Cheyenne Raweater shares a laugh while on patrol.

‘We see you’: On patrol with Bear Clan

Humanizing instead of criminalizing.

Text by TAYLOR LAMBERT

Photos by ONYIE EKENE-OBI

Below the Good Neighbour shop in downtown Calgary lies the Bear Clan den. It’s a humble gathering space, with an old couch and some folding tables, but Bear Clan isn’t about appearance. It’s about results.

It’s Friday night, and when I arrive, a handful of volunteers are already there. Every week the group walks the streets handing out food, supplies and naloxone to anyone. There is no means test, no restrictions and no judgment. The den is where the preparation happens.

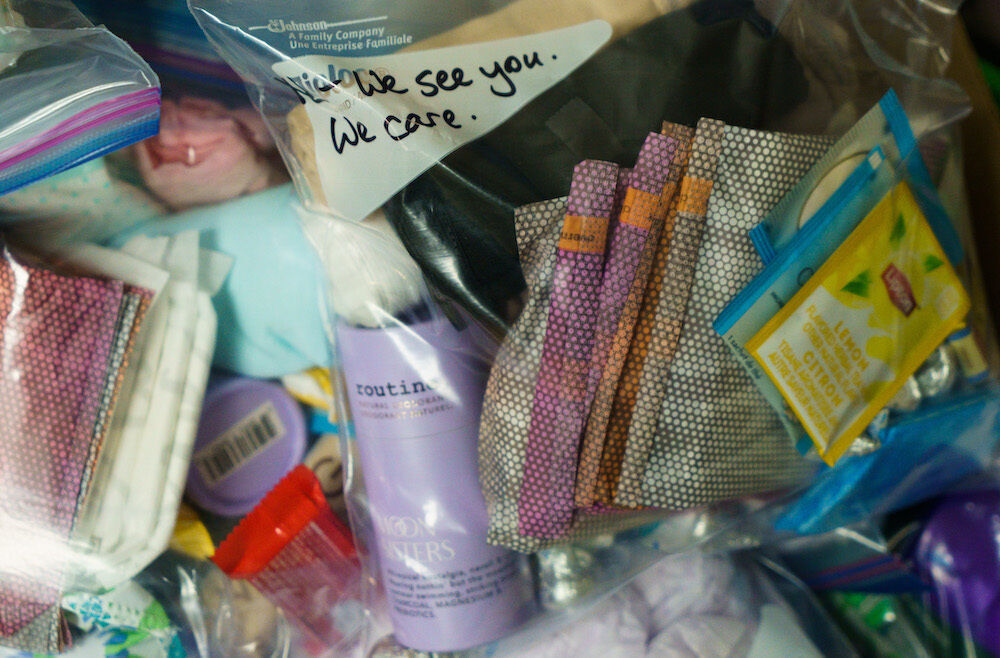

I assemble lunches with other volunteers. Sandwiches are added to bags with mandarin oranges, bottled water, juice boxes, bags of chips and packaged cookies. It’s assembly-line work, a flurry of movement that ends with a few hundred tied plastic bags in wagons and large bins.

Then someone brings in two large, grease-stained cardboard boxes: frybread, which Mamacita and a few other volunteers have made, and which will be handed out tonight.

Mamacita is what everyone calls Yvonne Henderson, one of the co-founders of the Calgary chapter of Bear Clan. It’s an Indigenous-led grassroots initiative intended, in part, to reclaim the community’s position between the police and vulnerable citizens, including drug users and unhoused people.

The original Bear Clan began in Winnipeg in 1992, but it had been on hiatus for some time when, after the murder of Tina Fontaine in 2014, it returned to the streets. The Calgary chapter was founded in 2019 by seven people. Some are no longer involved, but Mamacita represents the heart and soul of the group. Her voice and laugh and energy can fill any room. Today, though, she is tired and worn out, and she holds court while sitting on a couch.

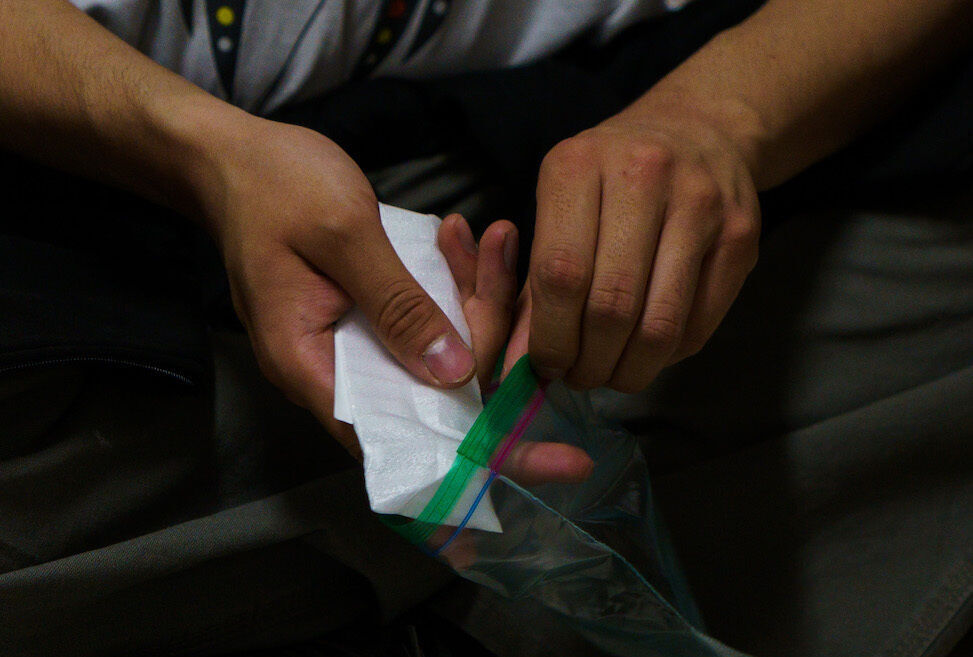

Meanwhile, other volunteers prepare the two harm-reduction backpacks with clean and safe supplies that people using various drugs might need: sharps (needles), bubbles (glass pipes for smoking), straight glass pipes, aluminum foil, along with as many naloxone kits and nasal sprays as can fit. Moon bags are packaged, which include things like tampons and pads, chocolate, and underwear.

Once the prep work is done, everyone gravitates to the main room, where Mamacita tells us about the frybread, or bannock, and its colonial history. More people arrive, including one first-timer. Everyone has to sign in, and the new person is given a waiver to sign.

'We offer compassion'

The smudge bowl is brought around to each person, a cleansing ritual used by the Blackfoot and many North American Indigenous cultures to purge negativity and purify an individual. Marlen, a volunteer familiar to most regulars, gives the opening talk at Mamacita’s behest.

The worst can and does happen on patrols. Marlen asks for a show of hands of who has their naloxone training. A half-dozen arms are raised. How about first aid? There are a few.

“When we meet people on the street, we just want to meet them where they are at that time. We offer compassion, ask how they’re doing,” says Marlen.

Marlen goes over the usual items that get said every week both as a reminder and for anyone on their first patrol—a list that has been refined through the group’s experience.

Don’t wander off by yourself; if you’re going off to help someone, tell a leader and don’t go alone. If someone has their jacket or blanket over their head, don’t approach—they’re probably using. Don’t use the word “food,” which is a street term for drugs; better to say, “I have a gift for you,” or ask if they’re hungry. If you see a discarded needle, call out “Sharp!” and point to it so someone can pick it up. If you don’t know how to deal with an overdose, you’re not expected to.

Mamacita interjects.

“Last week, we had a lot of overdoses,” she says. “There’s a lot of bad product out there.”

Sometimes the patrol encounters drug poisonings—a term some prefer to “overdose,” not only for its comparative neutrality (“overdose” can be interpreted as assigning blame to the user) but because only medical tests could tell whether a reaction was from too high of a dose or an unknown substance cut into street drugs—or something else entirely.

Last week, a volunteer was attempting to help a man who appeared to be overdosing when she was crowded by the man's friend, disrupting her potentially lifesaving efforts. The friend even stabbed the man with a naloxone needle at one point, believing they were helping.

“Nobody stepped in,” says Mamacita. “Everybody stood by and watched that happen.” She reiterates that, in a crisis, volunteers need to help create space around the situation; designated roles on each team are suggested.

Something Mamacita often tells the group is that, while naloxone might save a life, everyone carries medicine within them. Offering kindness, compassion, a friendly response, a joke, or just letting someone feel seen and respected has its own healing power. For vulnerable people ground down by the system and vilified by society, it can make all the difference in the world.

Walking the patrol

We haul the loaded wagons upstairs to the street. After a long wait for everyone to get organized, we depart.

The group takes the usual route, walking to city hall and catching the train to 7th Street S.W. The walk is slower than usual, as people call out “sharp!” to notify that a discarded syringe needs to be safely picked up. By the time we near City Hall station, only a few blocks away, we’ve met more than a dozen people and handed out many lunches and supplies.

Two young people approach and ask for sharps and bubbles. We hand them lunches while the supplies are retrieved. Like most people the patrol encounters, they are friendly, both of them recognizing the people in hi-vis vests and Bear Clan patches as allies.

“It’s my 28th birthday, yesterday,” one of them tells us. We wish a cheerful happy birthday, and they smile as we cross the street.

The train is fairly busy for a Friday night; most people look like they are coming from work rather than going out on the town. We disembark at 7 Street S.W, and spot the flashing lights of an EMS SUV across the street. Taylor McNallie is there with EMTs attending to a man sitting on the ground.

McNallie is one of the city’s highest-profile critics of the police. Her Twitter account and other public statements are provocative and confrontational, expressing a deep-seated conviction rooted in history, observation and personal experience that the police, as an institution, serve to reinforce white supremacy and inequality. When she spoke at a recent police commission meeting, she cited a litany of quarrels—including her being personally targeted on Twitter by chief Mark Neufeld—before stating that “everyone in this room can go fuck themselves.”

She and Mamacita stay with the man and EMTs and tell the rest of us to keep moving. We gather as usual at the convenience store at 8th Street and 7th Avenue SW, which still gets called “Crackmacs” even though it’s now a Circle K. It’s a high-traffic area, and frequently a gathering spot for people who might need our support. We hand out lunches, harm reduction supplies, cigarettes and bus tickets. Some volunteers smoke cigarettes or go buy coffee and snacks. The mobile unit arrives and we replenish our wagons.

McNallie and Mamacita catch up to us; even after an ambulance arrived, the EMTs were reluctant to drive the man the few blocks to Sheldon Chumir medical centre, though they eventually did.

It’s now dusk and time to move again. We split into two teams, each with supplies and people with first aid and naloxone training. Each team takes one side of 7th Avenue and we walk east along the train line.

I’m with McNallie on the north side, and she’s brought a portable speaker that starts pumping out music. The volunteers start singing and dancing as we walk.

We arrive at 4th Street S.W. station, which adjoins a plaza and the park across from the courthouse. It’s dark now, but the weather is pleasant, and the area is lively with groups of people, some of whom are sitting in circles on the ground next to bags and shopping carts. Two people are sitting behind a low concrete wall. A few people are using drugs.

The patrol is recognized and welcomed. We offer lunches and supplies and chat with people as the music continues. McNallie converses with a man on the ground who has a collection of items strewn around him: a coffee maker, a keyboard, parts from a turntable. The collective mood is friendly, even joyful. It feels like a community.

The people Bear Clan directly interacts with aren’t the only ones who have taken notice of the group. The Calgary chapter has been (briefly) mentioned in a peer-reviewed journal, and the Bear Clan model is discussed in a business and marketing textbook as a positive example of deindividuation and accountability in groups.

“The Bear Clan patrol groups demonstrate how when a group of like-minded individuals come together to address common concerns, their camaraderie provides a stronger sense of purpose and energy, possibly more so than when individuals act alone,” writes Andrea Niosi in Introduction to Consumer Behaviour.

The collective mood is friendly, even joyful. It feels like a community.

Bear Clan appears in government papers as well—a 2019 report from the federal Standing Committee on Health begins with a brief narrative scene of the committee members out on patrol with Bear Clan in Winnipeg.

The Winnipeg chapter, aside from being the originators of Bear Clan, is probably also the most celebrated and well-funded, winning awards from the business community and a local Islamic association, and receiving hundreds of thousands of dollars in government funding.

Much of that funding, however, is directed via the police. Bear Clan Calgary does a lot with far more modest means, all of which comes via donations from the community.

Bear Clan doesn’t trust the police to help people who are Indigenous, Black, vulnerable, unhoused—a position informed by statistics, history and experience. If an ambulance is required, the 9-1-1 operator is requested to not send police. If police or security guards are seen approaching people, Bear Clan will intervene to say, “Let us handle this.” It’s the same logic behind redirecting police funding to community- and health care-based resources, but driven from the bottom-up, rather than top-down.

Bear Clan is what happens when the community tries to take back power.

A confrontation in the park

Later in the evening, the patrol spots a group of bike cops across the street in the park adjacent to Olympic Plaza. They appear to be talking to the other half of our group. At McNallie’s direction, the speaker blasts out NWA’s Fuck Tha Police, then pig noises from a YouTube video. The cops give no sign of noticing the trolling; their interaction with the Bear Clan volunteers continues. After watching a while, McNallie crosses the street to see what’s going on. I follow, as do a couple others.

A man is sitting in the park with a shopping cart. Apparently he is waiting for his daughter, who is having her period and has gone to find a bathroom—one of the frequent obstacles to basic necessities faced by unhoused people. There is a bylaw that closes the park at 11 p.m. A discussion is underway between the five cops trying to eject the man from the park and the Bear Clan volunteers, particularly McNallie and Mamacita. They say the cops are harassing the man, that he is not bothering anyone, that he is a vulnerable Indigenous person on treaty land with few good options.

It soon becomes an argument, as one cop in particular is determined to push McNallie’s buttons. They all know who she is. They also know that they are in a position of significant power, choosing to argue for sport while secure in the fact that, as the police, they can win any argument at any time. “You’re harassing a person—” McNallie is cut off by the cop.

“No, no, see, you’re ramping up the situation. I was very calm.”

“The very existence of you fucking ramps up everything! I’ve had enough garbage with you guys to know that I don’t need to have civil conversations with you. Because you’re fucking trash.”

“Every one of us is, yeah?”

“Every single fucking one of you.”

Mamacita steps forward and interjects. “You just have to have the last word,” she says to the cop. McNallie spies something on his uniform and steps towards him, gesturing to it.

“You’re wearing a fucking thin blue line patch, yeah, you’re fucking trash!”

“Yeah, I know. You should just make a choice to not be a piece of shit and take it off.”

“Very nice. You’re a very nice person.”

“I don’t need to be nice,” says McNallie.

Mamacita steps in again. “Why do you have to have the last word?” she asks the cop. “You could just leave it, do your job, just bike away and say that we’ve got the situation.”

The cop’s tone becomes more condescending. “You know what, ma’am? I would love to. But—”

She cuts him off. “You would love to, but your ego is talking.”

For some, the police represent safety and serve as society’s protectors. For others, the police represent danger and serve as society’s enforcers.

At its heart, this disconnect is rooted in different conceptions and experiences of society: Canada as a place of relative equality and opportunity; Canada as a place with moral, spiritual and legal roots in white supremacy.

Those roots, long disguised for the comfort of white Canadians, have in recent years been exposed and highlighted in newly prominent ways. That the residential schools, slavery, internment camps, and overt racial restrictions on immigration are gone does not erase their legacies: inter-generational trauma; cycles of addiction and abuse; disrupted lineages of culture, tradition and family; and a society that still deeply wants to believe it is good and fair, just as it did a century or two ago.

Hence the argument that the goodness or badness of an individual cop is irrelevant: Policing itself, including transit cops and private security guards, is the problem because of who and what it is protecting.

Eventually, the patrol slowly leaves with the man; his daughter still hasn’t returned. The cops stay in the park. Back across the street, Taylor tells the others what happened.

“Man has no home and you’re kicking him out of the park,” she says incredulously. “Get fucked.”

The patrol is all but over. We walk back to the den to return the wagons and vests.

There’s a sense of mixed feelings: the empowerment of directly helping someone get through today, offset by the knowledge that the forces aligned against them will still be there tomorrow.

Still—for today, it’s something.

Taylor Lambert is a freelance journalist based in Calgary. Read more of his work at taylorlambert.ca.

Onyie Ekene-Obi is a Calgary-based photographer who is originally from Nigeria. She has a master’s degree in international relations and diplomacy, and will soon be a graduate of SAIT's photojournalism program. See more of her work at throughonyieslens.com.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!