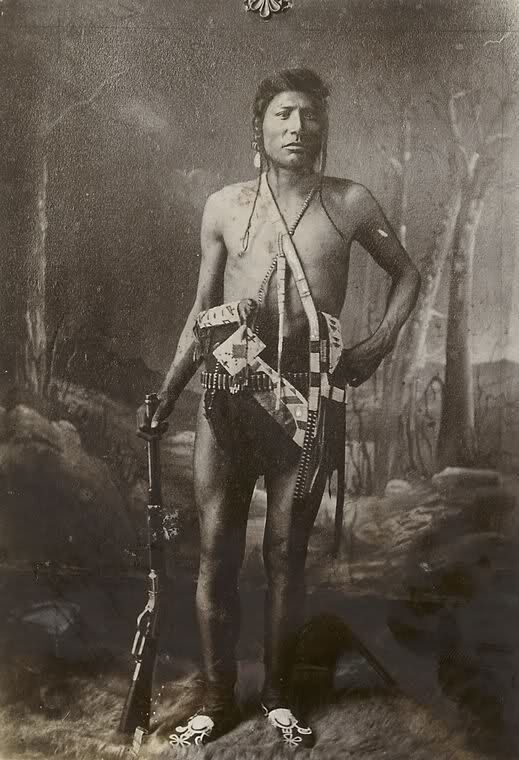

Tsuut'ina Chief Lee Crowchild. Photo: Jesse Salus

‘You can’t just take a name’

How Calgary uses — and misuses — Indigenous names.

Last November, the Stoney Nakoda proposed an alternate name for Calgary: Wichispa Oyade, which is Nakoda for “elbow town.”

The request prompted a response from the Piikani Nation, who pointed out in an open letter that the Blackfoot pre-date the arrival of the Stoney in southern Alberta by a few thousand years, and therefore Blackfoot names should be used—Mohkinstsis is the Blackfoot name for Calgary, translating to “elbow.”

It’s unlikely that Calgary will officially change its name, as Mayor Naheed Nenshi admitted at the time. But there’s no reason why one place can’t have multiple names.

Indeed, as the Stoney and Piikani letters show, most places already do have more than one name—some older than others—even if we don’t acknowledge them all.

The conversation raises larger questions: What’s in a name? Who gets to name things? Does it matter if we use English or Blackfoot or Tsuut’ina or Nakoda? What do our choices in public names say about us?

“In any culture, names are very important. These places all had names for a long time before [settlers arrived].”

Calgary is a young city, founded as a police station in what had long been Blackfoot territory two years before Treaty 7 was signed. Its relationships with its Indigenous neighbours are long and complicated, rich with stories, painful and contentious.

Today, however, the most visible acknowledgement of that shared history isn’t found on plaques or monuments.

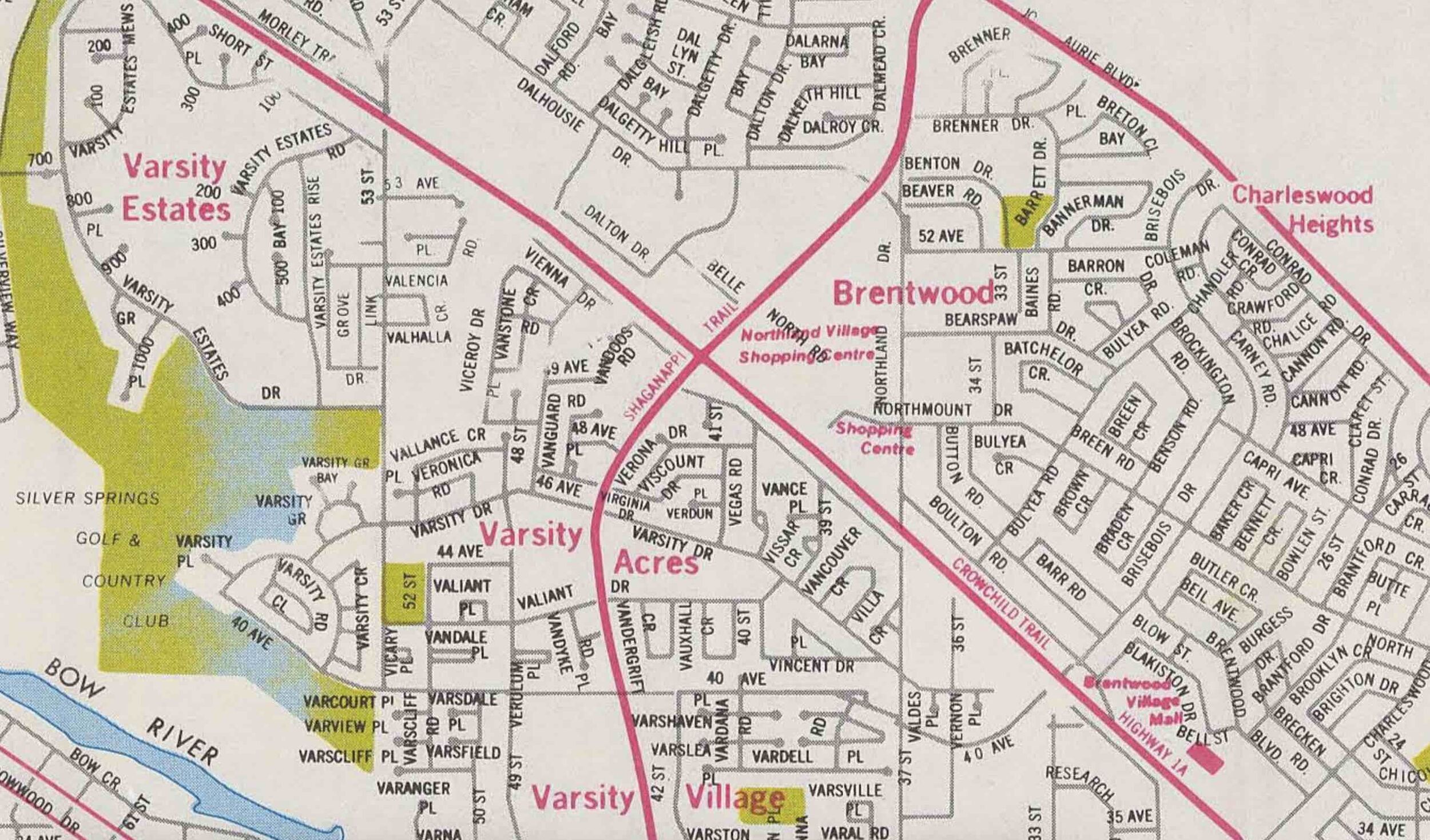

It’s on road signs.

‘It speaks to our history’

The precise origins of Calgary’s affinity for naming major roads with Indigenous names and words is difficult to trace.

Many of Calgary’s arterial roads were built during the ’60s and ’70s, and many were given First Nations names. Since 1976, the city has had official policies recommending that freeways or skeletal roads be named for Indigenous groups or people, but the convention was already well established by then.

Shaganappi Trail is named for the Shaganappi Point area downstream and across the river from its southern terminus, which has had that name since the 1870s.

Shaganappi is a Cree word referring to cords made from rawhide, which settlers used on their wagons.

Sarcee Trail was named with the Blackfoot word Calgarians long used for the Tsuut’ina, with translations from historical literature and living Blackfoot speakers as varied as “strong-willed,” “stubborn ones,” “not good,” and “people who can’t take care of themselves.”

“Blackfoot are notorious teasers. Pretty harsh with our humour.”

The Tsuut'ina migrated south to their present location in Blackfoot Territory a few hundred years ago—hence the potential for derisive names from their rivals.

“Blackfoot are notorious teasers,” said Garret Smith, a local organizer from the Piikani and Kainai Nations. “Pretty harsh with our humour.”

In 1993, the nation changed its name from Sarcee to Tsuu T’ina and later Tsuut’ina, but the road name has stuck.

With the southwest portion of the ring road that runs through their territory set to be named Tsuut’ina Trail, that nation will have two namesake roads in Calgary.

Tsuut’ina spokesman Kevin Littlelight says the Tsuut’ina are proud of having their name on road signs, even if one version is outdated. He provided an alternate definition of Sarcee: “little noses.”

“It’s an honour,” Littlelight said. “It speaks to our history, of the people around here.”

Tsuut’ina Chief Lee Crowchild sees Sarcee Trail as a fight for another day.

“We’re not pressuring that too much right now, but in time, probably we will,” Crowchild said.

There is at least one instance of a name arising organically.

Blackfoot Trail was the literal trail followed by the Blackfoot people for trading, though the former trail and current road don’t exactly align. Bridge construction plans drawn up in 1916 name the road as Blackfoot Trail.

Likewise, Littlelight says the southern leg of Sarcee Trail may have traditionally been the route taken by the Tsuut’ina into Calgary.

Crowchild & Deerfoot

Crowchild Trail and its Bow River bridge, meanwhile, were named in 1966 for former Tsuut’ina Chief David Crowchild, who had worked to build understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures.

According to Crowchild’s grandson, current Chief Lee Crowchild, the route had actually been known as “Crowchild’s trail” much earlier, as it was the path his great-grandfather would follow when returning home after Catholic service in Calgary.

Regardless, David Crowchild gave his blessing to the road name after city officials asked his permission.

But they didn’t offer that courtesy to the descendants of Deerfoot—a renowned Siksika runner who competed in wagered races—before affixing his name posthumously to a freeway in 1974.

“They didn’t even approach my family,” said Treffrey Deerfoot, great-great-grandson of the runner.

He reached out to the city in the early 1990s to find a way of rectifying the situation.

The road was re-dedicated in a 1993 ceremony where Mayor Al Duerr smoked a pipe with Treffrey Deerfoot and others.

According to Deerfoot, as part of that reconciliation the city pledged to erect some sort of signage explaining the name and honouring Deerfoot, but never did.

“It’s another broken treaty, another broken promise,” he said.

'You can't just take a name'

Given the fraught history between Indigenous peoples and settler communities—especially when it comes to acting unilaterally, or taking without asking—the question of consultation and basic respect is an important one, and certainly not new.

“You can’t just take a name,” Siksika Chief Strater Crowfoot told the Herald in 1993. He was unhappy with the northwest development of strip malls and roadways known as Crowfoot.

“No one ever approached my family for permission to use (our) name... There has to be some respect and understanding that we were here first. This is our land.”

Crowchild notes that businesses and organizations have taken his family name without asking—though the Crowchild Hockey Association reached out to him recently, and he is working with them to design a more appropriate logo.

Some of Calgary's road names are no longer applicable, like Sarcee Trail, or Peigan Trail, which uses the old word for the Piikani nation.

Meanwhile, the Kainai (formerly Blood) are missing from the road map of the city, though historical news articles have plenty of quips and comments from city officials mocking the idea of naming a road “Blood Trail.”

First Blackfoot-language street names

Indigenous cultures place high value on connection to the land and respect for the living Earth. Yet, with no sense of irony, settlers thought the best way to celebrate these cultures would be to give their names to paved, polluting conduits that ferry automobiles across a sprawling suburban landscape.

It’s true that giving these names to major roads has ensured their widespread daily usage, and there’s no other city in the world with a street named Shaganappi.

But history shows us that we need to be more mindful—not only in what names we apply and to which things, but also in ensuring the process is respectful and collaborative.

This is especially true for Indigenous names and cultures as modern Calgary reckons with the idea of reconciliation.

History shows us that we need to be more mindful.

One recent example shows how fraught the issue remains today.

In March 2016, city council narrowly rejected a recommendation from the Calgary Planning Commission (CPC) that a new mixed-use development be named with the Blackfoot term for the area: Aiss ka pooma.

This name was suggested instead of the English translation: Medicine Hill. Calgarians may be more familiar with Paskapoo slopes, the corrupted version of the Blackfoot term.

The developer behind the project, Trinity Development Group, had proposed the English name after consultation with Blackfoot elders, and this was city administration’s recommendation.

However, CPC — an appointed body comprised of councillors, administration officials and ordinary citizens — recommended the Blackfoot name in a 7-2 vote, which is how it wound up before council.

Coun. Ward Sutherland, who is Métis, was one of the most outspoken among those who won an 8-7 council vote to scrap the Blackfoot name in favour of the English approximation.

He’d told the Calgary Herald that using the Blackfoot name was “going beyond politically correct.”

Sutherland believed Aiss ka pooma hard to pronounce (ess-ka-booma) and said people wouldn’t be able to spell it well enough for a Google search.

Nenshi, who voted against the motion to scrap the name, pushed back on these assertions during council.

“It is a reason that flies in the face of inclusion, that flies in the face of kind of community that we want to build here," said Nenshi. "As I said, when your mayor’s name is ‘Naheed Nenshi,’ you get to learn how to pronounce it.”

The mayor noted that many Calgary street names like Richard Road are regularly mispronounced (it’s French, as in ree-SHARD).

“For us to now say, it’s okay if the Scottish or English names are mispronounced, but we can’t possibly have a First Nations name mispronounced—it’s very problematic for me,” he said.

Some councillors expressed confusion about whether the elders had been accepting of the Medicine Hill name during the earlier consultations. But council twice voted down motions to pause and seek clarification from the elders directly.

“I hope that we’ve come a long way and are able to look at these things more intelligently.”

Paradoxically, at the same council meeting, Blackfoot names for four streets in the area were approved: Saatoohtsi, Na’a, Piita and Natooyii (west, mother earth, eagle and sacred), the first Blackfoot-language street names in the city.

Council also directed city administration to consider bilingual Blackfoot/English signs in the new development. (Trinity Group did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

“I think it’s a great step,” says Deerfoot of the street names and bilingual signs, contrasting it to how his family name was simply appropriated.

“I hope that we’ve come a long way and are able to look at these things more intelligently.”

An exercise in settler humility

Most Calgarians are unfamiliar with Indigenous languages like Blackfoot. It’s also fair to say that it would be challenging for some Calgarians to learn how to pronounce and spell Aiss ka pooma or Saatoohtsi (pronounced sa-toosh).

But the fact that there’s a learning curve does not mean it’s an unreasonable burden, or that there isn’t value in the exercise.

As Canada and Canadians seek to reconcile with Indigenous peoples in a nation-to-nation context, demonstrating a willingness to put in a modest degree of effort to learn about neighbouring cultures can go a long way.

Last year, Edmonton renamed part of a street Maskêkosihk Trail (muss-kay-go-see), a Cree word meaning “people of the land of medicine.”

“[Reconciliation] is more than just apologizing for what residential schools did.”

But our northern neighbours are having the same debate we are, including a councillor arguing against the difficulty of Indigenous names.

Paula Simons, the senator and former Edmonton Journal columnist, noted that Edmonton has readily adapted to many non-English names, from politicians named Lukaszuk to hockey stars named Draisaitl.

Moreover, the effort required is indeed valuable in itself.

“Learning to say the names — even, or especially, if we have to stop to make an effort — should remind just whose ancestral land we’re on,” Simons wrote in 2016. “It’s a good exercise in settler humility.”

Or, as Littlelight observed more bluntly: “You’re calling your society kind of idiotic if you’re saying they can’t say a Blackfoot word.”

Chief Crowchild prefers to focus on his grandfather’s approach of building cultural bridges, though he acknowledges it’s not easy.

“[Reconciliation] is more than just apologizing for what residential schools did, or what colonization did,” he said. “It’s actually quite painful for a lot of people.”

The road ahead

Given these conflicts over roads and development, it’s hard to imagine the city changing its name, as the Stoneys and Piikani requested.

But what if we did? What if Calgary was still Calgary, but also Mohkinstsis (Blackfoot), and Wichispa Oyade (Nakoda), and Guts’ists’i (Tsuut’ina)—officially?

“Learning to say the names… should remind just whose ancestral land we’re on.”

What if those words were used on signage alongside “Calgary,” or promoted through city marketing? What if, instead of drivers encountering signs proclaiming “Be Part of the Energy” upon entering the city, they were welcomed with the names for this place that have survived hundreds and thousands of years?

Some might say such things don’t matter. But names do matter. They contain stories within them, reflecting something about us and our values.

“In any culture, names are very important,” said Treffrey Deerfoot.

“These places all had names for a long time before [settlers arrived].”

Taylor Lambert is a Calgary writer and the author of Darwin's Moving, which won the 2018 City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize.

If you value independent Calgary journalism, please sign up as a monthly supporter of The Sprawl. We're crowdfunded, ad-free and made in Calgary. Join the 550+ Calgarians who support The Sprawl!

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!