The real costs of Calgary’s new arena deal

Why it’s less transparent — and far more expensive.

Sprawlcast is Calgary’s in-depth municipal podcast. Made in collaboration with CJSW 90.9 FM, it’s a show for curious Calgarians who want more than the daily news grind.

If you value in-depth Calgary journalism, support The Sprawl so we can do more stories like this one!

The short version

- The City of Calgary is putting up $853 million in cash to build a new arena complex in Victoria Park—nearly three times what the previous council committed to in 2019. The Flames are putting up $40 million.

- The Flames will repay $316 million to the city in annual lease payments, but the city won’t recoup this full amount until around 2060.

- City council unanimously approved this expenditure with no public debate on April 25, 2023—including councillors who explicitly campaigned on “no more public dollars for the Flames” (Courtney Walcott) and warned that the Flames’ owners had “railroaded council and will take us for all we’re worth” (Jasmine Mian).

- The Alberta government is contributing up to $300 million for infrastructure upgrades around the new arena, including an underpass beneath the CP train tracks on 6 Street S.E., and the demolition of the Saddledome. The province is also covering half the cost of a $53 million secondary arena that is part of the complex.

- While city admin and councillors have said the deal won’t increase municipal taxes or debt, University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe says this is misleading: “It makes it sound as though it’s a free lunch, which is definitely not the case.”

The long version

MAYOR JYOTI GONDEK: We had a wide range of views on this project, and through civil discourse we arrived not only at a clear decision, but a unanimous decision.

JOHN BEAN (FLAMES CEO): We are trying to get this done for September of 2026.

COUNCILLOR SONYA SHARP: In a time when affordability is top of mind for many Calgarians, this is an important investment in our local economy, our downtown recovery, and our future.

TREVOR TOMBE (ECONOMIST): It’s definitely not a free lunch. There are costs because we’re foregoing the opportunity to use those funds for other purposes.

JEREMY KLASZUS (HOST): “No more public dollars for the Flames.”

It was the summer of 2021, and that was the headline on a campaign post published by Courtney Walcott. He was running for the Ward 8 seat on council at the time and his post called for a pause on the arena deal.

Walcott was tapping into a popular public sentiment: that if billionaires like Flames co-owner Murray Edwards want a new arena for their NHL team, they should pay for it. The cost of the new arena was already escalating from the original $290 million committed by the city in 2019. That deal had the Flames and the city splitting the costs 50/50.

Walcott wrote: “Calgarians deserve the opportunity to weigh in on any further billionaire bailouts by their city council—not just because the Flames’ ownership is asking for more money, more land, and more power, but because Calgarians were never really given the opportunity to weigh in on this deal in the first place. Calgarians know better than to believe that massive public subsidies to private billionaires will revitalize our economy.”

Walcott wasn’t the only councillor who campaigned against public subsidies for the Flames.

Calgarians know better than to believe that massive public subsidies to private billionaires will revitalize our economy.

KLASZUS: Here’s what Ward 3 Councillor Jasmine Mian said in a candidate survey before she was elected in 2021: “I never would have approved the arena deal because if there’s a market for a new Flames arena, the owners could build it themselves. I think they railroaded council and will take us for all we’re worth. Council wanted this project and cut public engagement short to make it happen. If I could go back in time and stop the deal, I would.”

Fast forward a couple years. That deal fell apart at the end of 2021. And in April of 2023, Walcott, Mian and the rest of council voted for a new $1.2 billion deal that saw no public engagement, no debate at council and has an upfront cash cost to the city of $853 million to build the arena. That’s nearly triple what the city put up in the 2019 deal. The Flames, by comparison, are putting up only $40 million up front.

As part of this deal, over $300 million will be repaid by the Flames to the city over 35 years—and we’ll get into that. But it’s not just the numbers that are different this time around.

For the 2019 deal, city hall made the details public before council voted on it. The deal was presented and parsed for hours on the floor of council before it was approved in an 11 to 4 vote. But not this time. This time, the details of the deal were kept under wraps, and the deal was passed at council in just over sixty seconds. And while the previous deal had council critics, this council passed the new deal unanimously, with assurances that this will contribute to a broader revitalization in Victoria Park.

To build the arena, the city is putting up $853M in cash; the Flames are putting up $40M.

MAYOR GONDEK: This is a generational investment in place making, creating space for community to gather. This entertainment hub will feature a new event centre and a community arena, along with critical infrastructure required to support growth and development.

KLASZUS: That was Mayor Jyoti Gondek speaking at a press conference on April 25, 2023, the day the new deal was approved and announced.

In this episode, we’re going to dig into how city hall went from a $290 million commitment in 2019 to committing over $800 million in cash to build a new arena. We’ll look at why this deal is far less transparent than the last one. And we’re going to hear from council members, including the ones I just quoted, about why they voted “yes”—even when they campaigned on doing the opposite.

I think they railroaded council and will take us for all we’re worth.

How Calgary's arena history is repeating itself

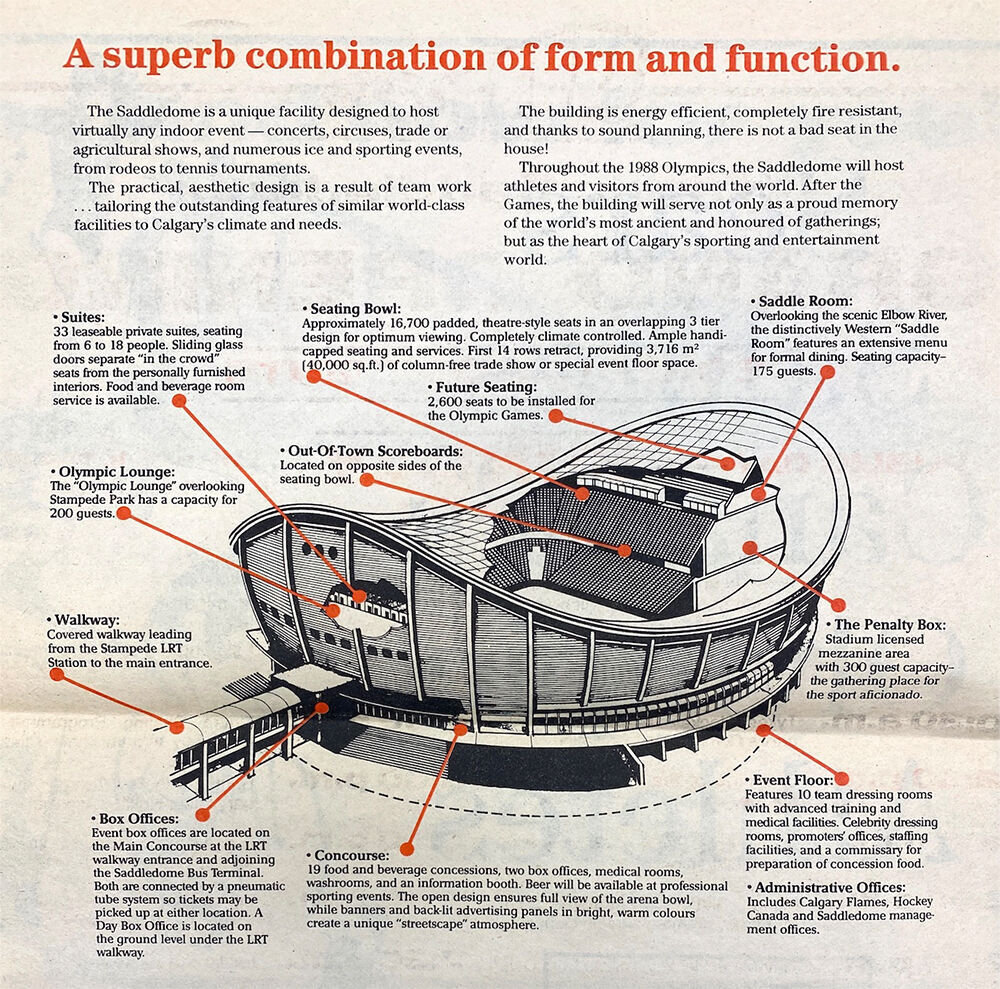

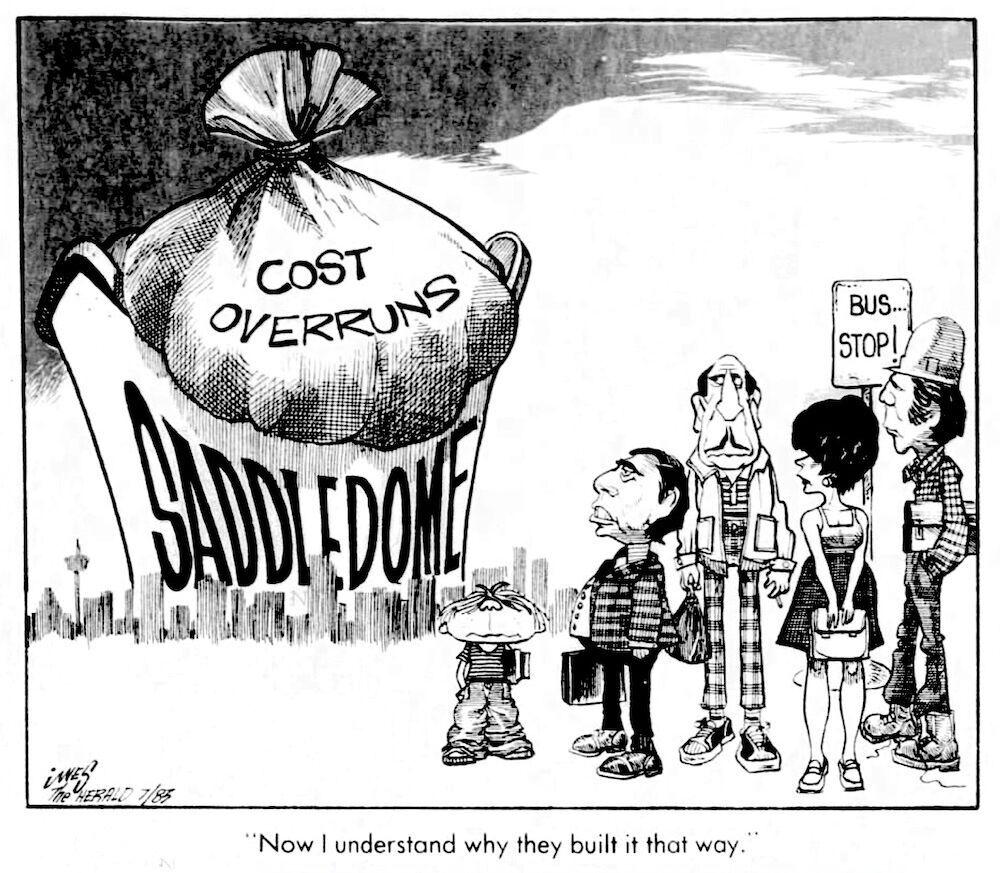

KLASZUS: Let’s go back a few years. It’s been nearly a decade since the Flames first put forward a proposal to replace the aging Saddledome. When the Dome opened in 1983, it was an architectural marvel that was fully funded by public dollars. The municipal, provincial and federal governments shared the cost—a move that was contentious at the time. Here’s a CBC-TV story from 1983.

PETER MANSBRIDGE (CBC): Thousands of Calgarians got a glimpse of the Saddledome this weekend. It’s their first major Olympic installation, completed more than four years ahead of the games.

BOB NICHOLSON (CBC): At three acres of precast concrete, it’s the largest free-span concrete roof in the world, and very expensive to build.

KLASZUS: Over 30 years later, in 2015, the Flames proposed a new pro sports megaproject called CalgaryNEXT to replace both the Saddledome and McMahon Stadium. The idea was that it would be an NHL rink combined with an indoor fieldhouse that could also be used for CFL games. Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation, or CSEC, owns both the Flames and the Stampeders. And CalgaryNEXT would bring these teams into one house, so to speak.

At the time, CSEC said this wasn’t just about the sports facilities. It was also pitched as a way to invigorate civic pride and revitalize a long-neglected part of the city core.

CalgaryNEXT PROMO VIDEO: Now is the right time to reimagine the land along Calgary’s Bow River. CalgaryNEXT can be the catalyst that creates a unique new neighbourhood called West Village. Imagine a new sense of place in Calgary’s urban landscape, with an active community featuring an arcade lined with shops and cafés. It will connect the Sunalta LRT station to the river and provide a comfortable place to gather in any season.

KLASZUS: The proposal was for the west side of downtown, where you have the old Greyhound building and car dealerships.

KLASZUS: Here’s former CSEC president and CEO Ken King in 2016.

KING: Used to be you’d build a stadium some place, you’d build an arena some place, and that would be fine—and you’d live happily ever after. What’s happening now, and if you look at this thing in Edmonton or in Detroit, they’re phenomenally changing those cities. These are powerful.

KLASZUS: But the CalgaryNEXT proposal never really lifted off. For one thing, the land is contaminated with creosote and cleanup would be expensive. And then in early 2016, NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman got involved.

BETTMAN: I believe that if this project is going to happen, the mayor needs to embrace it; the city needs to embrace it. And if he’s not prepared to embrace it, then people will have to deal with that.

KLASZUS: Naheed Nenshi was the mayor of Calgary at the time, and he fought back.

NENSHI: Perhaps in other cities that he has come to, the city councils have just written cheques based on back of a napkin proposals, without any consultation to the public, or without any analysis. That’s not how we operate here.

Nenshi cast himself as standing up to wealthy elites who would fleece the city and its citizens for a new arena.

KLASZUS: When CalgaryNEXT was rolled out, the early call was for the city to contribute $200 million to a project estimated to cost just under $900 million. But in 2016, city admin pegged the actual project cost for CalgaryNEXT at more like $1.8 billion, which effectively killed any momentum that CalgaryNEXT had.

The following year, in 2017, Nenshi ran for re-election against a conservative candidate named Bill Smith. But he also sparred publicly with the Flames, with Nenshi casting himself as standing up to wealthy elites who would fleece the city and its citizens for a new arena.

Over time, Nenshi’s position softened. Jeff Davison, who was a city councillor at the time, spearheaded the push for an arena deal. And in July 2019, city hall announced that a deal had been reached between the city, CSEC and the Stampede. But now council had to decide. The new arena would cost $550 million—and be split 50/50 between the Flames and the city. And we were told this would be a crucial part of the Rivers District, which is the city’s plan for a culture and entertainment district in Victoria Park.

NENSHI: I think ultimately this deal meets my criterion of public good for public benefit.

KLASZUS: The 2019 deal was especially controversial because council had just cut $60 million in city services like transit to ease the tax burden on small businesses. City hall invited citizen feedback on that arena deal, as council was set to vote on it a week after it had been announced. And even then, critics called it a rush job. Here’s what former councillor Evan Woolley said at the time.

WOOLLEY: There is no reason to have rushed the deal. I find it to be a bullying tactic, and an unnecessary ultimatum. I don’t understand what council is so afraid of—and so unwilling to face the public in even a semblance of a conversation and the most basic of communications. I am for building an arena. I’m a lifelong Flames fan. Being critical about one week of engagement doesn’t make me anti-Flames. It doesn’t mean I’m trying to kill this deal. It means I’m trying to do my job.

KLASZUS: It got pretty lively on the floor of council that summer. At one point Woolley moved to delay the arena vote. Here was Councillor Davison’s rejoinder.

DAVISON: You should know that if this passes, this deal is done tonight, and you will forever be known as the council that likely lost the Calgary Flames.

KLASZUS: Woolley’s motion did not pass. And on July 30, the day of the big vote, city administration laid out its case for the deal in public.

I don’t understand what council is so afraid of — and so unwilling to face the public in even a semblance of a conversation.

GLENDA COLE: You have the opportunity today to approve a deal and a series of transactions that we believe will accelerate the redevelopment of east Victoria Park in a manner similar to that of East Village—and will benefit all Calgarians.

KLASZUS: That was Glenda Cole, the acting city manager at the time. At that meeting, council members asked questions about details like the Flames getting options to purchase prime city land in Victoria Park as part of the deal. (Similar land options for the Flames are also part of the 2023 deal.)

WOOLLEY: Handing Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation the opportunity for hundreds of millions of dollars in development rights in the absence of free and open competition is totally unacceptable.

KLASZUS: Council ultimately voted 11-4 in favour of that deal. The new arena looked good to go. But of course—it didn’t work out that way. For one thing, costs went up, as they inevitably do. This happened with the Saddledome too in the early ‘80s.

BOB NICHOLSON (CBC): The Saddledome was originally supposed to cost $84 million dollars. But back in April, Olympic officials discovered the bill would be higher—as much as $16 million dollars higher.

KLASZUS: The budget for the new arena was already ballooning from $550 million to over $600 million. Council approved the revised budget in July 2021. This is sometimes referred to as “the 2021 deal.”

KLASZUS: But then, at the end of that year, there was a breakdown. One of the sticking points was the cost of sidewalks and solar panels, and who should pay for them. Those costs were relatively tiny but in any case, the Flames walked away. Gondek and Flames co-owner Murray Edwards had a meeting on December 21, 2021, and that was it. The deal was officially dead.

But—not for long! A few weeks later, in the first city council meeting of 2022, council agreed to a fresh start, creating a new arena committee. Here’s Councillor Sonya Sharp, who would become the committee’s chair, along with Councillors Peter Demong and Andre Chabot.

COUNCILLOR SHARP: It’s a new council and it’s a new year.

COUNCILLOR PETER DEMONG: Like everyone else, I wish we were not here talking about this today. But I also choose to see the positive. The world is a different place than it was when we made the deal in 2019… In a strange way, we’ve been given a gift—gift of time to rethink, to reassess.

COUNCILLOR CHABOT: I do think this is a better way forward than what was originally envisioned. It does continue to support the master plan for the entertainment district.

COUNCILLOR SHARP: And I really hope that you will consider this as the best decision for Calgary, and giving the opportunity to re-enter the partnership and talks with Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation.

This time, council debated deal behind closed doors

KLASZUS: You heard a little of what was said at council before the 2019 deal was passed. I’d like to share some of the 2023 council debate with you. But it doesn’t exist, because this time the conversations were kept entirely behind closed doors. This time, it took less than two minutes for council to approve the deal. We’ll hear that shortly.

The arena committee was made up of three councillors, plus two other prominent individuals: Brad Parry, the president and CEO of the city’s economic development agency; and Deborah Yedlin, president and CEO of the Calgary Chamber of Commerce.

YEDLIN: From an economic standpoint, my economic lens is this is all about the economic future of Calgary, and how we continue to grow as a city. This is a sign that we’re investing for the future, we have a vision for the future. We’re not afraid to invest in the future.

KLASZUS: That was Yedlin speaking at a committee meeting in October of 2022. Her comments were brief but marked one of the only times anyone said anything on that committee that wasn’t in closed session. Most of their meetings were in camera—which means the cameras were switched off. Councillor Courtney Walcott also spoke up at that October 2022 meeting, framing a new arena deal as a cultural investment.

COUNCILLOR WALCOTT: The future of our city, it’s changing because of how many people are being invited in. We’re inviting so many more people from around the world to be a part of this culture, and as we do so, in all honesty, we have to ask ourselves—do we actually have what we need to grow that culture here? And that’s how we need to look at our city’s infrastructure. That’s what the event centre could be. It could be a significant cornerstone to our city’s infrastructure that creates open and inclusive spaces for Calgarians from all stripes.

Work on this has been moving at the speed of business, not the speed of government. And that was one thing that we have all committed to.

KLASZUS: Now we’re going to listen to how the deal passed at council on April 25, 2023. Since it’s so short, I’m going to play the whole thing for you.

MAYOR GONDEK: Let’s go to the next item, which is 12.2.3. This is being moved by Councillor Sharp, seconded by Councillor Chabot. Go ahead, Councillor Sharp.

COUNCILLOR SHARP: Thank you Mayor. So, everyone always knows I’d like to take this opportunity to always thank council and thank administration when I’m standing up here. It’s one of these opportunities I like to do all the time. Thank you to the team, administration and all the externals, that have been working on this tirelessly. And what I also want to say is—stealing some words here from folks we’ve been using all week—work on this has been moving at the speed of business, not the speed of government. And that was one thing that we have all committed to when we’re being business friendly. So thank you. With that, as this [is a] confidential motion, there isn’t much I could say. I’m closed.

MAYOR GONDEK: Thank you very much. I will go to the vote now, if you could go to e-Scribe to vote everyone.

CITY CLERK: Mayor, all the votes are in.

MAYOR GONDEK: Please display the results. And that is carried unanimously.

The difference between the 2019 and 2023 deals

KLASZUS: This was followed, hours later, by a press conference in Victoria Park where Gondek, Sharp and Calgary Flames CEO John Bean announced the $1.2 billion deal alongside Premier Danielle Smith—who had just kicked off an election campaign.

The province wasn’t part of the last deal. But now they were kicking in $300 million to pay for infrastructure upgrades around the arena, including an underpass that will go under the CP train tracks on 6 Street S.E., connecting Victoria Park and East Village. A $53 million "community rink" is also included in the project and the province committed to covering half its cost.

PREMIER DANIELLE SMITH: On May 29th, I’m hoping Calgarians give our UCP government a clear mandate to proceed with this arena deal. Calgary, it’s time to move on with this project. We can’t afford to go back.

MAYOR GONDEK: And to my council colleagues, thank you for taking your commitment to public service to heart. Today marks 18 months since we were sworn in, and look at what we have accomplished together. I asked a lot from you in 2022 when I asked you to support a new chance at getting this project done. And again when I asked you to allow this process to take the time needed to build trust with our partners. We had a wide range of views on this project, and through civil discourse we arrived not only at a clear decision, but a unanimous decision.

PREMIER SMITH: Quite an achievement to have this be a unanimous decision of council. Those don’t happen often, so I think that shows an incredible amount of support for this deal.

Through civil discourse we arrived not only at a clear decision, but a unanimous decision.

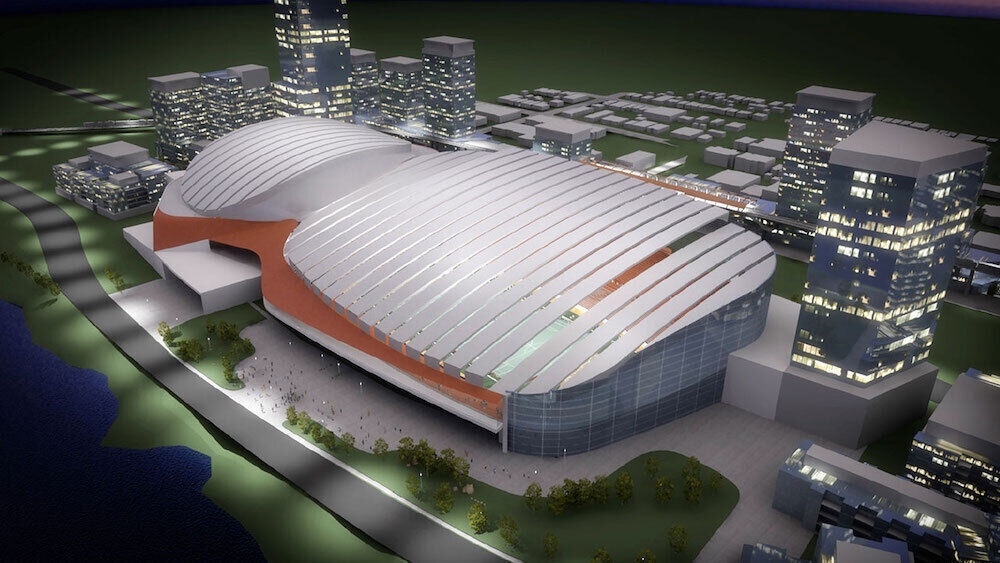

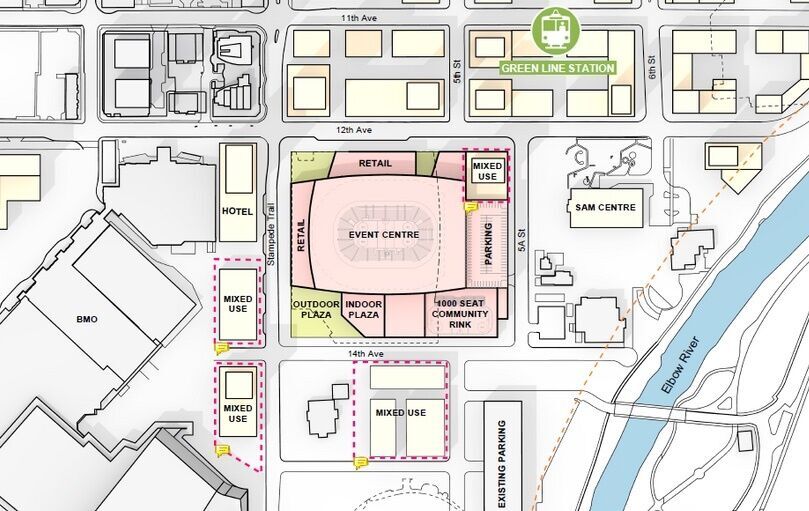

KLASZUS: The scope of the new deal is quite a bit bigger than the old agreement. The new project is 10 acres instead of seven, and the arena block alone is estimated to cost $926 million—which includes the arena itself, the additional community rink, a $35 million parkade and $38 million for indoor and outdoor community plazas. And then there are the infrastructure upgrades around the arena block, which push the total project cost to $1.2 billion.

MAYOR GONDEK: This time, we have laid out everything that needs to be done to ensure that this is a community-building process, and that the project itself is bigger than one facility. So the event centre and the community arena are one component of building out this district. The infrastructure that previously wasn’t talked about is now on display.

We know we need a 6th Street underpass. We know we need roadway improvements. We know there are many things that we need to do to bring this area to life. And that is transparent to every partner that is here. We all understand what the obligations are to deliver on a community capacity-building project.

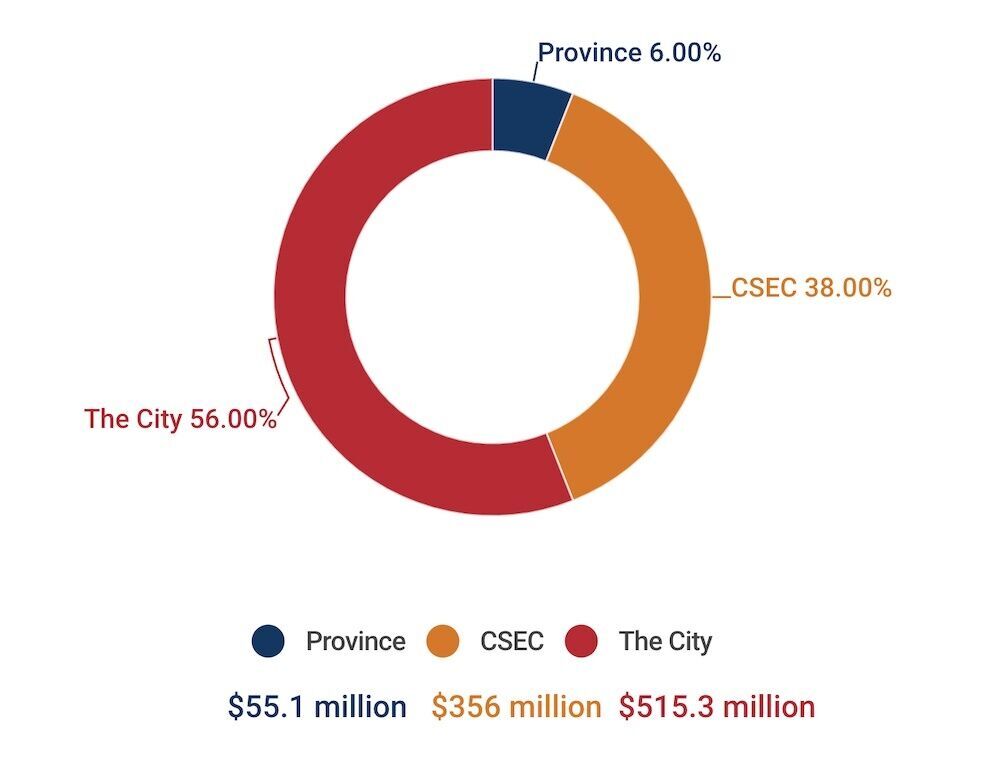

KLASZUS: When the city presents the arena deal, city hall’s contribution to the arena block is portrayed as $515 million. And that’s how it’s often been reported in the news too.

But the reality is that the city is putting up $853 million in cash, effectively acting as banker to the Flames by loaning them money for the Flames’ portion of the deal. And the city won’t recoup all of that until around the year 2060. Remember, the Flames are only putting in $40 million up front. And then they're making annual payments starting at $17 million. (The city and Flames have also agreed to split cost overruns 50/50.)

Here’s Michael Thompson, the city’s infrastructure general manager, speaking to the arena committee in June.

THOMPSON: The present value of the city’s commitment will be $515.3 million dollars funded from our reserves. In addition, the city will use our working capital to make available a long-term lease to Calgary Sports and Entertainment with a present value of $316 million dollars, which Calgary Sports and Entertainment will pay back to the city over 35 years.

I think we’ve gotten ourselves a pretty comfortable and conservative budget for this project.

KLASZUS: There are questions, to say the least, about how the city is going to pay for this. Some of the city portion of $515 million had already been earmarked from the previous deal and will be coming from reserves. But what about the $316 million loan to the Flames? Where specifically will those dollars come from? I asked the city and got this statement back: “We will be using the city’s cash reserves and liquid investments to fund the $316 million investment in the event centre.”

I was hoping for something a little more precise, but there you go.

The city announced on October 5 that final agreements had been signed. And in a Flames Q&A a couple days later, team president and CEO John Bean said the new deal is reason for optimism. And he spoke specifically about the $926 million for the arena block.

BEAN: We have a budget of $926. Last time, we started with a budget of $550; it grew to $600. You saw us do our dance. And you’re like, why did you ever do that? We did it for reasons. And we didn’t have a building design, so we started with a number that we kind of threw up on the wall.

Well, the good news is, this time we actually had a pretty good design of a building that was going to have 18,000 to 18,400 seats. So we had a pretty good idea of what we were looking for, so then we could cost it. And they updated the costing to 2021, when we were in the middle of the discussions in 2022. And so we knew that we were now starting with a number called $926…. So I think it’s all lined up well.

Last time, we started with a budget of $550; it grew to $600. You saw us do our dance.

KLASZUS: It’s interesting to me that both the city and the Flames now portray the previous deal as lacking, with inaccurate numbers that were pulled out of the air. This, of course, is a complete 180 from what they said at the time. We heard it was hugely beneficial for all Calgarians, that it was about more than just an arena—it was about the whole district. And we also heard that the deal was extremely rigorous. Here’s what former Councillor Davison, the champion of the last deal, said at the time.

DAVISON: We’ve done significant and almost unprecedented due diligence on this project.

KLASZUS: In any case, Councillor Sharp has called the current budget “comfortable and conservative” —and she told me there are good reasons the price tag is so much higher than last time.

COUNCILLOR SHARP: $300 million was missing from the last deal, just for infrastructure. This one has a community rink, so it was added cost there. Obviously, inflation… So if you go back to the last deal, you look at the price tag, add $300 million dollars to it. Probably a lot closer to the deal you see today, but that $300 million would have been a city cost, which was not included in the 2021 final deal.

No added taxes to taxpayers — that’s the question, there’s the answer.

'Definitely not a free lunch': How this affects city finances

KLASZUS: City hall has assured Calgarians that the new arena deal won’t cause “an increase in municipal taxes or new debt.” But it’s not that simple. I asked University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe about this.

TOMBE: I think that’s a very mechanical way to think about public finances. It makes it sound as though it’s a free lunch, which is definitely not the case. We’re using public funds that exist in order to provide support for this particular initiative. And it absolutely can be thought of as something that has implications for property taxes, or for the amount of support given to other activities that the city undertakes, because those funds could have been used for achieving other objectives.

If one prefers lower property taxes, these funds could have been used to facilitate that. Several hundred million dollars in public funds itself comes with, if you will, an opportunity cost. We could have used those funds to, say, lower debt service costs of the city, or invest it to earn a return. And then that flow that comes from that would then be used to support lower property taxes.

Those funds could have been used for achieving other objectives.

TOMBE: So foregoing an opportunity to have lowered property taxes does mean that this decision has implications for property taxes. And also, we’ve seen in Calgary over the past several years some really difficult decisions taken in terms of spending in different areas. The last time we had a deal around the arena, it was happening at the same time as the city was cutting back on many, in some cases, critical public services—including the amount of support given to first responders in different ways. And so there it was clear that the funds were also not just having implications for what property tax levels are, but you could think of it as having implications for how much we spend on other city services.

So it’s definitely not a free lunch. There are costs because we’re foregoing the opportunity to use those funds for other purposes. And recognizing that, I should emphasize, is not an argument for or against the arena. It’s just about ensuring that Calgarians have clear and transparent understanding of the choices that council is making. And this is a choice that comes with a cost.

KLASZUS: But here’s the thing: Do we have enough information to really understand the implications of the deal? Tombe says he doesn’t think so. The actual agreements still haven’t been made public. The city says they still need to be reviewed “for proprietary and financially sensitive details” and we’ll see them by the end of the year.

TOMBE: What are the risks that the city is exposed to in the future as a result of the deal? There are a lot of complexities that have just been completely pushed to the side in order to get a deal done. And I think in some quarters, having a deal regardless of the details is the objective, just so that we can say that a deal is done, and we’re moving forward. But the details do matter for the financial health of the city, for our ability to provide other public services, or for property taxes on businesses and individuals.

There are a lot of complexities that have just been completely pushed to the side in order to get a deal done.

TOMBE: So I think we should always have a broader public conversation when large decisions are being taken by council. And that means dispassionate, clear, accessible information being provided about the nature of the deal, and time to digest and explore what the implications of that deal is.

And we do this for so many other things. We probably do this more than we should in certain other things—thinking about changing a zoning bylaw restriction for a particular piece of property. [It] takes a very long time and inhibits building out the housing supply of the city, for example. But we don’t do that when we’re talking about hundreds of millions of dollars in support of an arena and the associated infrastructure and so on. So the conversation is definitely missing.

When council wants public input—and when it doesn't

KLASZUS: That’s an interesting point, and I asked Councillor Sharp about this. When the city was debating the housing strategy in September, one of the most contentious points was around changing the base level of zoning citywide to include rowhouses and townhouses. And in that debate, Sharp repeatedly advocated for the public to have a voice when it comes to zoning changes on individual parcels of land in their neighbourhoods.

COUNCILLOR SHARP: We can’t cut the public out of a process. A public hearing ensures the community voice is heard.

A lot of the community input was taken into consideration. And that actually helped shape negotiations.

KLASZUS: But on the arena deal, Sharp made no such call for public engagement. I asked her why she advocated so strongly for public input when someone wants to build a rowhouse down the street, but not when city hall wants to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on an NHL arena.

SHARP: I would say you’re actually comparing apples and oranges. And the reason I say that is because one of the biggest personal investments to people is their house. And what happens in their community is actually very important to them. And with [the arena], we’re not taking away public engagement. There was public engagement. With the housing strategy there is a clause in there to take away public engagement. So I would say that’s almost apples and oranges there.

But I would say, what we heard in 2019, actually all the way back to 2017—2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020, a lot of the community input was taken into consideration. And that actually helped shape negotiations for CAA ICON, who was doing the negotiation at this time.

Will there be an opportunity for the public to see this? Well, this file still has to go through a development permit. The public is going to see that. They’re going to submit comments. But for the negotiation piece, generally on infrastructure projects like this, there’s going to be a little less public involvement when this is the third time now that we need to get through this. And we know we need to fulfill an infrastructure project that Calgary has really had on the books since 2017.

I would say that we had a lot of feedback given in those years, and our negotiators had all of that information.

Why councillors changed their minds—and all voted 'yes'

KLASZUS: So a question I’ve heard people ask is: What really happened with that vote in April 2023? Why did council vote unanimously on a deal that sees the city forking over nearly three times what the last council agreed to in 2019 to build an arena? Why were there no critics?

Here’s former councillor and mayoral candidate Jeromy Farkas on the Calgary Eyeopener on CBC Radio in April 2023, after the announcement of the new deal.

FARKAS: There’re a number of different questions here, but just in terms of the political savvy that Danielle is showing by getting, of all people, Jyoti Gondek up on stage at what is essentially a UCP campaign event, smiling. She has essentially made this council complicit in this with a 15 to zero vote, making these progressive councillors like Councillor Walcott, Councillor Penner into the UCP sword and shield on these issues.

KLASZUS: I spoke directly with these and other councillors about why they voted the way they did.

COUNCILLOR KOURTNEY PENNER: I think for me, it’s really looking at who do we want to be as a city when we grow up, and what are the things that get us towards those goals? And I think for me, this is one of those milestone projects that gets us there. And so, is it favoured by everybody? No. If I was on the other side and being part of the Twitterati and I wasn’t on council, I’d probably be equally frustrated. I’m sure I would have been. Things are different on this side, when you look at the scope and the plans and the potential that arises from it. It’s hard not to get behind, actually.

KLASZUS: So part of the issue I think with this… if you compare it to 2019, with that deal, admin presented it to council, on the floor of council. It was presented in quite some detail. Dissected and debated on the floor of council. On this one, council passed it in literally 60 seconds. No debate, everything was done behind closed doors. So I hear you saying, how could you not when you look at it—but we haven’t looked at it. So how do you justify that it’s behind closed doors? And to paraphrase, it seems like you guys are essentially saying: trust us.

COUNCILLOR PENNER: There is, yeah. There is, absolutely. We are asking you to take a big box of trust, and ride the journey with us, for sure. I would say this. I don’t think we passed it in 60 seconds. It may seem like that, but that is the result of, I think, months of conversations and work and questions by previous skeptics, by current skeptics, and by people on all sides of the equation on the previous deal.

If I was on the other side and being part of the Twitterati and I wasn’t on council, I’d probably be equally frustrated.

COUNCILLOR PENNER: The deals, they’re not the same, and that’s a good thing, right? It’s a good thing that we didn’t rinse and repeat with just a bigger price tag. I think it’s a good thing that we went back and actually got services and amenities for Calgarians that they can use and that they can be proud of, and that can anchor a part of the city that needs a much-needed investment. Whether that is road right-of-way, whether that is coinciding with the Green Line that is coming through or the BMO—it’s really about tying those pieces together. This deal really tied those pieces together in ways that weren’t imagined before. So, for me, the public realm side of things was really critical and really important, and I think we got that.

So why wasn’t it put on the floor of council in ways that it was before? I think, in part, because that’s actually not how good deals happen. I mean, imagine if you did your real estate deal—for anyone to come and watch your back-and-forth negotiation on purchasing a house or buying a car, and it was sort of open to the public. I don’t think anyone would actually come with their best and most honest selves. I think they would always be guarded and afraid. And so this allowed for a degree more of honesty between the parties on what they were willing to give, but also what they were willing to give up.

For me, the public realm side of things was really critical and really important, and I think we got that.

COUNCILLOR EVAN SPENCER: Yeah, I would say obviously the conversation was insulated this time for political reasons, right, because it’s a super contentious decision point. But in the end, all those documents are going to be public. It’s just, we didn’t do a plebiscite. There wasn’t the runway for a long-term conversation ahead of time. And I think the fact that it was essentially a refresh of a previous conversation—Calgarians were heard.

KLASZUS: Spencer said that council members also heard a convincing case from CAA ICON, the consultant hired by city hall to advise the city and negotiate the deal.

COUNCILLOR SPENCER: They did a really good job of presenting the trade-offs of what would happen if—the window that was available to the city to refresh this infrastructure. And if we chose to kind of put our feet down and say, you know, we’re not spending public money, or not a large chunk of public money in this direction, where this conversation could potentially go.

And it certainly wasn’t—it wouldn’t have been a scare tactic. It was just, here’s pragmatically what we’ve seen happen in other jurisdictions. And then again, you add that to the long-term picture thinking, the fact that we have BMO coming online, and some of these other pieces—I think that’s why you got the unanimous vote. You start to connect all those dots, and you went, boy, do we really want to be the council that kind of divests of our arts and culture and entertainment district?

I would say obviously the conversation was insulated this time for political reasons.

KLASZUS: I also reached out to Councillor Jasmine Mian. Remember, as a candidate she’d said that “if there’s a market for a new Flames arena, the owners could build it themselves.” Mian is currently on maternity leave but she sent The Sprawl a statement. And in that statement she noted that the Saddledome was built with public money and has been an important feature of the city and its culture for decades.

“It’s a big part of the city’s image and I moved away from my staunch opposition because I started to see that it was public money that had led to this public benefit,” Mian wrote. “The more I learned about the vision for downtown and the state of disrepair of the Saddledome, the more I was convinced that a replacement was needed for the next 30 years and there likely had to be a role for the public in that, but there was also a role for CSEC, who would operate the facility in a way that the city just didn’t have the expertise or capacity to do.”

Like other council members, Mian says this deal is better than the last one. “I’m someone who was very critical of the project as an observer, and I’m also someone who changed my mind about it. Both perspectives can co-exist and both are important.”

I moved away from my staunch opposition because I started to see that it was public money that had led to this public benefit.

KLASZUS: I also asked Councillor Courtney Walcott what changed for him.

COUNCILLOR WALCOTT: The big change is really a question around what did we get for the money that citizens were putting into it. Being able to leverage the city's money to get more than that from our different partners: the province and CSEC. We put in $537 [million], we got back $680 million to support a project like this. That’s a big change from the first one in which we put a lot of money up. And in all honesty, we didn't actually get anything leveraged out of it outside of the arena itself.

KLASZUS: I read him his previous comments on how “Calgarians deserve the opportunity to weigh in on any further billionaire bailouts by their city council” and how “Calgarians know better than to believe that massive public subsidies to private billionaires will revitalize our economy.”

KLASZUS TO COUNCILLOR WALCOTT: So how do you square that with your position now?

COUNCILLOR WALCOTT: The big one there is really around whether or not I got my way entirely, and the answer will never be yes. When you’re looking at some of the decisions about how these processes go, I am subject to my colleagues and the way that we want to work out. So, on a balance of probabilities, it didn’t all go my way.

The big question though on revitalization was the idea of: What are we getting back? Will an arena itself just suddenly be the catalyst for everything? And the answer was never yes; it was always no. The city needed different things. Were we going to get land back? Were we going to be forced to build an underpass that was written into the old contract, but not priced out? The answer to that was yes.

There was nothing actually revitalizing about [the previous deal].

COUNCILLOR WALCOTT: Were we actually going to be sending land over to CSEC and the Stampede, and not through us at all? Do we retain any ownership of anything? And the answer to all those questions was no. We didn’t get any of that in the first deal. There was nothing actually revitalizing about it, nothing coming back to the city in these processes.

The new deal itself actually sees these assets returned to us, and sees these assets not only built, but paid for by other people and maintained by the city. We get to hold it. We get the land, we get the work on the underpass, and we don’t want to pay for it. We get the actual uplift in the area. We finish BMO; Stampede Trail is now ours. The list of things that we receive for the public is way different than the first time.

But I admit, it’s never the way we want because we sent a different priority list to the province. But when it comes down to our partners offering funding, sometimes you see what’s available out there and you make the deal accordingly.

KLASZUS: I also asked Walcott why this deal was so much less transparent than the 2019 one.

COUNCILLOR WALCOTT: The complexities of actually getting all these different partners here meant that there were a lot of different demands of privacy to actually ensure that the business deal was done correctly, versus what we saw get created on the floor. I would actually put the argument that some of the ways that the last process was done is what contributed to some of its biggest challenges and flaws, and not improvement. Because we didn’t look at it like an investment or a deal. We looked at it as something that we can negotiate our way through, without actually allowing people with expertise to do the negotiations on our behalf.

That was such a huge problem for me—is that councillors, we are not business experts, even though some of us will have that commentary in the public. This deal we actually wanted to put in the hands of people who knew every aspect of creating these deals; give them full control of doing it. And one aspect of doing that is making sure that you’re not building it on the floor of council, and that you’re actually allowing people to negotiate in good faith.

This deal we actually wanted to put in the hands of people who knew every aspect of creating these deals; give them full control of doing it.

KLASZUS: It's worth noting that the city hired a professional negotiator for the 2019 deal as well. And the city didn't build that deal on the floor of council; it was negotiated behind closed doors, admin presented it publicly, and then council debated and voted on it.

I asked Councillor Sharp about the lack of transparency on this deal, compared to the last one.

COUNCILLOR SHARP: What I will say about this time around—everything about this was going to be different. It was one of the first things that I said as the chair. What I’ve learned from business, and what I’ve learned from coming from the business world, is their agreement requires a high level of trust and honesty between partners. And negotiating in public is not an effective way to do that.

We hired a third party, CAA ICON, who did the negotiation for administration, and for the politicians—so for council. And I think that’s one of the main reasons why we saw this agreement succeed, and why we have a superior deal compared to last time.

KLASZUS: The company that advised and negotiated the deal for the city is called CAA ICON. And that same company is now the project’s development manager. It’s an American consulting firm that cities hire to get pro sports stadiums and arenas built. And I asked Sharp if it isn’t a conflict of interest for a negotiator to broker a deal that they are now the direct beneficiary of. She suggested I ask administration that question, as council members aren’t involved in procurement.

The U.S. company that advised and negotiated the deal for the city is now the project’s development manager.

KLASZUS: I did ask city admin, and the city sent back this statement: “To ensure fairness in the procurement process, the city required that the CAA ICON team developing and submitting the development manager proposal did not include any person from CAA ICON involved in the negotiation and advisory services work and CAA ICON’s proposal team members did not have access to confidential information about the Event Centre project.”

The last word: Top of the Dome

KLASZUS: Okay. I think at this point many of us are left with more questions than answers. We’ve heard a lot from politicians about what the Saddledome and the new arena mean for the culture of the city.

But speaking of culture… what I really want to know is… with the Dome slated for demolition yet again, has anyone checked on our local friend from the movie FUBAR?

TERRY CAHILL: My name is Terry Cahill, loyal fan to the Calgary Flames.

…So, up top there, top of the Dome, that’s where there’s like a different energy, you know, it’s a little bit more gritty.

…You can see the whole rink! These seats are sweet!

Top of the Dome to ya! Awooooooooooooo!

KLASZUS: Maaaaaybe that’s a future episode.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

UPDATE: The numbers in this story have been updated to reflect city hall's $853 million cash commitment to the arena project, as articulated in the City of Calgary's 2023 annual financial report. This is higher than the $831 million originally cited in this story.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!