Why has Calgary stalled on bike infrastructure?

City nowhere close to 2020 target for cycle tracks

The 5th edition of the Sprawl—the Summer Bike Edition—is here! This is the first story. If you value our work, please support the Sprawl so we can keep doing in-depth local journalism like this!

When city council approved Calgary’s cycling strategy in 2011, it set an ambitious goal: build 30 km of separated cycle track by 2020.

At the time, the city had no cycle tracks. The idea was to give more transportation choices to Calgarians while making the city more sustainable. It would open possibilities for people—not just men comfortable riding in car traffic, but also women and families who were interested in cycling but concerned about safety.

And in 2014, Calgary went for it in a big way.

Urged on by a group of citizens and businesses who rallied behind a cheerful “Calgarians for Cycle Tracks” campaign, council voted 8–7 to create a pilot downtown network.

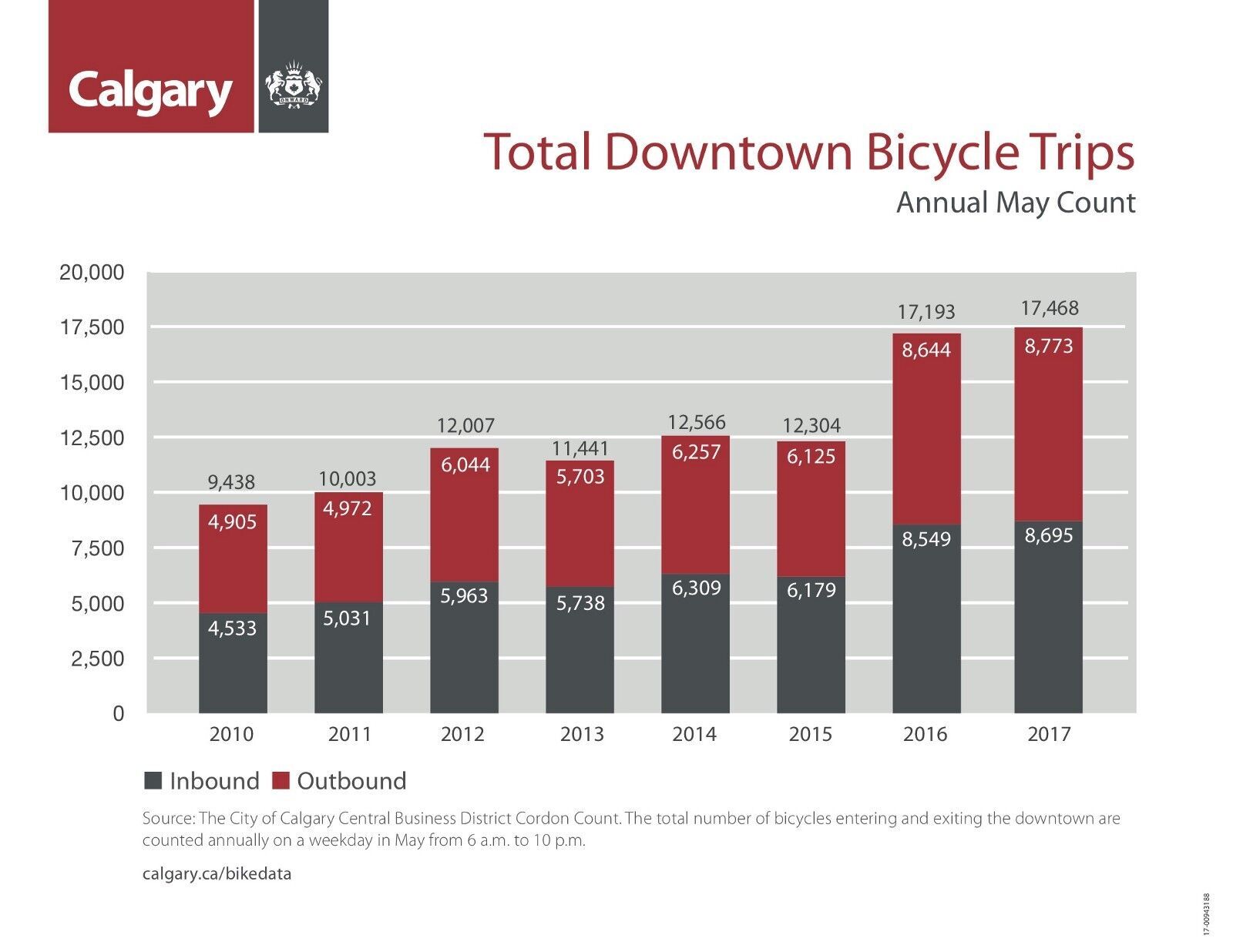

In the time since, the network has been hailed as a success on myriad fronts, regarded as an example to follow by cities across North America. Bike ridership has risen downtown, female ridership has increased slightly to 1 in 4 cyclists and even kids are getting in on the action.

The percentage of downtown commuters who cycle has risen from 1.9% in 2010 to 3.8%, just shy of the 2020 goal of 4%.

But even as the numbers rise, efforts to build new cycling infrastructure have stalled thanks in part to the recession.

Capital funds have dried up almost entirely. The city built just 0.1 km of cycle track last year: a single block at the south end of the new zoo bridge on 12 St SE in Inglewood.

The slowdown has left many two-wheeled commuters wondering what happened to the momentum.

“The problem is not necessarily that we’ve lost momentum, but we’ve definitely lost the will to fund projects,” said former Bike Calgary president Kimberley Nelson, who was at the forefront of the often-acrimonious cycle track debate. “I think there’s a lot of frustration bubbling and maybe that’s what we need again.”

The recent debate over 2 St S.W. in Mission seems to sum up the state of things.

The city proposed a painted lane, arguing that the road isn’t wide enough for a separated track. The local community association fought back and now city hall is looking at making it work.

“The city is falling quite short of following its own policies,” said Agustin Louro, current Bike Calgary president. “All the engagement happens and the trust is there from Calgarians that the city will then enact those policies.”

“By not following through on implementation, it really puts the onus back on the citizen to be a watchdog.”

The next big test will be in November, when the next four-year budget is up for debate at city council. This will determine how much, or how little, city hall replenishes the budget for cycling.

‘Edmonton is leaving us in the dust’

When Calgary opened the cycle track network in 2015, bike commuters in Edmonton looked enviously southward. But Alberta’s capital has sped ahead since. The city opened its new 7.8-km downtown bike network last year and has more separated routes in the works.

“We’re often on the vanguard on a topic, but other cities catch up quickly,” said Calgary Councillor Druh Farrell. “We didn’t stay in the vanguard very long. And Edmonton is leaving us in the dust.”

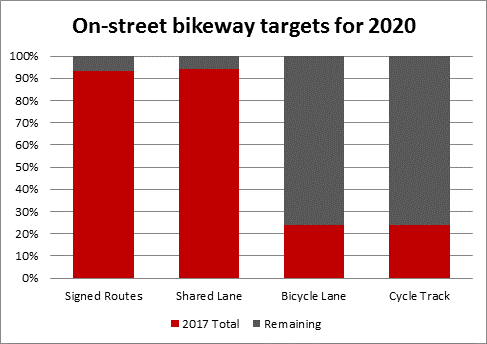

Calgary is nowhere close to meeting key 2020 targets for on-street infrastructure. In total the city has built 7 km of cycle track citywide, not yet achieving one-fourth of its target.

The city is likewise behind on painted lanes, having painted 43 km by the end of 2017. The target is 180 km.

Over the past decade, council has repeatedly committed to bike-friendly policies, but budget follow-through has been spotty.

“The challenge is that lots of policies and strategies are created with 10-year horizons that have to go through multiple budget cycles,” said Councillor Evan Woolley. “One of the things we’ve always been challenged by is how can we tie the creation of a policy to investments?”

In 2009, council approved the Calgary Transportation Plan: “Enable public transit, walking and cycling as the preferred mobility choices for more people.” Then came the cycling strategy in 2011. And in 2014, the city passed its complete streets policy, which calls for multimodal streets that give priority to walking and cycling.

The downtown cycle track network was borne in part out of these policies, but even now the policies are often applied selectively. “In particular the Complete Streets Policy is not being followed on a number of projects,” said Louro.

As city hall goes on a blitz of redeveloping main streets throughout the city, it’s not always incorporating cycling infrastructure. Bikes are instead being bumped to neighbouring streets to preserve parking, as is happening on 17 Avenue S.W.

Woolley contends that cycling hasn’t fallen off the agenda at city hall, pointing to the downtown cycle track network. “This is an unbelievable piece of infrastructure that we invested in that has seen great success,” said Woolley. “To hear bellyaching from people that we haven’t done anything in a year after making this massive investment seems a bit shortsighted to me.”

He’s optimistic heading into November’s budget deliberations. “I would expect that our allocation of capital money in transportation should not only reflect the modal split, but should also reflect where we want the modal split to go.”

Little funds left for ‘active modes’

The $22M in one-time funding that came with Calgary’s cycling strategy has been spent, along with the $13.5M funding for active modes from the 2015-18 budget. “This year we’re basically down to around $1M for our total budget for walk, bike and community traffic,” said Tom Thivener, the city’s coordinator of active transportation projects.

Thivener’s team of 14 is responsible for walking, biking and community traffic — all of which are grouped under the banner of “livable streets.”

“To hear bellyaching from people that we haven’t done anything in a year after making this massive investment seems a bit shortsighted to me.”—Councillor Evan Woolley

The approval of the pedestrian strategy in 2016, while badly needed, also hampered the cycling file. “The pedestrian strategy was supposed to come with capital dollars and new staff positions but it didn’t, because of the recession,” said Thivener. “That’s definitely a factor in what we can do.”

The livable streets department is also inundated with traffic calming requests.

“A lot of the streets that we work on, such as the collectors, have really huge community issues with speeding,” said Thivener. “So communities are asking us left and right to come in and retrofit the corridors with curb extensions or pedestrian refuge islands or other devices to slow vehicles down. Our budget is one of the best ways to do it.”

While cycling is sometimes portrayed as an example of city hall largesse—a place to trim the fat—in reality it’s a tiny fraction of the transportation budget.

In the 2015–18 budget cycle, city hall allocated $13.5M for active modes citywide. To put that number in context, a single interchange that opened last summer—Bowfort Road/Trans Canada Highway—cost $72M.

“You’ve got two different portfolios, both working towards vulnerable users, both stripped to the bone,” said Nelson.

“The amount allocated specifically towards pedestrians and bikes is basically a rounding error, and yet that’s the first thing that gets cut. So you’re not even looking at the crumbs, you’re looking at the crumbs of crumbs — and then patting yourself on the back for trimming down the budget.”

Cycle tracks to get patchwork upgrades

Three years after it opened, Calgary’s downtown cycle track is languishing in places, particularly the west end of 8 Ave SW. Originally built as a temporary pilot, there’s no budget to fully convert the cycle tracks into permanent infrastructure, despite council voting in 2016 to keep the network for good.

“The direction from council was to make upgrades as time goes on and kind of live with the temporary things to reduce costs,” said Thivener. “I think we’re honestly looking for projects of opportunity, where maybe the street is getting redeveloped — like 8th Avenue SW on the west end, there’s clearly some redevelopment happening. There are opportunities to work with the developer.”

Meanwhile, the network is still missing some key links. The east end of 12 Avenue SE and south end of 5 St SW both suddenly end, awkwardly spitting cyclists into car traffic.

“Late last year we started coming up with plans on how to connect that better,” said Thivener of 5th Street. “The councillor for the area is a little nervous about some of the impacts: either removing parking or reducing a travel lane. Because something has to give if you take the existing road for what it is between the curbs. So he’s encouraged us to kind of do a master plan.”

“That’s definitely feasible out there, it’s just not an endeavour that’s funded at the moment.”

Woolley, the area councillor, says that given the street’s design and history — it was previously a one-way outflow from downtown, and the neighbourhood fought to make it a two-way street again — slapping down a cycle track doesn’t make sense.

“Sometimes our bike guys do bikes at the detriment of other things,” said Woolley. “Their two proposals that they brought forward were keep all of the parking and turn 5 Street into a single lane, single direction out of downtown—or lose all the parking along that frontage street.”

With parking in short supply in Mission, Woolley says there’s an opportunity to carefully make the realm better for all. “The community wants a cycle track but we have to be thoughtful about that. I’m not turning that road into a one-way street again. There’s no way.”

Woolley says the Pathway and Bikeway Plan, which is currently being updated, will also help connect the cycle tracks. “One of the focuses of that plan is how do we connect the pathways to the lanes, and how do the lanes connect to the cycle track? There’s a huge component of missing links that we need to invest in.”

“There will very hopefully be capital money for that.”

City starting to expand beyond downtown

If there’s an upside for bike commuters to the recent infrastructure slowdown, it’s that the city is starting to expand bikeways—city hall’s all-encompassing term for on-street routes ranging from signed routes to cycle tracks—beyond just downtown.

“We had our busiest season delivering bikeways last summer,” said Thivener. “I don’t know that it made a lot of media splash, because most of the facilities were not downtown. They were connections out into the communities.”

Most of the remaining budget is being spent in Midnapore on Midlake Blvd. “It’s basically community traffic calming with some school site safety improvements, including [painted] bike lanes,” said Thivener. The city doesn’t have enough funds to complete it this year, so will finish in 2019.

The new car-free, bike-and-BRT bridge over Deerfoot Trail also opens later this year, linking Inglewood with Forest Lawn.

Thivener’s department, meanwhile, is building its business case for the next budget cycle.

“I expect we’ll get replenished so that we can continue doing some of the corridor work, some of the spot improvements that we’ve been doing,” said Thivener. “And have enough money to at least operate and keep the status quo going—in terms of being able to deliver two or three corridors a year and do some other miscellaneous intersection improvements and things like that.”

The budget will determine whether new cycle tracks get installed as temporary infrastructure, like the downtown tracks, or are made permanent from the get-go like Edmonton Trail’s track.

“There are definitely long-term savings when you can go permanent right off the bat because our crews don’t have to refresh the paint and do as many repairs to the green, flexible poles as much,” said Thivener.

‘Why is it a fight?’

For her part, Farrell thinks city administration needs to be less timid on the cycling file, not settling for status quo.

“I say this often: you can determine a city’s values not by their policies but by their budget,” she said. “We have remarkable policies at the city of Calgary and it requires brave decision-making. When the decisions are complicated or difficult, our administration has a tendency to shy away from those controversial decisions.”

“Change isn’t easy. It requires stalwart, constant effort. Our motto is ‘onward.’ That’s not shy.”

She also believes that if Calgary is to get its bike mojo back, citizens will need to speak up like they did in 2014.

“We had noisy but respectful advocates who wouldn’t tolerate the status quo, and they motivated us,” said Farrell. “And they’ve gone quiet as well. I think they needed to rest up but it’s time to start that advocacy again.”

“It’s because of that advocacy that we were so successful.”

At the same time, why should it be up to citizens to continually rehash the issue when city hall has repeatedly endorsed a direction, but failed to follow through on implementation?

“Really, at this point, I don’t think anyone should have to fight for it anymore,” said Nelson. “Why is it a fight? We had our battle. We won. We won with compelling evidence.

“Why are we still having this same argument?”

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

The Sprawl is crowdfunded by Calgarians. If you value our work, please become a monthly supporter of the Sprawl so we can keep doing in-depth journalism like this!

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!