-scale business model.

What struck me most about Gaspereau is that they are not trying to publish the next Canadian bestseller; in fact, they are deliberately not doing that, and have thereby built up a small but dedicated readership. “We’re not selling books at a volume that would make a multinational publisher happy,” Steeves says in an interview in Smoke Proofs.

Instead, he likens Gaspereau to a family farm, where the idea is to leave the land a little better than you found it and to do work that nourishes yourself, your family and your community.

“I don't need to put a lot of profit away for tomorrow, I just need to be able to feed my family,” Steeves continues. “And I need to be careful enough so that if this crop fails, the bank can't step in and take my business or my home. So you're careful, you're wily, but at the end of the day you keep going not because you are getting ahead but because you feel that you are doing something of value for your family and for your community.”

I thought: That’s it!

I was hooked, and ordered more Gaspereau books, including a newer Steeves essay called “Notes on Printing and Publishing Literary Books.” In it, he talks about how his “motivation for publishing books is aligned with my lifelong interest in journalism.”

“I publish literary books because I think they can help the community to understand what is happening to it and through it, articulating what it's like to be alive, here, at this time and in this place,” he writes.

I realized that this is exactly what I want to do, and get to do, with The Sprawl.

As all of this was happening—my long morning walks to bookstores, my obsession with Gaspereau Press and printing—social media as we have known it was changing. This became especially true for Canadian news organizations, which are blocked from sharing news on Facebook and Instagram because of the standoff between the federal government and Meta over Bill C-18.

That leaves us with the tattered wreckage of Twitter as a distribution tool—and a lousy one, at that.

For years, I had thought the idea was to get as many people as possible to read (or listen to) The Sprawl, using social media as tools to accomplish this. The bigger the audience, the better! There was always someone more to reach, and it was my job to reach them.

Now I wondered: What if it that’s not it at all?

If social media was collapsing as a distribution tool for journalism, maybe this opened up new possibilities. And not just to jump onto newer, similar platforms. Maybe, instead of spending my weekends invested in social media, as I have for years, I could be a little more present to the people around me.

Maybe there was another way to live—to be. And maybe there were other ways to publish, too.

If social media was collapsing as a distribution tool for journalism, maybe this opened up new possibilities.

Here is a specific example. Last Friday, at around 4:30 p.m., I had just gotten the latest Sprawlcast from my podcast editor and was about to give it my usual “test drive,” listening to the final cut while walking the dog.

Before I headed out the door, my 12-year-old son asked me, “Do you want to go camping, Dad?”

In the past, I would have said I can't, because “I have to” work. “I have to” get the transcript ready and “I have to” get it ready to post on social media, and so on.

But this time it hit me: I don't have to.

The episode was done. I just had to listen and upload the final cut. The weekend newsletter was ready. As for posting the transcript—it could wait until the following week.

All I had to do was nudge the podcast out the door for people who appreciate such work. That would be enough.

I looked outside. Blue sky. No smoke. Clear forecast.

Do you want to go camping, Dad? Hell yes.

We hit the road for Kananaskis that evening, spent the weekend together and biked the Bow Valley Parkway from Banff to Johnston Canyon (which I highly recommend—it's closed to car traffic until the end of September). Then, after the weekend, I posted the transcript.

The world did not end. To me, it even seemed a little brighter.

Lately I find myself wondering: Which tools do I want to pick up? Which ones do I want to leave alone? And which do I want to learn how to use?

These days I am drawn to podcasting and printing. One of these I can do well; the other, I am learning. Thankfully my new office is in a print shop.

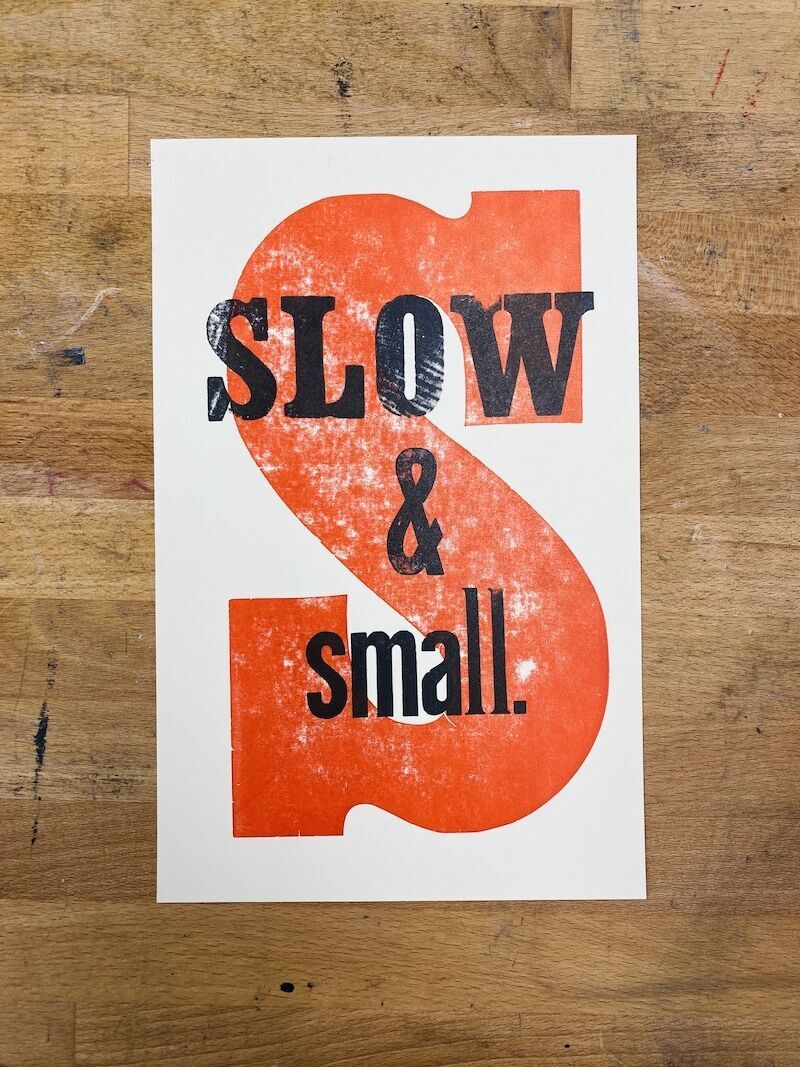

On Monday, I got a tutorial from Monica Kidd, the shop’s proprietor (whose poetry books, on a side note, have been published by Gaspereau). We printed using her tabletop Chandler & Price press. I had in mind a short bit of text, the three words I keep thinking of as I re-enter The Sprawl after burning out: slow, small and sustainable.

These words are the right idea: slow + small = sustainable. But something was off. The word sustainable is so long, and felt out of place with its eleven letters—more than double the number of letters in each of the other two words.

“Kind of an overused word anyhow,” I said.

“Jargony,” Monica agreed.

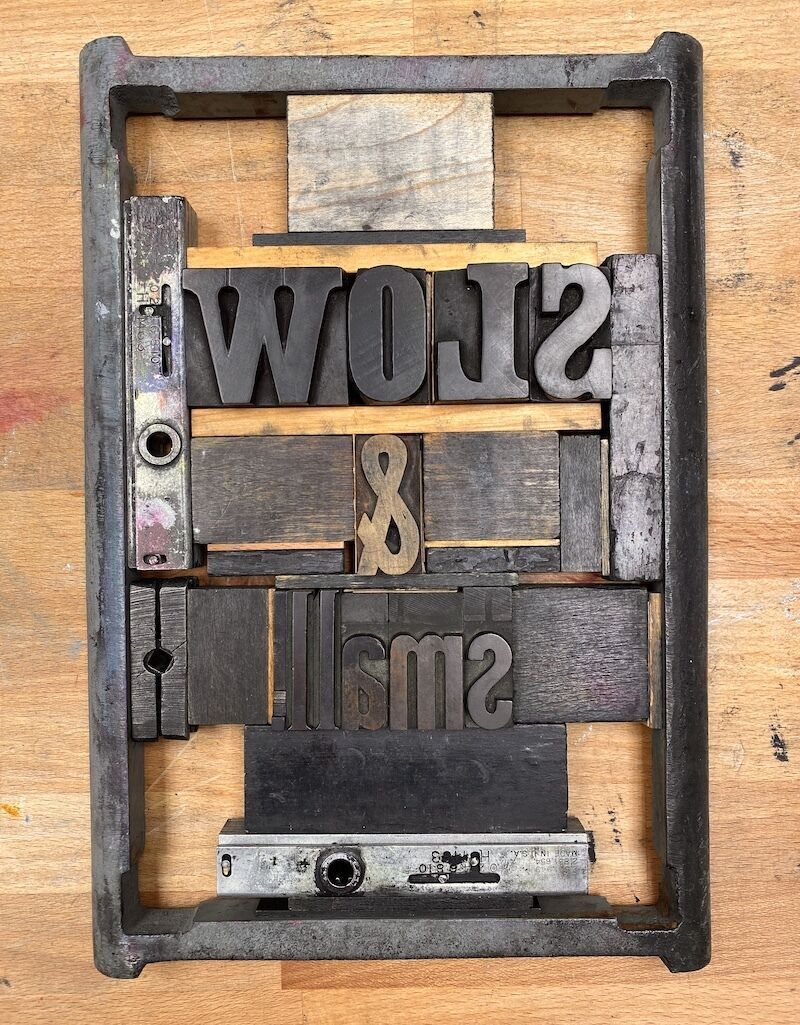

Since we were using chunky wood type that would have to fit in a 6.5” x 10” frame, the solution was clear. Toss it!

Slow and small. Two words, plus an ampersand.

There is a whole lexicon of printing that is new to me. You set type in a chase. The wooden blocks that hold the type in place are called furniture, and the thin, narrow pieces of wood between lines are reglets. Once you have all that stuff ready, you tighten quoins to make everything snug.

To print, when you pull down the lever of the press, the platen is raised against the inked-up type. When ink meets paper—this is the kiss.

And presto! You have printed.

So there's my first print job (with no small amount of assistance from Monica!). Slow and small. Edition of eight. One will go on my wall to remind me what The Sprawl is about.

The problem with working in a print shop, of course, is now I can't stop thinking about printing, about different publishing possibilities. I may or may not have a problem. But I can tell you this: Messing around with type and ink sure beats doomscrolling.

I have lots to learn—about kerning, leading, inking and pretty much every other aspect of printing. But there is something satisfying about making something, no matter how imperfect, on a hand-powered press.

For now, I'm just enjoying following my curiosity where it leads.

Jeremy Klaszus is the founder and editor-in-chief of The Sprawl. This dispatch was originally sent as a newsletter on Saturday, September 16. Sign up below to get the latest from The Sprawl when we publish!