Illustration: Sarah Slaughter

Game over: How Calgary killed its primary transit network

Will we try again — and get it right this time?

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!

COUNCILLOR RAJ DHALIWAL: If you look at all the world-class cities, transit is one of the backbones.

COUNCILLOR JASMINE MIAN: Fundamentally, if you prioritize a primary transit network, you won't have as much coverage. And so it will be harder to reach some of those nooks and crannies of the city.

MIKE MAHAR (ATU LOCAL 583): I'm actually worried for the system and worried for our members as to when they're going to catch up.

JEREMY KLASZUS (HOST): It was supposed to be the cornerstone of Calgary’s transit system: A primary transit network of high-frequency service. It would include LRT, BRT—that’s bus rapid transit—and other busy bus routes. And on this primary transit network, CTrains and buses would come every 10 minutes. This frequency would change how we get around Calgary. It would get many us out of our cars. It would incentivize more Calgarians to take transit instead of driving.

A decade ago, this plan was heralded by city hall as a new vision for a rapidly-growing city that had been largely built for the car. A city that was stuck on sprawl—and trying to change direction after the fact.

But today, the reality of that vision is nowhere to be seen. Calgarians are still stuck at the bus stop, waiting for a promise that has not arrived. We’ve actually moved backwards on key transit metrics over the years—and not just because of the pandemic either. Even before that, our previous city council made decisions that thwarted what little of the primary transit network we had. And the city’s newly-approved four-year budget for 2023 to 2026 won’t change that anytime soon, as we’ll hear in this episode.

The idea of better, more frequent transit is a key idea in numerous city plans over the past three decades. Growth plans, transportation plans, climate plans. City hall loves to crank out these plans and policies—dropping layers and layers of them. They overlap and click together—or don’t. It’s almost like a giant game of Tetris. And as the blocks pile ever higher and higher, it can start to get ugly.

So is it game over for Calgary’s primary transit network? Will transit in Calgary be left to languish, stretched ever thinner as the city continues to grow? Or will we try again—and get it right this time?

Calgarians are still stuck at the bus stop, waiting for a promise that has not arrived.

The beginnings of the primary transit network

Let’s go back just over a decade, to 2011.

LISA WOLANSKY (SHAW TV REPORTER): RouteAhead will combine past and current Calgary Transit research and look towards the future of our city's transit system over the next 30 years. Changes are in the works.

KLASZUS: At the time, Calgary was a city of about 1.1 million people. And city hall put together a road map for the future of transit in Calgary—and they called this plan RouteAhead.

CHRIS JORDAN (CITY OF CALGARY): How does Calgary Transit evolve? How do we serve our customers? And what will our long term capital plan be? What would we look like in increments? Ten years, 20 years, 30 years in the future.

KLASZUS: This plan came out of other city plans. There was the GoPlan of the mid-’90s. ImagineCALGARY a decade later. And most significantly, in 2009, city council approved something called Plan It Calgary. And Plan It Calgary was made up of two blueprints for the city’s future: the Municipal Development Plan and the Calgary Transportation Plan.

This is David Cooper, a former Calgary Transit planner who went on to planning roles in Vancouver and Toronto and now runs his own transit consultancy.

DAVID COOPER: When we had Plan It Calgary, the first integrated land use and transportation plan, the idea was to start shaping the city around transit. So being the light rail system or high frequency bus service to provide a level of certainty to developers, provide a level of certainty to the community that you can have almost a turn up and go type system.

One of the things that is very challenging here in Calgary… is you have decided to have a coverage-based service.

KLASZUS: This primary transit network would be a major shift from what Calgarians were used to. But before we go any further—what is a primary transit network, exactly?

FILIP MAJCHERKIEWICZ: Frequent and always there. So it's defined as having service on a corridor every 10 minutes for 15 hours a day, seven days a week.

KLASZUS: This is Filip Majcherkiewicz, who leads service planning at Calgary Transit.

MAJCHERKIEWICZ: Another way of visualizing it is when a bus route is coming once an hour, you tend to have to schedule your entire life around the bus route. You pick a certain doctor's appointment, because that's when the bus will be able to take you there.

When the bus route is coming every half an hour, you can start planning your life around the schedule of the bus route. So, you know, a 2 p.m. appointment, I have to be on the 123 bus, okay. But at 10 minutes, the schedule goes out the door. You just leave whenever you need to.

And when I was in grad school, I often found myself making that trade off. I had a local bus route that was a block away from me, came every half an hour, took me to where I needed—most of the places I used to go. But I often found myself walking a kilometre to the central hub, because I didn't need to worry about the schedule. I would just go there, stand for a couple minutes, bus would show up and off I go.

KLASZUS: Here’s how Sharon Fleming, the director of Calgary Transit, described it to city council during budget week in November.

SHARON FLEMING: The ability to arrive at a stop and not plan your trip with a schedule is what makes transit work for people. They can be spontaneous. They can make it more of a routine part of their day, rather than having to plan ahead. And the risk of missed connections goes down dramatically when you know that there is another bus coming within 10 minutes. So I think it just changes the game in terms of transit reliability, and the willingness for people to reduce the number of cars they have in their household—or not rely on a car at all.

KLASZUS: So that’s a primary transit network. And the Calgary Transportation Plan that council approved in 2009 put it at the centre of the city’s future: “The highest priority for transportation capital and operating investment should be the primary transit network and supporting infrastructure (including walking and cycling infrastructure).”

The risk of missed connections goes down dramatically when you know that there is another bus coming within 10 minutes.

KLASZUS: That’s what’s on paper. The primary transit network was to form “the foundation of the transit system.” And there were targets for population and jobs along the route. The idea was that, by 2070, almost half of all jobs in Calgary would be along the primary transit network—along with two-thirds of the city’s population.

Before 2011, none of Calgary Transit’s routes could be considered primary transit by the city’s definition—because they weren’t frequent enough. They weren’t coming every 10 minutes, seven days a week. But in 2011, the CTrain started operating at that level—and so did buses on Centre Street north.

So Calgary had part of a primary transit network. The beginnings of one. So far, so good.

A Calgary Transportation Plan monitoring report went to council in 2013. And it flagged the challenges that were ahead if this idea was going to work. Namely, we wouldn’t get a proper primary transit network without a “predictable increase” in transit service hours. And not just a mild increase, either. Those service hours would need to increase at a faster rate than the population.

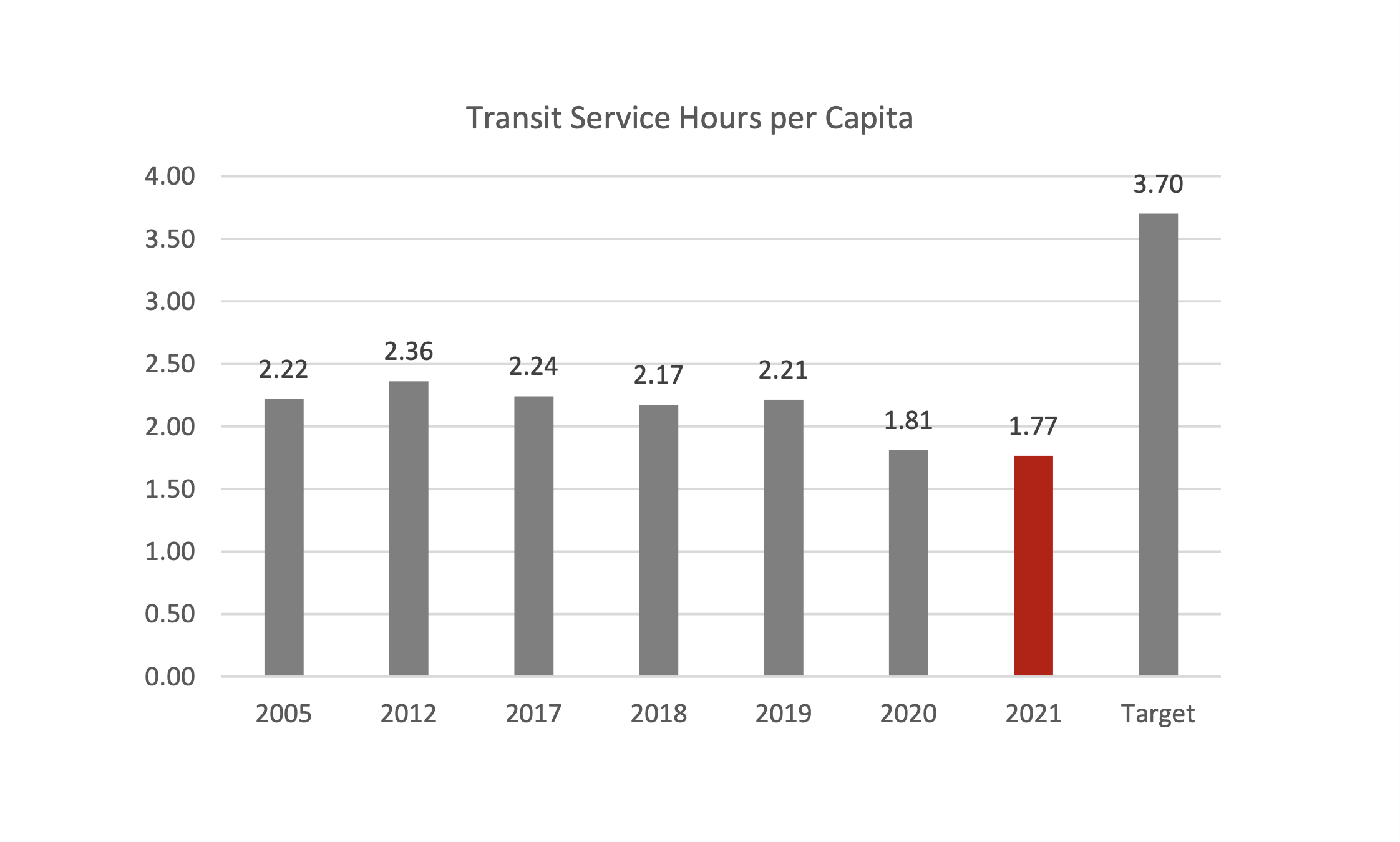

The Calgary Transportation Plan had set a long-range goal of 3.7 transit hours per capita, up from 2.4 in 2012. But by the summer of 2018, as the city struggled with the economic downturn and a resulting drop in transit ridership, there were troubling signs. The city wasn’t headed toward its transit goals at all—but away from them.

Here’s what former Mayor Naheed Nenshi said during a council meeting that summer, after looking at that year’s Calgary Transportation Plan monitoring report. That report noted that only 14% of Calgarians lived by the primary transit network.

NAHEED NENSHI: For many years, many of us, including me, have been talking about what I call the say-do gap: that we're very good at saying the right things in terms of what we're aiming towards, and we're not always good at making the daily decisions that actually get us there.

And if you read this report, well, you'll notice that there's a couple of very key areas where we're never going to get there on the current path. So we've set a goal, but we're never actually going to get there. That includes the 50-50 population split between developed and developing areas.

But for me, the most important one that I noticed is the transit goals. On the number of service hours per capita, we've actually been going down, and even though we are investing very significant amounts in transit, it's not going to get us to where we need to go.

KLASZUS: The number of transit service hours per capita in Calgary had been trending downward since 2012. And that has continued, exacerbated by the pandemic. Even so, Calgary was still running CTrains at a primary transit network frequency in 2018 when Nenshi voiced his concern.

But then came the summer of 2019.

We’re very good at saying the right things… and we’re not always good at making the daily decisions that actually get us there.

TARA SLONE, CTV NEWS: They demanded a break—and they got one. Calgary entrepreneurs will see a 10% cut in their property taxes from last year. This comes after an emergency debate at city hall in the face of what's being described as a tax revolt by small business owners.

CAROLYN KURY DE CASTILLO, GLOBAL NEWS: $71 million will come from reserve funds, while $60 million will be cut from the budget.

KLASZUS: That summer, city council decided to ease the spiking tax burden on small businesses by cutting elsewhere. Sixty million of cuts across city departments, including fire services, the city’s Indigenous Relations Office, and transit service hours.

TOMASIA DASILVA, GLOBAL NEWS: Speaking of delays, Calgarians will see those when it comes to public transit. More than 80,000 hours will be cut.

KLASZUS: When I asked Nenshi if he had any regrets from his time in office, the cuts from that summer were one of the things he mentioned. Those cuts were a “big mistake,” he said.

That decision finished off Calgary’s primary transit network. Prior to that, the CTrain came every ten minutes every day. So did buses on Centre Street north. But no longer.

And Nenshi gave a telling warning once those transit cuts came into effect in September of 2019.

MATTHEW CONRAD, GLOBAL NEWS: He says they don't want to make too many cuts, as he says if they do that, people could be afraid to use transit—and things could go into a death spiral.

KLASZUS: The primary transit network never recovered. In March of 2020, the pandemic hit. Ridership plummeted, and of course, so did fare revenue. The city laid off 450 transit workers, most of whom were drivers. And the primary transit network’s short-lived life was already over.

Life in a 'transit desert'

Calgarians elected a new city council a year ago, in 2021. And this council inherited the now-dormant primary transit network. But they also had additional complications to deal with. Low ridership. Low fare revenue. The opioid crisis. Safety concerns on transit.

And all the while, the city has continued to grow outward, straining the entire transit system further.

Raj Dhaliwal is one of the new councillors, and he represents Ward 5 in the city’s northeast. And he likens his ward to a transit desert.

COUNCILLOR RAJ DHALIWAL: Many of the residents there, they're newcomers, they're immigrants, international students, frontline workers, people who rely on transit. And what I'm finding out is that we don't have adequate service in Ward 5—what I call a transit desert. The people are there. They want to use transit, but they don't have transit.

So what I'm hearing day after day is: When is the service coming to Savanna? Route 59 is there but it's not servicing enough residents. Same thing in Cornerstone, CornerBrook... Many of these people, they don't have cars. Which is great because we want to be a less car-centric city, if you want to call it that. And they are looking for more service—but the service is not coming to them.

KLASZUS: Dhaliwal likens the Saddletowne CTrain station in his ward to an oasis in this transit desert.

DHALIWAL: The CTrain stops at Saddletowne. And after that, if you look at north of Saddletowne, that's where the community is growing, that's where Ward 5 is growing. Be it Savanna, be it Cityscape. Skyview is an older community, relatively, now. But Redstone, Cornerstone—these communities are growing really fast. Not just because of the organic population growth, but because of the migration from other parts of Canada.

They are looking for more service — but the service is not coming to them.

DHALIWAL: So when they look at what I want to call it a desert, there's an oasis. Like you said, Saddletowne is an oasis. But when they want to come to this oasis, they don't have enough transit to bring them to this oasis. Sometimes they're walking—someone told me that this person worked about a kilometre and a half, just to get to the bus service. So that's the biggest problem, that many of these people they rely on transit as their primary mode of transportation.

And if they don't have that, then they are either discouraged to go find employment, because there is not enough employment right there. And then, second is, some of them are, like I said, they are newer immigrants. It takes time for them to get the car license and all that. So it's such an interconnected paradigm where they just can't figure out how they can rely on transit to get them from point A to point B.

And that's where the discouragement comes in. Because they sometimes give up and they say, well, there is no transit. Transit is my primary mode of transportation—if there is no transit, how am I going to get from point A to B?

Making difficult transit trade offs

KLASZUS: Another first-term councillor says there needs to be more conversation about making difficult trade offs when it comes to Calgary’s transit system—because we’ve tried to have it all, and it’s not working.

Councillor Jasmine Mian represents Ward 3 in north-central Calgary. I spoke with Mian on the Route 124 Evanston bus that goes north of Stoney Trail in her ward.

KLASZUS: When you look at Calgary Transit and how the system is set up and how it's been set up over the last five or 10 years—what do you see as the strengths and weaknesses of that system, and what do you see as needing to change?

MIAN: The conversations we've had in the last year are that transit just can't be all things to all people. And when you talk about what kind of transit system you want, you want one with the most coverage and the most frequency—and is free, ideally. You can't have all of those things. Those are trade-offs that compete directly against each other.

And what we know from citizens is that the number one thing they want is frequency. They want to be able to show up and not have to worry about: did I just miss a bus that's not going to come for another half an hour or forty-five minutes, but that's going to be here within the next five to seven minutes.

But we can't do that all over the city. We can only do that, I think, on a primary transit network or spine. And I think that if we are able to do that, we would probably be able to provide something fundamentally different than what we do now.

The conversations we’ve had in the last year are that transit just can’t be all things to all people.

MIAN: We have a lot of coverage in the city. In the Municipal Development Plan, I think it's you have to be within 400 meters of a transit stop. That's actually really close. And I think what we're having is some conversations of: would people be willing to walk a little bit further, so like two minutes further, for a bus that comes every five minutes instead of every half an hour?

I think that those are the types of conversations we need to have, but none of those changes are easy. If you have a bus station or bus stop right outside your house right now, and you're going to lose that feeder route in order to prioritize something that's ultimately maybe better in the long term—that's a hard decision for those residents to accept.

KLASZUS: So what is the trade off? That primary transit network you talk about, having that spine with frequent service. Theoretically under that scenario, you have good transit in those places. What is the trade off there?

MIAN: So I think the trade off would mean fewer feeder routes into neighbourhoods. It would serve the city equitably, in terms of the fact that it would go into the each quadrant of the city the same. But it would mean that there are some gaps in other parts of the city. And I think the other benefit of it, I guess, is that you have an opportunity for better alignment with some of your planning goals—your transit oriented development, making density decisions.

Fundamentally, if you prioritize a primary transit network, you won’t have as much coverage.

MIAN: One of the complaints that we will hear, that I think is justified from citizens in public hearings, is you're making a decision to allow density here on the basis—or partially on the basis—that there's transit nearby. But that bus only comes once an hour. It's a fundamentally different conversation if that bus comes every five minutes.

KLASZUS: And so what about the equity side of it. Because—well, let's back up. What do you think of as being that primary transit network? Am I right of thinking of it as the CTrain line, Centre Street, the Number 3, all that stuff?

MIAN: The transit department's in in the process of sort of contemplating exactly what that spine would look like, but it would include all of those things. And it would be equitable so far as like it's not going to benefit part of the city more than another. But it certainly benefits the folks who live along the line more. But that's already the case. It's already true.

KLASZUS: One aspect of that is that the CTrain line, along the CTrain line, lots of people are going downtown. It feeds into downtown. So that network in a way serves—not exclusively people going downtown, but a lot of people going down downtown. Versus if you are a shift worker or you are traveling at off-peak times and not going downtown. Where you have to kind of do these awkward cross-town trips. I know that's something that's very challenging for a lot of people.

MIAN: Yeah, I agree with that. And I think that a primary transit network probably could serve some elements of that if we understood the patterns well—and that will be some of the decisions I think that have to be made at that time. But fundamentally, if you prioritize a primary transit network, you won't have as much coverage. So it will be harder to reach some of those nooks and crannies of the city on that type of system.

KLASZUS: And then what happens to those nooks and crannies? I know Calgary's experimented with transit on demand and different things like that.

MIAN: Yeah, I mean this will fundamentally come down to what we think about with the Municipal Development Plan and what we're willing to live with—and how far away from a transit stop everyone has to be. Those are all to be contemplated. I'm not exactly sure, but I mean just by principles alone, I think it would mean that there are places that are less served by transit than they are now.

Sprawl disproportionately affects women. As primary caregivers and shoppers, women in the suburbs are isolated.

MIAN: I guess the argument would be if they're already only coming once an hour, is that better or worse than it not coming and you have to walk a little bit further, but that comes every five minutes. That's the type of values based decision we're making. I think that we should move more towards that direction just because of the rapid growth of the city has had and the fact that I just think we should try and do some things really well than do everything at a not particularly great level. But that's not an easy conversation to have.

And I'm sure once faced with—if a route were to get taken away from my residents and they're talking to me directly about hey, I use this route to go to school, I use this route to get to my job, that's not going to be an easy trade off when you personalize that decision at all. It sounds good in theory—but in reality it's very painful.

KLASZUS: And what about the revenue side of it? The way it's set up now, the system is very heavily reliant on fare revenue—and to an extent, designed around that. How do you see that, and how do you see that changing?

MIAN: So it's been the case that transit is a 50% cost recovery basis. And that makes it extremely hard. It's a chicken and egg problem. You want to have a better transit system, but you need the revenue to be able to support that. You can't get the revenue unless you improve the transit system. So moving away from that metric entirely—I think there's an appetite on council right now to just get away from that. I mean, it's something we don't hold most of our services to. We certainly don't do that with roads. And I'm not suggesting that we start having toll roads everywhere across the city. But I think if we had had that from the beginning, you could make comparisons of apples to apples between maybe transit and roadways. You just can't do that because they've never been prioritized the same way or funded the same way.

It’s something we don’t hold most of our services to. We certainly don’t do that with roads.

KLASZUS: Speaking of transit revenue. Calgary Transit’s ridership has now rebounded to just over 80% of pre-pandemic levels. But not all riders rebound equally.

That’s made clear in a new report on the effects of the pandemic on Calgary Transit’s fare revenue. The researchers found that while children’s fares and low-income passes rebounded to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2021, adult fares have been a lot slower to pick back up.

Adult fare revenue was already low before the pandemic, due to the economic downturn. The pandemic basically exacerbated a trend that was already there—an increasing reliance on children’s fares and low-income passes, and a decreasing reliance on adult fares. Wenshuang Yu is a PhD student at the University of Calgary and one of the report’s authors.

WENSHUANG YU: it confirms that a lot of people, a lot of adults regular users, they don't actually want to go to the office. Therefore they won't buy the monthly passes. Or even if they go to the office, it might not be full time. Therefore they just drive, which might be easier.

KLASZUS: But of course driving isn’t an option for everyone. And you can see this in the data—as riders who use the low-income transit pass returned to Calgary Transit in force.

YU: it's not surprising because for them, they have fewer options. They might not have a car, they might not be able to drive, therefore they have to take public transit. So the recovery rate is higher for them.

KLASZUS: Yu and the other report authors are calling on city council to re-evaluate the financial framework for transit, noting that other cities recover much less from fares. In Vancouver, for example, it’s about 33% from fares. But their report also notes that there are no simple answers to this predicament.

They might not have a car, they might not be able to drive. Therefore they have to take public transit.

What the new budget means for transit

KLASZUS: Okay, so that brings us to the present moment. Calgary city council just approved its new four year budget, and is going to revisit RouteAhead in the coming months. Will this breathe new life into the primary transit network? Transit came up again and again during the budget public hearing.

JONAS CORNELSON: I'm asking you to fund 10-minute frequency, at least 15 hours a day, across the city in the next four-year budget.

PIERANN MOON: In looking at Calgary Transit's capital budget, how you bring the primary transit network to the greatest number of people must be your number one criterion for investment.

VARVARA BELENKO: Sprawl disproportionately affects women. As primary caregivers and shoppers, women in the suburbs are isolated and face barriers to fully realizing their potential and contributing to the city's economy. They spend hours every day driving kids to schools and activities, doing part-time and unpaid work instead of enjoying fulfilling and financially independent lives in a well connected community... Women are missing affordable, low-maintenance multifamily housing served by rapid transit.

KLASZUS: City council decided to freeze fares transit at 2022 levels rather than hiking them. They’re also making transit free for children 12 and under, using some city surplus funds to do this. But what about the primary transit network? Here’s what Calgary Transit director Sharon Fleming told council during budget week. She emphasized that Calgary Transit is facing a driver shortage of more than 800 transit operators.

We won’t probably be able to really invest in significant increases in the primary transit network until at least two years out.

SHARON FLEMING: So we have a situation where we haven't really recruited very much in the last four years. We have high attrition due to retirements. And we're looking at ramping up our training capacity, so that we can push through the recruits that we need for next year—just to return to 100% service as of 2019.

After that, through this budget, we do have some additional investments that we're looking forward to take advantage of. We did get a lot of capital investment as part of this budget. So we're really looking forward to taking advantage of some of the reliability of our fleet that will enable us to provide better service levels. But we won't probably be able to really invest in significant increases in the primary transit network until at least two years out...

What we're planning to do is to use the RouteAhead strategy ideas that are coming to council, first in December and then in Q1 of 2023, to eventually roll out an implementation plan and then return to council either next year or at mid-cycle adjustments to really push forward that strategy, and bring it forward to council to make a decision.

KLASZUS: One of the narratives that was nudged forward during budget week was that this isn’t a budget issue—at least, not now, due to the driver shortage. Here’s Councillor Mian and Fleming.

MIAN: I just want to ask this question really clearly for the public, which is: if I were to just write you a cheque today, would that solve the problem that you're facing right now?

FLEMING: No. We would certainly be able to put a major push on recruitment. But it takes time to recruit operators, to train operators, and then there's the associated fleet that goes along with equipping those operators to provide the service. So there's a lot that goes into that every day. But, I mean, could we write a cheque in a few years? Absolutely.

I’m actually worried for the system and worried for our members as to when they’re going to catch up.

KLASZUS: I reached out to the transit union about this. Mike Mahar, president of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 583, said the driver shortage it a real issue right now—not only is Calgary Transit understaffed, but the drivers that are there are overextended.

MIKE MAHAR: They've been running on overtime, and often forced overtime. Running a crew that's been suffering through a pandemic for two and a half years, and the mental exhaustion and all those things that have that have taken hold because of the long-term work environment. It just exacerbates the problem...

It takes a long time to train up a transit operator. You can't just put out a posting and have somebody on the job two weeks later. There's a lengthly screening, there's all the vulnerable sector searches and all those things. So it takes months to just to screen through after they've put out a posting to hire. Then when they made their final selection, and they'll hire a dozen people, seven or eight of them will make it through the training. And so they've lost quite a few then. And then a number of them, after they've been on the job for a little while, find that it wasn't for them.

KLASZUS: This is an issue that goes beyond Calgary Transit, and beyond the city itself. There’s a province-wide shortage of school bus drivers right now. Mahar pointed out that the city’s decision to lay off hundreds of drivers at the start of the pandemic didn’t help.

MAHAR: And so when they started chasing the eight ball, that ball was halfway down the table. I'm actually worried for the system and worried for our members as to when they're going to catch up. Because right now, we're heading right back into flu season. And again that absenteeism is going to going to spike. It's so predictable. It does it every year. And by January, we'll have 200, 250 operators off on any given day because of the flu and those types of things.

If you want people to use buses, give them some bus service they can use.

How transit routes will change—and have already

KLASZUS: So what does all of this mean for you? The RouteAhead refresh will likely focus heavily on the primary transit network. And if that’s the direction that the transit system goes, you might experience better or worse service, depending on where you live. That’s already happened to a point, as the city builds up and focuses on its BRT network.

I can use my own situation as an example. I used to be able to take the route 19 bus from my house in Renfrew to the University of Calgary. One bus all the way there. But when the MAX Orange bus was introduced in 2018, my route now had me walking 15 minutes to the BRT bus stop on 16th Avenue. I asked Calgary Transit planner Fil Majcherkiewicz about this specific situation.

KLASZUS: BRT, it's a good thing. But now, if I want to go to the university, I'm taking a bus to the Lions Park LRT station or I'm walking 15 minutes to Orange MAX stop. So I'm curious about those kinds of exchanges.

MAJCHERKIEWICZ: Certainly, and I think maybe I can reach to some of our design network principles. Even starting with RouteAhead, where there is a direction that we should be moving more towards connective network versus a duplicative one. And also that our routes should be more direct. And that we're willing to trade off perhaps a little bit more walk distance for routes that are faster to get you to your destination. And I think you see both of those elements at play in this specific example.

Yes, you might have a slightly longer walk to get to MAX Orange than you would to, say, route 19. But MAX Orange takes you to your destination faster, for most people, than route 19 would.

KLASZUS: For the record, it’s not a slightly longer walk in my case. We’re talking about a 15 minute walk versus a five minute one. But anyways, the point is more changes like these are likely coming, and they’re not always easy. Councillor Peter Demong pointed this out earlier this year. Council was discussing the citywide growth strategy. And this includes two new BRT projects that are meant to connect industrial areas with residential areas in the southeast.

COUNCILLOR PETER DEMONG: I appreciate you're trying to create an efficient system, ostensibly to get people to work. But if you don't have the buses at the other end dropping them off at residences or picking them up in the morning... what use is there? I'm hard pressed to put $20 million of op costs into a new couple of BRT systems when Ward 14 just got their transit slashed. I can't say that I'm impressed.

You're expanding BRTs over in places that we don't even know they're going to be required or used. And you're basically thinning the peanut butter on everywhere else in residences. So if you want people to use buses, give them some bus service they can use.

A lot of cities have moved towards a 15-minute network, which is really a realistic opportunity.

KLASZUS: Basically, get ready to do more walking, unless you live right by LRT or BRT. Calgary Transit director Sharon Fleming also suggested this when I spoke with her. She worked for the city of Toronto until 2018.

FLEMING: One thing that I learned from my experience in Toronto is I was willing to walk for quite a while to get to a service I knew was regular and frequent. So I wouldn't have to worry—you didn't have to check a schedule. You could just walk and you knew a bus would be there within five to 10. Whereas once you need to start looking at a schedule, and there are very specific times, it does serve a purpose—but it doesn't give you the freedom to make different choices. Where you're going to go on the fly or transfer to locations perhaps that might otherwise be a little bit more inconvenient. But now you can do it because you know that there's a frequent, reliable service that you can transfer to as well.

KLASZUS: What about the accessibility side of that? If I think of myself, sure, I can walk 15 minutes up to the BRT. But thinking of people who have different disabilities, mobility issues—that's not an option. So then where do they fit into the picture?

FLEMING: Well, we have specialized transit services for people with mobility issues, right? So while we hope to be able to provide them with traditional service, if that's not an option for them, and they qualify for the specialized service—whether it be for the entire trip or for the link trip so they can do a partial trip just to get to the primary transit network—that that's an option as well.

KLASZUS: Fleming is referring to Calgary Transit Access, which you need to book at least one day in advance.

In any case, it looks like we’re not getting a primary transit network anytime soon. It remains a vision—as it was when city hall first introduced the idea, over a decade ago.

There is strong policy rationale to have a primary transit network. But if we’re not providing that, we need to find an incremental way to get there.

KLASZUS: So now what? Well, David Cooper, the former Calgary Transit planner, told council during budget week that there are things Calgary Transit can do in the meantime—specifically with off-peak, cross-town service like the BRT routes.

COOPER: A lot of cities have moved towards a 15-minute network, which is really a realistic opportunity and incremental way to get to primary transit network. Off-peak transit service is really heavily relied upon by transit-dependent Calgarians. So this includes women, seniors, youth, newcomers, low-wage workers and members of the BIPOC community. And the work I've done nationally, the research we've done, [shows] women take more trips in the off peak, they take more frequent trips, they trip chain, and also more localized trips...

One of the things that is very challenging here in Calgary, which is a policy decision that was made a long time ago, is you have decided to have a coverage-based service. We try to hit every nook and cranny of the city within 95% of residential units that have access to transit. And it's really hindered our ability. And GM Morgan has heard this analogy from previous staff of the peanut butter on toast, where you take so much peanut butter, you only can put it on so much toast. Where you may taste it in one part of the piece of toast but then it gets really thinned out on others. And the challenge here is that there is an ability to recalibrate service. It requires engagement, it requires a lot of work at the council table on this to really see how we can get the most transformative investments within the budget you have...

There is strong policy rationale to have a primary transit network. But if we're not providing that, we need to find an incremental way to get there to better serve the transit needs of Calgarians. And this could be implemented very quickly in 2023. The vehicles are there. It's off-peak service. There's no capital. Staffing is an issue. That's something you see across the corporation, across sectors, but this can be done quite easily. Thank you.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!