City hall set a target of one in five Calgary kids walking to school by 2025. Photo: Rob Moses

Walking to school should be easy. Why is it so hard?

Change is slow in a city built for cars.

When Tiyam Kardan and her husband moved to Canada from Iran in 2016, she researched schools for her young son.

She looked up online school rankings, and then found an apartment close enough to a “good” school where her son attended for his first years of education.

A few years later, the family moved to a larger home in the suburbs, and instead of choosing the school with the highest ranking, Kardan sent her son to their Calgary Board of Education designated one.

Though the new school doesn’t have the same high ranking as the one they first chose, Kardan has found that her son is thriving. The school is smaller, he is happier and is doing better academically.

Kardan attributes much of his increased happiness to a factor that is often under-appreciated in Calgary: her son can get there on his own, walking with a neighbour who lives across the street. The two are then joined by another child who lives a block away for the rest of the commute.

At the end of the day, Kardan’s son gets home before his parents, so has a key and lets himself in.

“I cared too much about school ranking, but I learned it’s not that important,” Kardan said. Walking to school on his own has had unexpected value.

“He has more confidence,” said Kardan. “He is more sociable.”

The hidden benefits of walking to school

Like Kardan’s son, my eleven-year-old son really wants to be independent. He leaps at the opportunity to walk pretty much anywhere on his own, to meet friends in the park or to just bike around.

He's old enough to listen to the news and understands the gravity of current affairs: pandemic, political divisions, even war. Opportunities to navigate our neighbourhood on his own have become even more valuable with this new global awareness.

On the days that he walks home from school by himself, it takes him twice as long as when he’s driven—but, as with Kardan’s son, there are hidden benefits. Lost in his own thoughts, not watched over by any adult for a little while, he gets to manage his own time.

He says that when he walks, he feels less stressed: “I get to spend time in nature and focus on what’s around me.”

There is extensive research on the benefits of outdoor activity for kids—including improved mental health, the development of spatial orientation skills, and even long term physical fitness. Outdoor Play Canada emphasizes that “children who engage in active outdoor play in natural environments demonstrate resilience, self-regulation and develop skills for dealing with stress later in life.”

The benefits of kids walking and biking are well-documented—so why is it so hard?

A 'mayhem of vehicles' descends on schools

Calgary is designed for cars, and incentivizes driving. Take our commute as an example. On the days my two sons walk to school together, I go with them.

We live near 20th Avenue N.W., which runs parallel to 16th Ave.—the six-lane TransCanada highway only four blocks away. To our frustration, both streets share the same 50 k.p.h. speed limit, so shortcut-seeking commuters often choose 20th.

Several speeding cars usually fly by as we wait for traffic to stop at the crosswalk on 20th Avenue. Sometimes the drivers wave apologetically. Eventually someone notices us in time to screech to a stop as we hurry across. This intersection is dangerous and unpredictable—and the city is full of intersections like these.

Meanwhile, at my children’s school, like most schools, the building gets surrounded by a steady stream of cars every day at drop-off and pick-up times. There is a mayhem of vehicles, some large enough that a child walking beside the car is easily unseen. And the air quality, especially on a cold day in the wintertime when the vehicles are idling, is terrible.

David Suzuki, arguably Canada’s best-known environmentalist, addressed this in a recent Globe and Mail interview. He was asked: “What is one thing anyone can do tomorrow, to make the tiniest change?”

Suzuki’s response: “I always tell parents, I know you love your children—so stop driving them to and from school. That’s a simple thing.”

But not driving them is easier said than done. “Safety concerns of parents remain a predominant barrier to active transportation,” states a recent Participaction report, which gave Canadians an overall grade of D- on active transportation.

I cared too much about school ranking, but I learned it’s not that important.

The Participaction report says that across Canada, only 21% of five to 19-year-olds use active forms of transportation (walking or biking) to travel to any of the places they go—not just school, but also friends’ houses, malls or parks.

Startlingly, even in walkable neighbourhoods, “while physical activity among adults tends to be higher, the same is not true for children.”

So while adults may walk to nearby amenities, kids are still being driven.

It seems we're stuck in a loop: We drive our kids because it doesn’t feel safe for them to walk, and it doesn’t feel safe for them to walk because there are so many cars.

This is doubly challenging in a sprawling city like Calgary, where our education system prioritizes parental choice over getting all kids to attend local schools. And many families don’t have a school within walking distance at all.

City hall is pursuing incremental change

Public schools are intentionally set up so that every child should be able to commute, independently and safely, to their designated school—at least in theory. If kids live more than a few kilometres from the school, the school board arranges buses, assigning stops that are within a short walking distance from each child’s home.

Lately there have been some hopeful upgrades along my kids’ commute. There are new speed bumps on the roads around the school. Intersections are more visible, with yellow traffic calming curbs flanking well-marked crosswalks and ramps that are thoughtfully placed.

These changes have helped those who do go car-free. They also help parents who avoid the mayhem by dropping kids off a little further away from the school.

The City of Calgary has numerous policies—including the Calgary Transportation Plan and the pedestrian strategy—that call for pedestrian and cycling infrastructure to be prioritized.

It seems we’re stuck in a loop: We drive our kids because it doesn’t feel safe for them to walk, and it doesn’t feel safe for them to walk because there are so many cars.

The city’s pedestrian strategy, approved by council in 2016, set a goal of getting 20% of kids walking to school by 2025. That's a slight increase from the 18% who walked to school in 2011, but well below the 27% who walked to school in 2001.

City transportation planner Katherine Glowacz is hopeful about reaching the 2025 goal through the city’s Active and Safe Routes to School program, which focuses on making the areas around schools safer and more welcoming for walking and cycling.

“Citywide, we know trends can take longer to see the shifts across the city, but where we do work with schools across the city, we see changes,” she said. “We see more students walking and wheeling.”

While there are a lot of engineered changes that make a pedestrian commute safer, including curb extensions and signage, Glowacz says the real change “is often about a culture shift for families.”

Glowacz says that each school the city works with sees between six to nine percent more kids getting to school car-free, pretty much right away. In 2021, the city worked on improvements around three schools. In 2022, they are planning upgrades around another 17.

City admin is slated to report to council before July with recommendations—including funding recommendations—for expanding the Active and Safe Routes to School program. “We’re encouraged to see that council is excited,” Glowacz said.

Students coming up with their own solutions

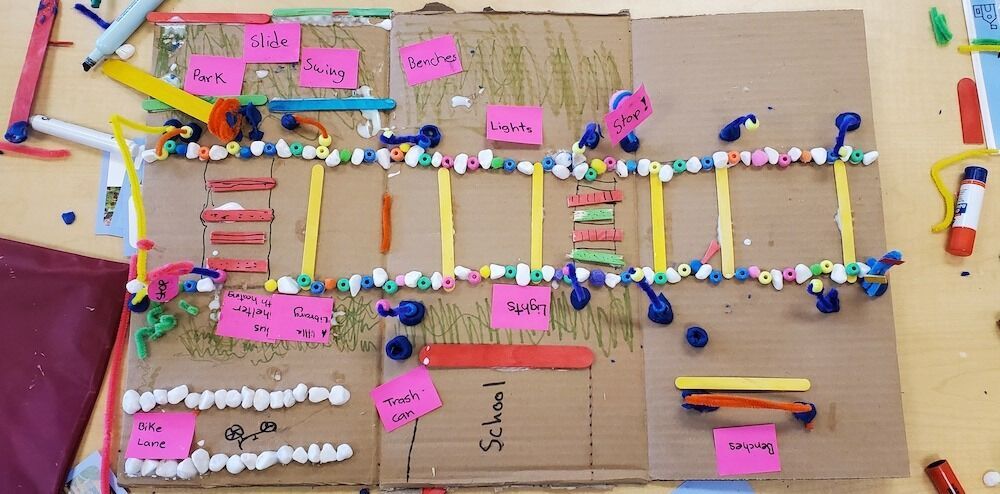

Meanwhile, Sustainable Calgary is working directly with students in three different parts of the city—Connaught, Martindale and Meridian—to promote the use of active transportation modes. The group facilitates workshops with elementary-aged students, helping the kids reimagine the areas around their schools, making them safer and more welcoming.

“When we start with the kids we say: What are your favorite places to walk?” said Celia Lee, Sustainable Calgary’s executive director. “And we hear a lot of things about green spaces or beautiful spaces, spaces where you could zone out, where you could daydream safely without worrying about being hit by a car.”

The design plans that Sustainable Calgary helped students create include colourful paint, areas to play and rest, planters and greenery. The goal is to make welcoming spaces that children can more easily navigate on their own. (Sustainable Calgary is currently fundraising to make this happen.)

As students work on the projects, they are not only honing their design skills, but are learning to advocate for their own well being.

The benefits of these community improvements go well beyond the students themselves.

“I think a lot of us can gather around the idea that we need to get kids safely to school, we need to keep them healthy,” said Lee. “We need to make them champions for climate action. But then, if we start doing that, we've made the neighbourhood better for everybody.”

Turning bad bike racks into usable ones

A decade ago, the city painted bike lanes onto streets near our home—including the steep 10th Street N.W. hill into Kensington. We were elated, thinking our kids would one day be able to safely bike with us on their own wheels for after-school errands and weekend bike rides down to the river.

Over the years we realized that paint on the road isn’t enough to make the busy street kid-friendly. As our children got older we gave up on letting them ride there on their own bicycles.

Laura Shutiak, executive director of a new organization called Youth En Route, is trying to get more kids like ours back on their bikes. Youth En Route is working to empower youth “to use active and independent ways to get where they are going.” even when the route is, like 10th Street N.W., less than perfect.

When we talk over Zoom, it's clear that Shutiak is ready for this conversation—one she has regularly. She has done her research, is ready with city budgets, statistics and a compelling vision. Her organization’s goal is to get kids biking independently for trips under five kilometres.

“We need to stop thinking of bike riders as those guys in spandex,” she said.

Youth En Route goes into schools, primarily high schools, and identifies the reasons kids are being driven, or driving themselves, to school. She finds often the barrier isn’t bike ownership.

At one school, 88% of kids owned a bike but hardly anyone rode.

The barrier is often bike security.

At schools where students and parents are afraid of bikes being stolen, Youth En Route steps in with solutions.

At one school, finding the price of a good bike lock was prohibitive for some, so they purchased a shipping container where kids could store their bikes together. It was locked up in the morning and opened up at the end of the school day.

Another solution is setting up bike lock libraries so kids can check out a good lock for the day. Cameras and overall bike rack visibility are also helpful, Shutiak says.

Sometimes biking to school isn't something students have thought of before—and they don't know the best way to go. In that case, Youth En Route will bring out maps and help the students find the safest route, navigating city infrastructure that was clearly designed for a car-centric society.

Shutiak has environmental concerns that fuel her wish to see more kids using active transportation to get to school. But, like Tiyam Kardan and my oldest son, she emphasizes the mental health benefits.

“There are so many benefits to biking,” Shutiak says. “We ride our bikes for health and fitness and fun. You just feel good.”

Kirti Bhadresa writes both non-fiction and fiction. She has a short story in the current issue of The Fiddlehead and another in the upcoming edition of Prairie Fire.

Support independent journalism.

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!