Photo: Jeremy Klaszus

The rumble over rezoning in Calgary

What can we learn from Inglewood?

Sprawlcast is Calgary’s in-depth municipal podcast. Made in collaboration with CJSW 90.9 FM, it’s a show for curious Calgarians who want more than the daily news grind.

If you value in-depth Calgary journalism, support The Sprawl so we can do more stories like this one!

COUNCILLOR GIAN-CARLO CARRA: It really boils down to a question of do you believe that the single-detached house is sacrosanct? Or do you believe that the single-detached house lives well with semi-detached houses and rowhouses?

FRANCISCO ALANIZ URIBE: It is a necessary change if we want to shift and not continue to be a sprawling city.

SHIRLEY-ANNE REUBEN: It's a blanket vision of ‘we want more housing.’ And yes, we do, but how are you going to achieve the affordable part?

JEREMY KLASZUS (HOST): It’s the eternal question in Calgary. How to stop the city from sprawling, and shift growth into established neighbourhoods.

COUNCILLOR CARRA: The reality is that—and this is a conversation that I’ve had with my constituents since I first got elected—the only thing I can guarantee you about your community is that it’s changing.

KLASZUS: This is Ward 9 Councillor Gian-Carlo Carra, who’s been on council since 2010.

COUNCILLOR CARRA: And so the idea is that you’ve got three choices. You can sit back, relax, and see what happens. You can engage in the fool’s errand of trying to prevent change. Or you can sit down with everyone who needs to be around the table and have really thoughtful conversations about where have we come from, where are we at, and where do we want to go?

KLASZUS: Who should decide the answers to those questions, however, is a matter of contention. Especially as city council prepares to vote on citywide blanket rezoning, also known as inclusionary zoning or upzoning. It’s an element of the city’s housing strategy, which council approved in September of 2023.

Citywide rezoning would make gentle density like rowhouses a discretionary use across the city, which means they would no longer require a public hearing and council approval (but builders would still need to apply for development permits).

KLASZUS: It’s an effort to build much-needed housing supply across this city. And this has sparked lively discussion on and off council. In March, council debated whether or not to put the issue to a plebiscite. Let’s listen in. We’ll hear Councillors Sonya Sharp, Kourtney Penner, Terry Wong and Courtney Walcott.

COUNCILLOR SONYA SHARP: None of you could admit that you campaigned on removing the public hearing process from increasing density.

COUNCILLOR KOURTNEY PENNER: I may not have explicitly campaigned on a base rezoning of R-CG. But I absolutely did say over and over again that placing people next to the things that already exist in communities and that it was people that mattered—I did campaign on that.

COUNCILLOR TERRY WONG: Calgarians want us to build a future for their families. But they don't want to do it in a rushed sort of way. They want us to be able to be meaningful in our engagement—listen in a meaningful way.

COUNCILLOR COURTNEY WALCOTT: We at some point have to make a decision. To kick this to a plebiscite in the next election benefits those who do want to run on opposition to change in your communities. That is a political choice. That is not a choice that helps Calgarians. That is not a choice that buids housing. That is not a choice that helps our affordability. And that is not a choice that helps our competitive edge. That is a choice that helps the selfish few.

KLASZUS: Council voted against putting the matter to a plebiscite. But the entire issue raises questions beyond this one specific vote.

When it comes to neighbourhood change, should communities set their own direction? Should city hall impose it from the top down? Or is there a role for both—especially given the housing and climate challenges we’re facing as a city?

In this episode, we’re going to dig into those questions. And we’re going to do this by visiting an established neighbourhood. In fact, it’s the oldest neighbourhood in the city. Let’s go to Inglewood.

Inglewood and the 'everyman' planner

Ten years ago, Inglewood was chosen as Canada’s greatest neighbourhood in a contest of Canadian urban planners. And today, it’s one of the most desirable neighbourhoods in the city, with its industrial roots, its close proximity to downtown and the river, and its mix of shops and restaurants on 9th Avenue. Its population is growing.

But Inglewood wasn’t always a popular place. In the 1960s, Inglewood was down and out. Its population was in decline. It was viewed disdainfully by the rest of the city. And it was under direct threat from engineers at Calgary city hall, who wanted to build a freeway through the community.

SHIRLEY-ANNE REUBEN: It was considered East Calgary, and not a place you would send your children, and it was unsafe. But the reality was the community itself was very safe.

KLASZUS: This is Shirley-anne Reuben. She’s lived in Inglewood since the early 1980s, and she’s the founding director of the Jack Long Foundation, an organization focused on affordable housing for seniors.

REUBEN: Inglewood always had, you know, it could be the million dollar house next door to something that hasn't been updated since 1940.

KLASZUS: I first spoke with Reuben in 2006 for a story about Inglewood and affordable housing that I wrote for Alberta Views magazine. And it’s funny—you could reprint a lot of that article today. I wrote about how 9th Avenue was becoming increasingly gentrified. And how living in the neighbourhood was becoming increasingly unaffordable for many, including the working-class residents who made Inglewood what it was.

REUBEN: It’s become very, very upscale. We always joke that, my goodness, don’t know if we’d be able to afford to live here if we were buying today.

Inglewood always had… it could be the million dollar house next door to something that hasn’t been updated since 1940.

KLASZUS: Through Reuben, I encountered the work of Jack Long. Jack Long was an Inglewood resident, an architect and a planner. In the 1960s, he designed the Centennial Planetarium building, where Contemporary Calgary is today. And in the early 1980s he served a term as a Calgary city councillor.

But it’s what he did between those accomplishments that I find particularly interesting. In 1973, while in his 40s, Jack Long wrote his master’s thesis about community-driven planning. And the title of his thesis says it all. It was called “Everyman the Planner.”

The gist of his work was that ordinary citizens have “a right to plan their environment that is at least as valid as the planner’s right to do it” for them. And this caught my imagination—the idea that community residents, not bureaucrats, could plan their own neighbourhoods, based on their knowledge and experience of the place.

And he worked out his ideas in his own neighbourhood of Inglewood.

REUBEN: So when you talk to people who grew up there, what they talk about is very Rockwellian. I mean, it’s quite interesting—they have a swimming hole built, the train conductor picks them up and takes them home. So Jack capitalized on that value, and people know best. I think what he was going at by that is, you know what your community is. And yes, we are protective and sometimes we don’t like change—and I think that’s true for everybody. But I think if people have a conversation, if they feel that they are being heard, and if they can see something that might lead to something better, they will work with you.

KLASZUS: Councillor Carra calls Jack Long the Jane Jacobs of Inglewood, referring to the influential urban activist and author.

COUNCILLOR CARRA: Inglewood is a place that experienced what Jane Jacobs experienced when she wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities as the theory behind the fight that she was part of leading to save Lower Manhattan, and Greenwich Village specifically, from destruction at the hands of a top-down autocratic bureaucrat, Robert Moses. And most places in North America that fought that fight in that era—late 50s, early 60s—lost.

But under Jane Jacobs’ leadership, Greenwich Village prevailed, and the fate of the entirety of New York City was shifted.

In Calgary, in Inglewood, with the leadership of Jack Long, Inglewood prevailed. And human-scaled urbanism prevailed in the face of the bulldozers of automobility, and it changed the fate of this city in a very significant way.

KLASZUS: Jack Long and his neighbours hashed out a design brief to guide future redevelopment in their community. And they didn’t just decide what they wanted to keep out. They also articulated what they wanted to let in. This included projects like the Rhubarb Patch—seniors housing that would let residents stay in the neighbourhood as they aged.

REUBEN: Again, it was born from a sense of community and a sense of respecting the people that lived in there. They were not some sort of social project, right? It wasn’t them; it was 'our people need housing.' And that was because it was a working class community in the first place.

KLASZUS: Reuben was president of the Inglewood Community Association in the 1990s.

REUBEN: When I was with the community association, and we had all of those pressures for development, we didn't get everything we wanted. We worked hard—and often, it wasn't really the development we wanted. But what I would say to people is, you know what? We got way better [than if we hadn’t provided input], and understand that you're going to have 300 nice new neighbors. And once you get to know them, you're not going to see the building. And that's the truth, right?

But if you build things so that it causes this kind of clash, and it kind of feels like an invasion of the neighborhood, it's much harder to create those ties. Because people may not feel welcome. And people may not be welcoming.

KLASZUS: Reuben worked with Jack Long on community projects until his death in 2001.

REUBEN: There are many people of the elder generation that will tell you Jack changed Inglewood. But I have told them: it's not Jack that changed the neighborhood. You did. You did, with him.

The 'underlying friction' as neighbourhoods change

KLASZUS: If you walk around Inglewood today, you’ll hear a lot of construction. You’ll see the old and the new, side by side. Along 9th Avenue, there’s been lots of local opposition to proposals for high rises that are 10 storeys and taller. And just to be clear, these have nothing to do with citywide rezoning as proposed by city hall. That’s about rowhouses on residential streets. But towers pitched for 9th Avenue have provoked a strong local response.

BRUCE MACDONNELL: There's still a lot of resistance in the community to going up above that six story [height].

KLASZUS: This is Bruce MacDonnell, the planning director for the Inglewood Community Association. He gave me a walking tour around the neighbourhood—including down 9th Avenue.

MACDONNELL: I think that's one of the kind of underlying friction points to the community is rate of change. Rate of change in height, rate of change of density…

One of the things it's kind of hard in the current discussions is if you if you disagree with 10 storeys, there's a lot of voices that will paint you as being wrong or or bad. As opposed to—hey, what do you prefer?

KLASZUS: But he points out wins, too, like what’s happening in the building where Trail Appliances used to be.

MACDONNELL: This place is kind of cool, because while we're waiting for the builder to come with a development permit, they've put in small shops.

KLASZUS: While most of the headline-grabbing changes are happening along 9th Avenue, Inglewood is changing on its residential streets too, as more infill development goes in. This is something that’s happening across inner-city communities.

Take 14th Street, for example. If you’ve been in Inglewood, you might have seen an old white barn, built in 1909. Well, now townhouses are going up right next door. And they’re going to include the old barn and use it as live/work space and a parking garage. It’s the kind of ground-oriented rowhousing that city hall wants to make a discretionary use citywide.

MACDONNELL: The developer came to us early in the planning. He was really forthright from everything from what trees does he have to take down, how many units does he have to get on to make it viable to save the white barn? What can he and can’t he do with setbacks? And that kind of open communication really helped.

KLASZUS: MacDonnell says it’s an example of redevelopment done right. But he says that’s not always the case.

MACDONNELL: Areas we really want to improve is when we find that there’s been more opaque discussions between a builder with a proposal and planners and perhaps council, and they come to us when it’s kind of fixed. And we’ve noticed in those cases, our input really doesn’t change the substance of the development and the size, and that’s disheartening.

KLASZUS: So what does a community truly want? That’s a tricky question, as there are a range of views in any neighbourhood.

MACDONNELL: We have community members who come to me and say, I’ve got an application for a tall building next to me, and I don’t care. We have community members who come and say, five doors down they’re putting an R-CG in, and I don’t like it.

There’s a sixplex being built right around the corner from my house. There is no chance in the world that those are going to be affordable units.

KLASZUS: The Inglewood Community Association has signed on to a joint letter from numerous community associations that are calling on city council to reject citywide rezoning.

MACDONNELL: We we hear the proposal that it's going to be a slow change. When you're in a neighborhood that’s as desirable as Inglewood, we think that rate of change is going to be faster.

KLASZUS: Shirley-anne Reuben has been working on and advocating for affordable housing for decades. And over the years she’s seen city hall roll out many plans for the city’s future.

REUBEN: They all get forgotten, and it's basically the same study. And I realize times change and the context is different in terms of where’s the city’s at with their development needs, all of those things, and population needs and stuff. But I think this blanket zoning takes away any type of community context...

There's a sixplex being built right around the corner from my house. There is no chance in the world that those are going to be affordable units. It's just not going to happen.

City hall's rationale for blanket rezoning

KLASZUS: Let’s dig into that, and zoom out from Inglewood a bit.

JOSH WHITE: We hear a lot that ‘well, this will not be a civil silver bullet to affordability, this is not about affordable housing’—that capital-A, capital-H, subsidized Affordable Housing. And it's not.

KLASZUS: This is Josh White, the City of Calgary’s planning director.

WHITE: The housing strategy is about the entirety of the housing continuum. That's not why it's just one action to do a rezoning. It's about 90-plus actions to deal with everything from sheltering to deeply subsidized housing to every part of the market continuum.

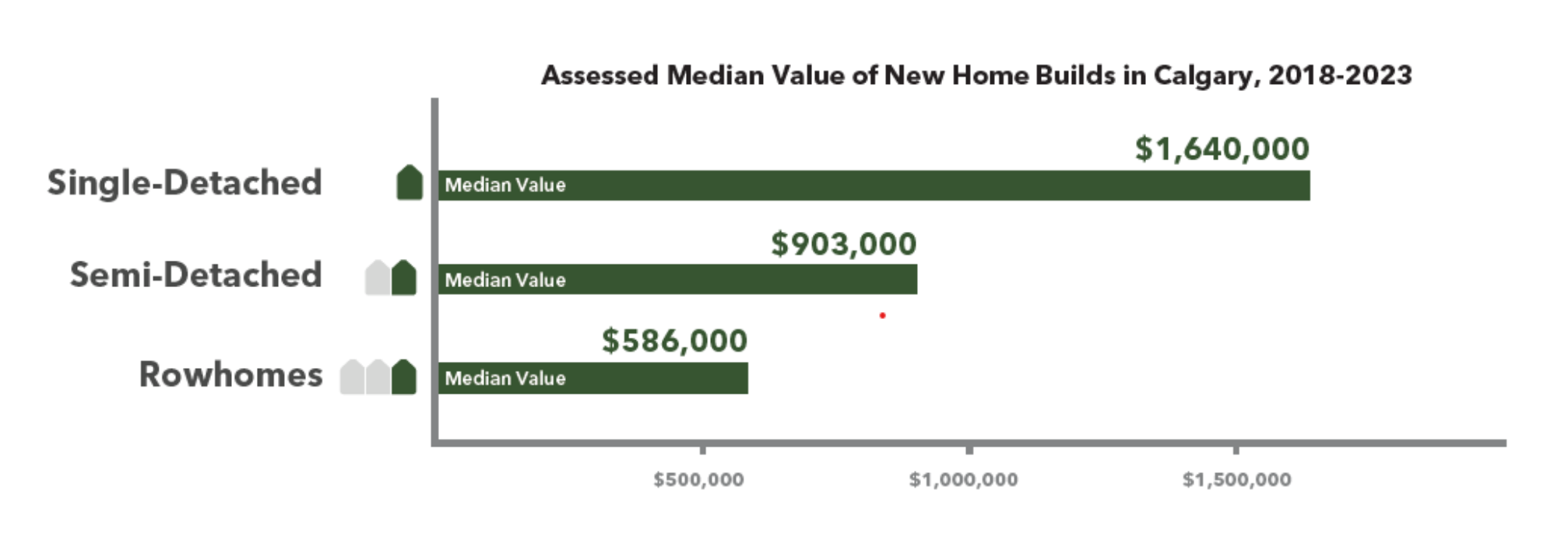

And this proposal around rezoning is very much about the middle of that continuum. It’s trying to solve a specific problem that we have in our housing, which is that we have a big gulf in our housing market between, for example, apartment dwellings, and single and semi-detached housing.

There's a big gap, both in form and price and level of affordability, that most cities are experiencing. That's why they call it the ‘missing middle.’ It's not just about the form, it's about the level of affordability it provides.

KLASZUS: At the time Jack Long articulated his ideas about the “everyman” planner, Calgary had lots of room to grow at the periphery, or so went the thinking of the day. But that’s changed, which is part of why citywide rezoning is on the table. For decades, city hall has recognized that sprawl is financially and environmentally unsustainable.

With this in mind, in 2009, council passed a plan to shift half of all new growth into established neighbourhoods—places like Inglewood, but also neighbourhoods further out that have seen their populations decline.

It’s trying to solve a specific problem… which is that we have a big gulf in our housing market.

FRANCISCO ALANIZ URIBE: What is really valuable about across-the-city rezoning is that you're distributing the opportunity for development across the whole city.

KLASZUS: This is Francisco Alaniz Uribe, an associate professor in the U of C’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape.

ALANIZ URIBE: All the previous measures have been, okay, let's have some growth inward—but just in a few places. In some corridors, in some nodes, close to LRT stations. And that all seemed to be very reasonable. But what doesn't really work—and we have seen it over more than a decade—is that doesn't provide enough diversity. In the end, it doesn't open up enough land for growth.

I live in a single-family bungalow in a community that is mainly single-family homes. I chose to live there. It took me a while to be able to find a place where I could afford, but I chose to live there because it was close to the university, my place of employment, and I didn’t want to have these long commutes.

I think that what everybody in Calgary needs to reflect on is that this change is necessary to make land available for others. We who are already settled in these neighbourhoods might see it as a threat, as change that you’re not comfortable with. But we have seen over and over that future generations are having less and less access to land, and to owning a home. And unless we do something like this, it’s not going to be possible for them.

I think that what everybody in Calgary needs to reflect on is that this change is necessary to make land available for others.

WHITE: It’s possible that we could have grown by over 60,000 people in the last 12 months. Just think of the scale of that. That is immense. That’s a plane full of people to the city of Calgary—just the city of Calgary, let alone the region, every single day.

KLASZUS: In May, city planning director Josh White is moving west to become the City of Vancouver’s general manager of planning. I wanted to catch him before he leaves to ask him about how the different pieces of the planning puzzle fit together in Calgary, or don’t.

WHITE: There’s always, I think, a healthy tension, a healthy push and pull between adjudicating what should be considered at the local scale, and what should be considered at the city-wide scale.

KLASZUS: That’s something that has evolved over the years.

WHITE: For a long time, our approach was to go very, very fine grain, very community by community, whether that community was very small or very big. And we’d go through a long process of engagement, and come up with plans at an individual community level. Now, there are plusses to that, but there are also some minuses in that. We have 200 communities, and it takes a long time to go through all 200 communities at a community by community basis.

And so we’ve started to evolve that approach through things like multi-community plans that still is very much about the local context, but is a more methodical and I think a more productive way to do local area planning.

KLASZUS: Another major planning piece in recent years was the Guidebook for Great Communities, which didn’t get enough support on council in 2021.

We are about to look at the nuclear option of universal upzoning largely because the Guidebook for Great Communities for Everyone got stalled out politically.

WHITE: What that exercise really was about was saying: Okay, here's a set of rules that we can apply to different parts of the city. And so when we go to do a local area plan, we don't just have to copy and paste the same policy everywhere if there's some value to having some consistency across communities. But what we did hear, and what we've learned through that experience of the Guidebook, is that people wanted to say no, there’s a bit too much maybe homogeneity to some of those policies. We actually want to have some of those conversations more at the local level.

KLASZUS: But White says a citywide approach is appropriate for some changes.

WHITE: The Rezoning for Housing change for the base residential zoning—people characterize it as ‘blanket rezoning.’ Well when was the last time we talked about blanket rezoning? It was secondary suites.

KLASZUS: White is referring to 2018, when council made basement suites a discretionary use. Before that, council had to vote on each individual secondary suite.

WHITE: In the secondary suite debate our position was: It’s appropriate everywhere. There’s nowhere where it’s not appropriate. So therefore, it’s not the right approach to go community by community and say, should it be on this street or this street? We believe that fundamentally, secondary suites should be allowed in every context of the city. That change was made.

A lot of the same types of concerns around you know, whether it’s renters or parking, it’s a lot of the same type of conversation that you had there. And guess what? That change was made. It was made through a lot of public conversation at the citywide level. The change was made, and I don’t know if anyone would suggest that we should go back on that change.

It was appropriate to make that kind of change at the citywide level, we felt, and I think that’s proving to be true because we’ve been able to very quickly legalize thousands and thousands of suites each year.

It’s about building in Acadia and Bowness and Dalhousie and Mayland Heights. And land costs in those areas are less.

Right now, we have a regulatory environment around rowhousing where you have to go through a rezoning. So what builders are doing is they're clustering in places where there's the least market risk, and that's the premium neighborhoods. It is neighborhoods like Inglewood. It is neighborhoods like Altadore. It is neighborhoods like West Hillhurst where the land is more expensive, but there's a proven and tested market.

And so what we think this change will allow is by taking away some of that regulatory time and risk and cost, and allowing more neighborhoods to have that opportunity, that peanut butter gets spread way more across a larger geography of the city. So it's not just about building in Altadore or Inglewood. It’s about building in Acadia and Bowness and Dalhousie and Mayland Heights. And land costs in those areas are less.

What we know about rowhouses is that the cost of them tends to be about equal to the land costs. So if you're buying a $750,000 parcel of land, a 50-foot lot in Altadore, those four units are going to be about that price. They're going to be about $750,000. But if you're opening up opportunity in areas where land is $500,000, that means those units will also be about $500,000.

That's how the arithmetic works around this type of dwelling. There's an inflection point where those four units that replaced the one are about the same cost as the land input. And that provides that relative affordability.

'The most important question is: Who acts?'

KLASZUS: Jack Long believed a community should flesh out its own definition, its own sense of self, and its values—a constant process. He believed community venting and lamenting was inevitable. But then the task is to redirect this energy “into more positive avenues.”

How would you know you’re on the right track? “Each time the community acts, the most important question is: ‘Who acts?’” Long writes. If the answer each time includes more people, then the process is evolving into “genuine community participatory planning.” If it’s just a dwindling few, it’s not.

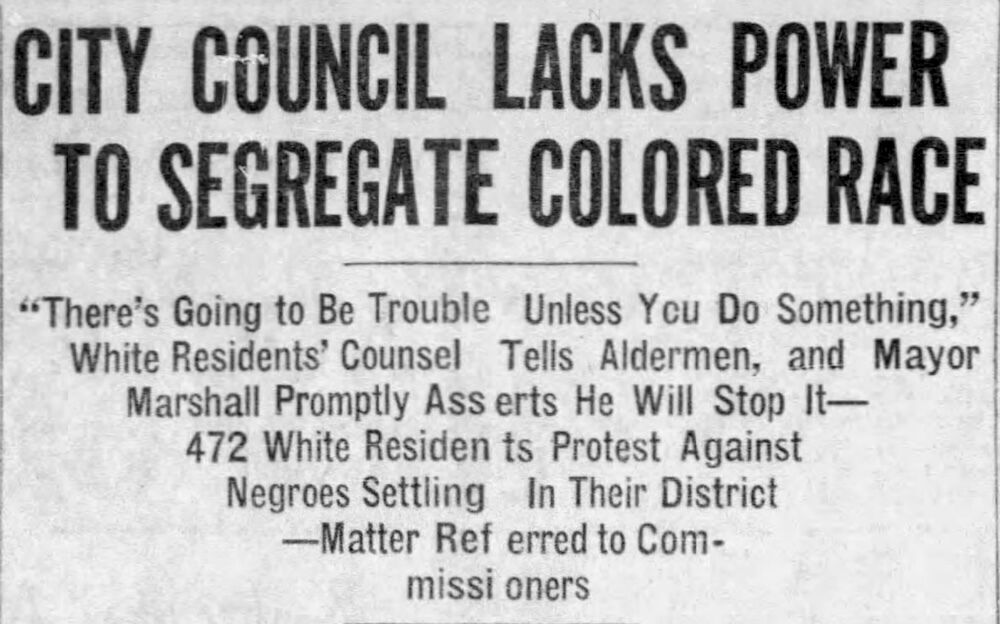

There are obvious limits to this idea. Long said the “everyman” is just as susceptible to powerplaying, envy, distrust and short-sightedness as the bureaucrats and politicians. And history shows us that just because a group of people in a certain place form a consensus, that doesn’t make it a good idea. Our own local history shows this.

For example, in 1920, just west of Inglewood in Victoria Park, white Calgarians fought city hall in an effort to keep black Calgarians out of the neighbourhood.

“The application is to pass a bylaw preventing a certain class of people from living in a certain locality,” said the city solicitor of the time. “Clearly, we cannot do that.”

History shows us that just because a group of people in a certain place form a consensus, that doesn’t make it a good idea.

KLASZUS: I spoke with local historian and author Cheryl Foggo about this in 2020.

CHERYL FOGGO: They first of all wanted to take people's homes away from them and send them away. They wanted them removed. They also wanted to prevent any further infiltration, as they thought of it, of Blacks into the community. So about 75% of people who were living in Victoria Park at that time signed a petition.

KLASZUS: Those white residents of Victoria Park were planning their own community. They had a large grassroots consensus. But that didn’t make it a noble idea.

KLASZUS: In North America, exclusionary zoning is a tool that’s been used, directly and indirectly, to keep certain people out of certain neighbourhoods. Here’s Councillor Courtney Walcott.

WALCOTT: Zoning in North America was about keeping black people, Jewish people, Asians, and people of diverse sexual orientation out of communities, through legal means on the zoning. It was compounded with discriminatory mortgage practices that segregated communities.

When you take away all of the more explicit discriminatory aspects of this legislation, what you're left with is a class one. You see, if you're able to control the type of home that can be built in a neighbourhood, by proxy you're also ensuring that the most expensive, or a house of a certain price point, is the only thing that can be built in your neighbourhood.

While many people aren’t arguing anymore for racialized segregation, by nature zoning is in itself class and economic segregation.

WALCOTT: And so while many people aren't arguing anymore for racialized segregation, by nature zoning is in itself class and economic segregation. Because if we know that a single-detached home is the most expensive home, and we are advocating for maintaining neighbourhoods that are entirely built of a form that is unaccessible to most people, then we are economically segregating different classes of people from different communities.

'The conversations in a place like Inglewood are over': Carra

KLASZUS: Let’s go back to Inglewood. Carra was the Inglewood Community Association president before he got elected in 2010. And in that role he helped flesh out a new rendition of Jack Long’s original design brief, focusing on keeping Inglewood a compact urban village.

COUNCILLOR CARRA: We produced the Inglewood design initiative because we came to the realization that fighting one-off battles on individual development proposals was not solving the problem that we wanted to solve. And actually, the fact that people were fighting about things like that was counterproductive. It was counterproductive to the community and our resources. It was counterproductive to the developers who were trying to make money, providing things that the market was demanding. And it was counterproductive for the city that needed a sustainable tax base.

We came to the realization that fighting one-off battles on individual development proposals was not solving the problem that we wanted to solve.

KLASZUS: Since being on council, Carra has found himself at odds with the community association he used to lead.

COUNCILLOR CARRA: [After I was elected], I think everyone I had worked with over for 10 years in Inglewood basically high fived and said ‘Gian-Carlo’s got this,’ and went home to their families after that 10-year campaign of community volunteerism. And a bunch of people who had been sitting on the sideline, gnashing their teeth angrily about all these conversations we were having, ran into the community hall, locked themselves in, and started to fight a rearguard battle against what we had sort of achieved.

KLASZUS: Carra wasn’t just at odds with the community association—but with voters, too. He barely won the 2021 election, which is rare for an incumbent candidate. He only won by 161 votes.

COUNCILLOR CARRA: I think the conversations in a place like Inglewood are over, and you either believe that it is a great neighbourhood, and you are happy to be there, or you feel like it was a great neighbourhood that is being destroyed by all the changes that are being wrought upon it. And we seem to be living in a point of polarization where there’re just those two extremes and nothing in between.

KLASZUS: I asked Bruce MacDonnell of the Inglewood Community Association what he thought of Carra’s take.

MACDONNELL: That’s unfortunate because we count on our elected representatives to speak for us and speak to us. We just spent 45 minutes walking through the neighbourhood looking at successful developments. And we need to have open conversations. There are developers we’ve sat down and had productive conversations with, applications we’ve supported that have gone up—four to six-storey buildings, apartments, front doors with people living in them. And that’s a success story.

That’s unfortunate because we count on our elected representatives to speak for us and speak to us.

KLASZUS: Councillor Carra suggests that in the current climate, a top down approach on rezoning is necessary. He says citywide rezoning is “the single biggest barrier to us getting on to the conversations that matter.”

COUNCILLOR CARRA: What remains now is a profession-wide conversation about whether the Jane Jacobsian and Jack Longian ideal of every person being a planner still applies in an age of increased polarization, of weaponized disinformation.

We are about to look at the nuclear option of universal upzoning largely because the Guidebook for Great Communities for Everyone got stalled out politically. And I remember saying to communities, I was like, ‘If we don’t support this document and local area planning, we’re going to have to achieve necessary outcomes by other means that are much less conversational and thoughtful, and much more brute force.’ And here we are, about to do a universal upzoning.

The silver lining is that if the universal upzoning passes, then that major bone of contention goes away—and maybe we can then come back to the table, and thoughtfully all be planners together.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl. Support The Sprawl's independent journalism today!

CORRECTION: This story originally stated that the townhouses alongside the Stewart Livery Stable in Inglewood are zoned R-CG. In fact, that specific property is zoned as a direct control district (DC), which is a customized land use designation, to preserve the old barn. The Sprawl regrets the error.

Support independent Calgary journalism.

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!