Postcard of Calgary, circa 1930. (Glenbow Archives, University of Calgary)

A city of trees: The story and struggle of Calgary’s urban forest

Doubling the canopy won’t be easy.

Sprawlcast is Calgary’s in-depth municipal podcast. Made in collaboration with CJSW 90.9 FM, it’s a show for curious Calgarians who want a deeper understanding of the city they call home.

If you value in-depth Calgary journalism, support The Sprawl so we can do more stories like this one!

KEVIN LEE: We’re in the northwest corner of the Great Plains, and it is a dry country.

DIANE DALKIN: Trees matter for so many reasons.

FRANÇOISE CARDOU: We tend to think of trees as a dime a dozen. There’s trees everywhere. But trees are hard to grow in cities.

JEREMY KLASZUS (HOST): So picture this. It’s a hot summer day in Calgary. And as you go for a walk in your neighbourhood, and the sun beats down on the pavement, you’re drawn to the shady side of the street.

You may or may not have this shady side of the street, depending on where in the city you live. It all depends on trees. Trees are part of city life that we enjoy all the time but often take for granted. Trees can entice us outside, into the world—but a lack of trees can keep us inside, away from the street and the heat.

We’ve got a tree reporter who’s been digging into this...

MEGHAN LETT: My name is Meghan Lett, and I’m an intern journalist with The Sprawl.

KLASZUS: Meghan is from Saskatoon and came to Calgary for journalism school at SAIT.

LETT: So last summer, when I went home for the summer, I had a job at a local landscaping place and it made me think about where plants and trees come from—really for the first time. I think I just always took their presence for granted before. And so, when I got back to SAIT in the fall, I looked at all the lovely trees lining Heritage Hall, and I thought: How did these get here? Who planted them? Who made the decision? What is the story behind these trees?

KLASZUS: Meghan decided to dig into it for a school assignment.

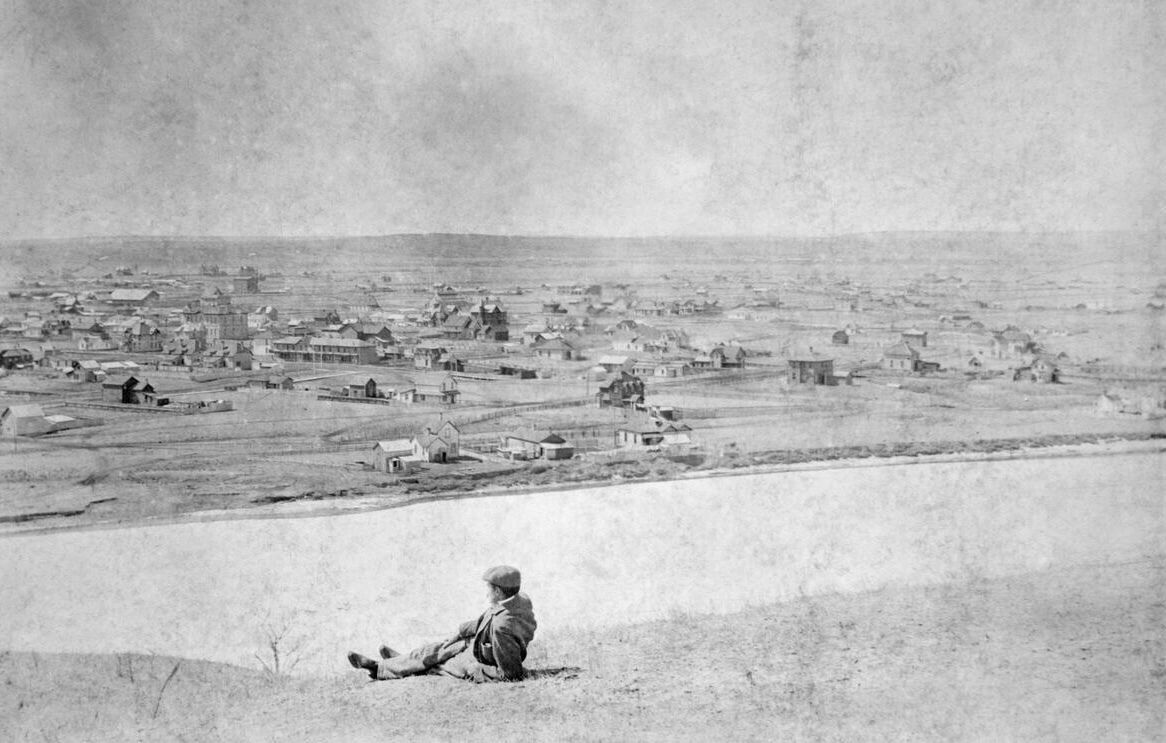

LETT: And I was surprised to discover that there were no trees at SAIT originally. I didn’t realize to the extent that Calgary was a majority treeless prairie land beforehand.

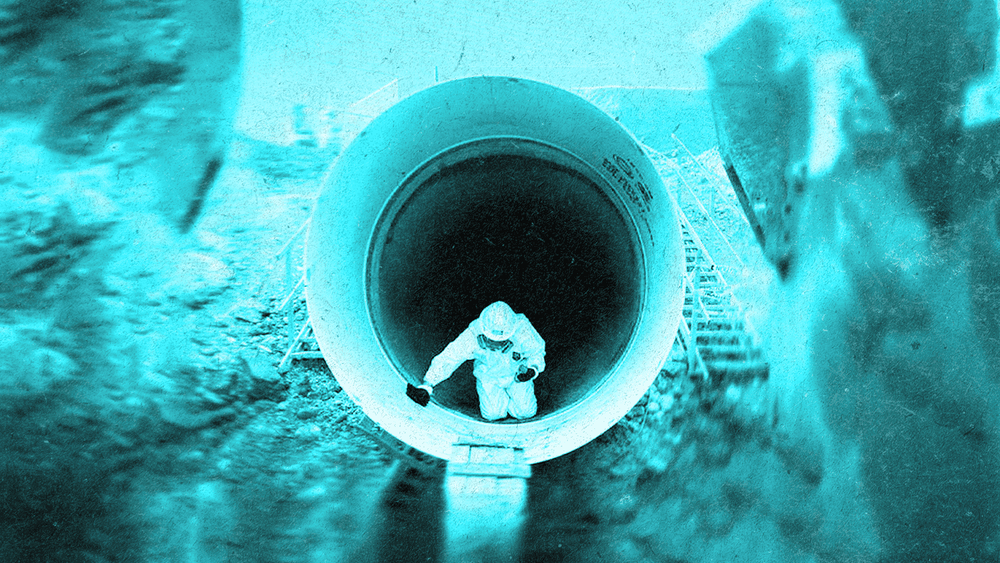

KLASZUS: When Fort Calgary was established 150 years ago in 1875, there weren’t many trees here. For the most part, the only trees were huddled around the river. Today, the city is home to about seven million trees. And although that might seem like a lot, it’s still not enough for a city of this size. Calgary’s urban canopy coverage is among the lowest in Canada, at 8.25%. By comparison, Toronto and Vancouver are around 30% percent.

City hall wants to double Calgary’s urban tree canopy to 16% by 2060. The city’s climate strategy sets an even more ambitious goal of doubling the canopy by 2050.

Growing the canopy sounds easy: just plant a bunch of trees. But it’s not so simple, as you might have noticed if you’ve seen newly-planted trees dying along a city street. At more than 1,000 meters above sea level, we’re the highest major city in Canada. It’s dry here. We’re working with arid prairie land. We’re also losing trees to urban redevelopment—and to natural threats like snowstorms and droughts and hotter summers.

Add it all up and it can seem amazing that we have any trees in Calgary at all. Let’s get into it.

Growing the canopy sounds easy: just plant a bunch of trees. But in Calgary, it’s not so simple.

‘A really tough tree place’: The beginnings of Calgary's urban forest

To understand the challenge of growing Calgary’s urban forest today, we need to go back to the 1800s, before Calgary was a town. Hal Eagletail of the Tsuut’ina Nation explained to me a few years ago how First Nations would travel to the Cypress Hills to harvest what they needed for tipis.

HAL EAGLETAIL: Everyone had title to Cypress because that was the only place on the prairie, at the time, that had an abundance of pine tree for our teepee and travois poles and for our travel. It was all prairie, right up to the mountains.

PAUL ATKINSON: One of the things we are certainly challenged with is originally this area wasn’t covered in trees.

KLASZUS: This is Paul Atkinson, the urban forestry lead for the City of Calgary.

ATKINSON: So when you look at some urban centres across the world, they were originally forests and the cities were cut into them. Here, we have the unique challenge of trees weren’t necessarily here in large quantity in the first place.

KLASZUS: To find out more about this challenge, Meghan Lett met up with veteran Calgary arborist Kevin Lee at Bowness Park.

LETT: Tell me about the prairie climate of Calgary and why it’s hard to grow trees here.

LEE: We’re in the northwest corner of the Great Plains, and it is a dry country. We’re in the rain shadows of the Canadian Rocky Mountain front in the Southern Alberta area, and it’s just a dry place.

The amazing thing about Calgary is we have four native trees in Calgary—four native trees!—and we can basically see almost all of them from right here.

KLASZUS: These four trees are the white spruce, the Rocky Mountain Douglas fir, the balsam poplar and the trembling aspen.

LEE: When you only have four native trees, that speaks very strongly that you’re in a really tough tree place.

When you look at some urban centres across the world, they were originally forests and the cities were cut into them.

KLASZUS: With trees on the prairies so scarce, settlers who arrived in Southern Alberta felt the lack of cover and planted trees for shelterbelts.

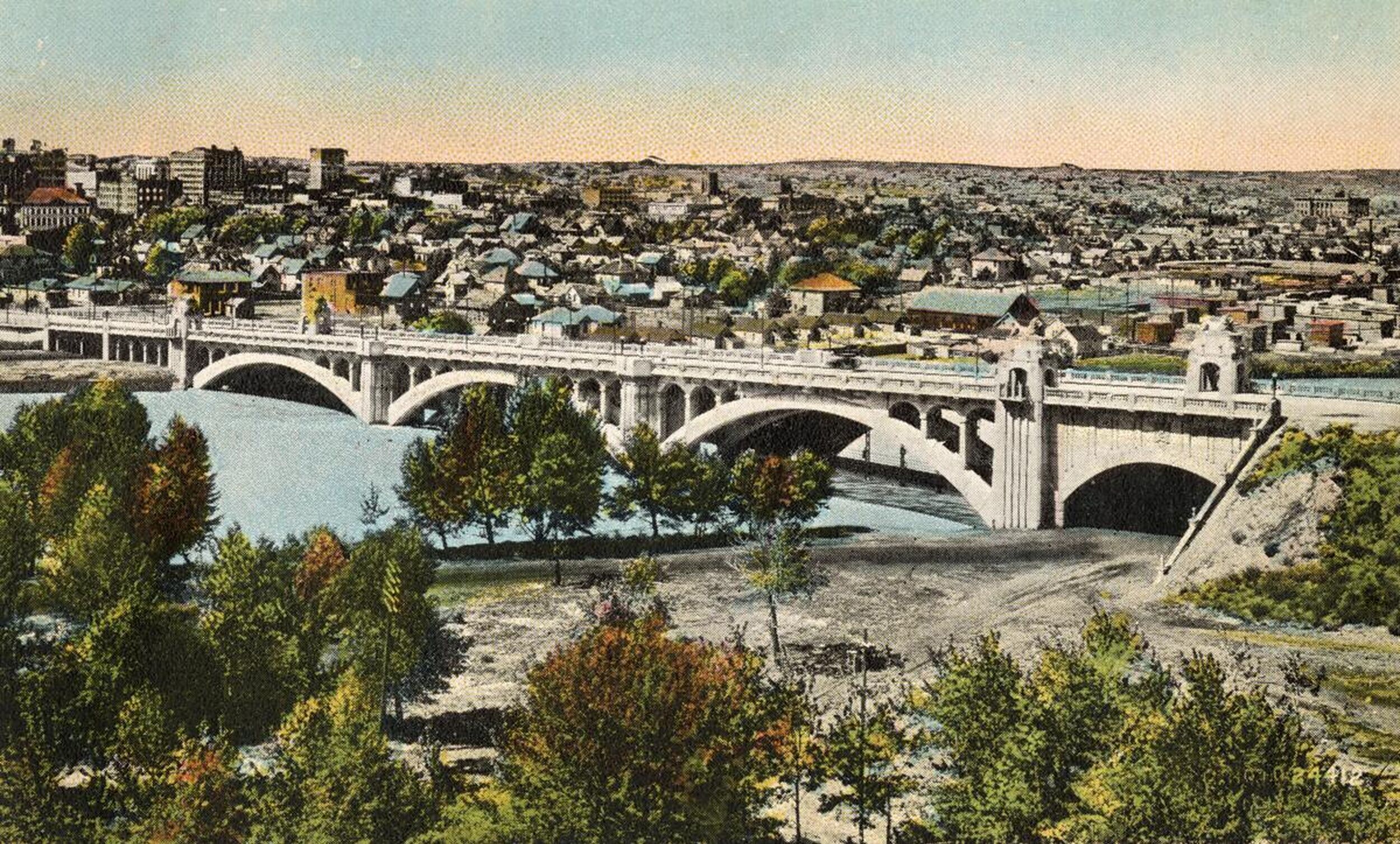

When the town of Calgary was incorporated in 1884, spruce trees were shipped by rail from the mountains and sold to residents for five cents each. That same year, William Pearce arrived from Ontario. He had a vision of Calgary as “a city of trees.”

DIANE DALKIN: William Pearce was the first one who recognized that this prairie province needed some trees.

KLASZUS: This is Diane Dalkin, president of the Friends of Reader Rock Garden Society.

DALKIN: He had an estate which is now near the bird sanctuary, where he planted hundreds of trees.

KLASZUS: William Pearce was a major figure in the colonization of the West. He was a surveyor for the Canadian government’s Department of the Interior and its senior officer in Western Canada. Pearce was passionate about prairie irrigation and he also wanted Calgary to have grand, tree-lined boulevards.

He used his position as a federal land agency inspector to set aside land for future Calgary parks. It’s largely because of Pearce that we have places like Prince’s Island Park and Memorial Drive along the Bow River.

Calgary launched a street tree planting program in 1895. This effort was later picked up by a different William: William Reader.

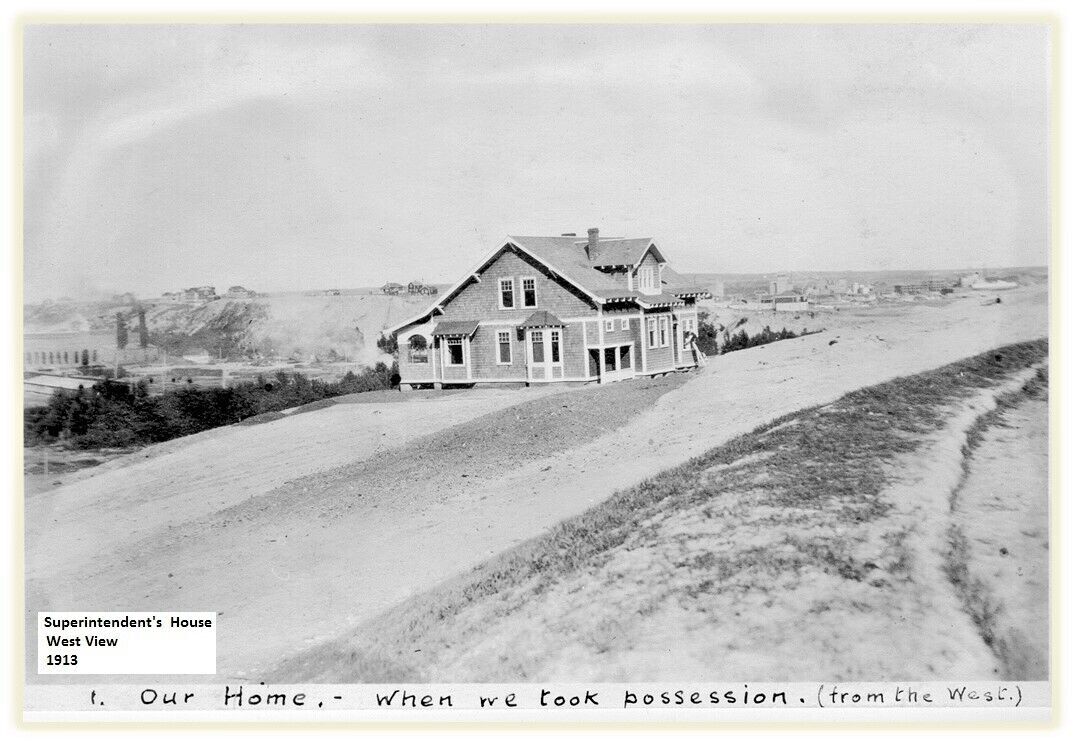

In the U.K., Reader had gone to school to become a teacher. But his true passion was horticulture. In 1908, he came to Canada to work as a gardener for cattle mogul Pat Burns, who was one of the Big Four ranchers who started the Calgary Stampede. Five years later, in 1913, Reader became the city’s third parks superintendent.

DALKIN: He was an amazing community builder. He was an environmentalist. And so he thought trees—even back then, he had a philosophy of the canopy being important here, needing shade and needing shelterbelts and all of that.

KLASZUS: Reader Rock Garden just north of Union Cemetery is William Reader’s restored homestead. As parks superintendent, he was given a few acres of land and a cottage by the city.

The land, which was a treeless hill back then, was transformed into a lush and tree-filled garden by the time his tenure ended in 1942.

DALKIN: Because he was a teacher by profession, he decided: Let’s make this area where we’re sitting at right now, which was his home, as an experimental site to basically be a living classroom. So he tried to bring all sorts of plants and trees, and let’s see if it can grow here.

KLASZUS: Over the years William Reader would bring about 4,500 new species of plants to Calgary, including the Colorado blue spruce tree. The first of its kind was planted right beside his house. Today, you can find it all over the city.

From tree-lined streets to car-friendly cul-de-sacs

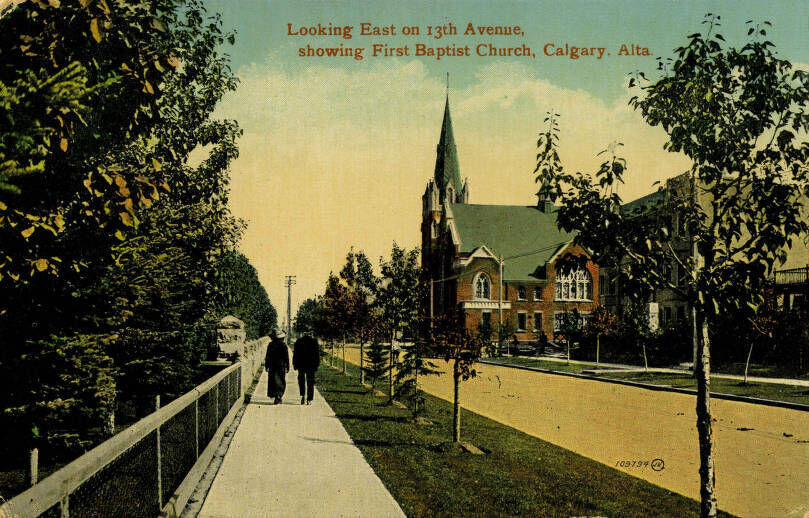

Just like William Pearce, William Reader also envisioned a city of trees. Like Pearce, Reader was strongly influenced by the City Beautiful movement of the day, which emphasized civic grandeur and leafy streetscapes.

MEGHAN LETT: And so can you tell me, if you’re going around the city today is there anything you can see of his influence?

DALKIN: Totally. Actually, there’s a lot of older communities, like in Sunnyside or even along Elbow Drive... the medians, you’ll notice that there are lilacs planted there. There’s caraganas. There’s various things. He wanted to add that to the landscape. So there are lots of places all along Memorial Drive, those big trees were also planted there for that very reason.

KLASZUS: Part of Reader’s legacy is 27 heritage streetscapes that were planted under his direction. These include streets where green ash and elm trees were planted between the sidewalk and the road, creating a big tree canopy over the street. You can see this in neighbourhoods like Crescent Heights and Mount Royal. The city has a conservation plan in place to protect these old streetscapes. If a plant needs to be replaced, it has to be with the same type of plant.

KLASZUS: Grid-pattern streets with tree boulevards used to be the norm. But after World War II, that changed.

BEVERLY SANDALACK: It was a lot of different forces and factors that combined.

KLASZUS: This is Beverly Sandalack, a professor at the University of Calgary’s school of architecture, planning and landscape. She’s also a landscape architect.

SANDALACK: The planning models changed. So rather than going with a more traditional kind of urban pattern, [it moved to] the idea of making places more self-contained neighbourhoods with cul-de-sacs and crescents. And a neighbourhood could be defined by collector roads around the outside. But it was really one coherent neighbourhood, rather than the city just going on block by block by block.

KLASZUS: The car was increasingly shaping the city. Cars move more efficiently on larger roads, and anything you add to a street—like trees—tends to slow them down.

SANDALACK: So getting rid of the tree boulevards was one way to give more priority to car traffic and less to pedestrian traffic.

SANDALACK: Another shift was economic. The city, for various reasons, decided that they weren't going to be responsible for the street trees—they would transfer that to the developer.

And so the developer, rather than planting a row of street trees in a treed boulevard, they were now giving two or three trees per lot in the front yard for a residential owner. So if you go into a neighbourhood that has the old pattern, there’s a continuous row of trees along the street that provide that canopy. There’s shelter, there’s shade, there’s habitat for birds and pollinators and so on that’s really continuous.

KLASZUS: But in many of the post-war communities, it looks different.

SANDALACK: The trees are set back and you don’t get that same feeling of the street enclosure. There’s a much different kind of habitat created. So you get a kind of patchy urban forest.

Getting rid of the tree boulevards was one way to give more priority to car traffic and less to pedestrian traffic.

A sweltering ‘urban heat island’: Tree inequity in Calgary

KLASZUS: At the start of this episode, I talked about how, when it’s hot out, you look for a little shade. And you might not realize that it’s warmer in the city than it is just outside Calgary.

Cities are urban heat islands, which means they stay a few degrees hotter than surrounding rural areas. Surfaces like concrete and asphalt absorb heat during the day and then feed it back into the air at night.

FRANÇOISE CARDOU: Cities are deeply modified environments where we’ve done a lot of things to the landscape to make them work for us.

KLASZUS: This is Françoise Cardou, an assistant professor and ecologist at the University of Calgary.

CARDOU: We’ve modified the landscape oftentimes by making soils impermeable, which means water can’t get through, and just building out a lot of concrete. And so trees—and really nature in general, but trees because they’re so big and they have so much biomass—can really help with a lot of the kind of collateral damages that we’ve done to our own environment.

Cities are urban heat islands, which means they stay a few degrees hotter than surrounding rural areas.

KLASZUS: Trees help mitigate the heat island effect by reflecting sunlight back into the atmosphere. They also evaporate water from their leaves, which helps cool the air. And they remove carbon from the atmosphere, which is why doubling the tree canopy is part of Calgary’s climate strategy to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

CARDOU: They have important roles to play in terms of soil stabilization, controlling erosion, especially along waterways. And they can help with water management because they have to be in permeable soils. And so they can help mitigate flooding and other things.

If you think outside of these very material benefits, they also do a lot for just our general mental health and wellbeing.

KLASZUS: Studies have found that trees can help alleviate depression, anxiety and stress. They can even decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease. And so with all the environmental and health benefits, it’s no wonder we’re trying to grow more of them.

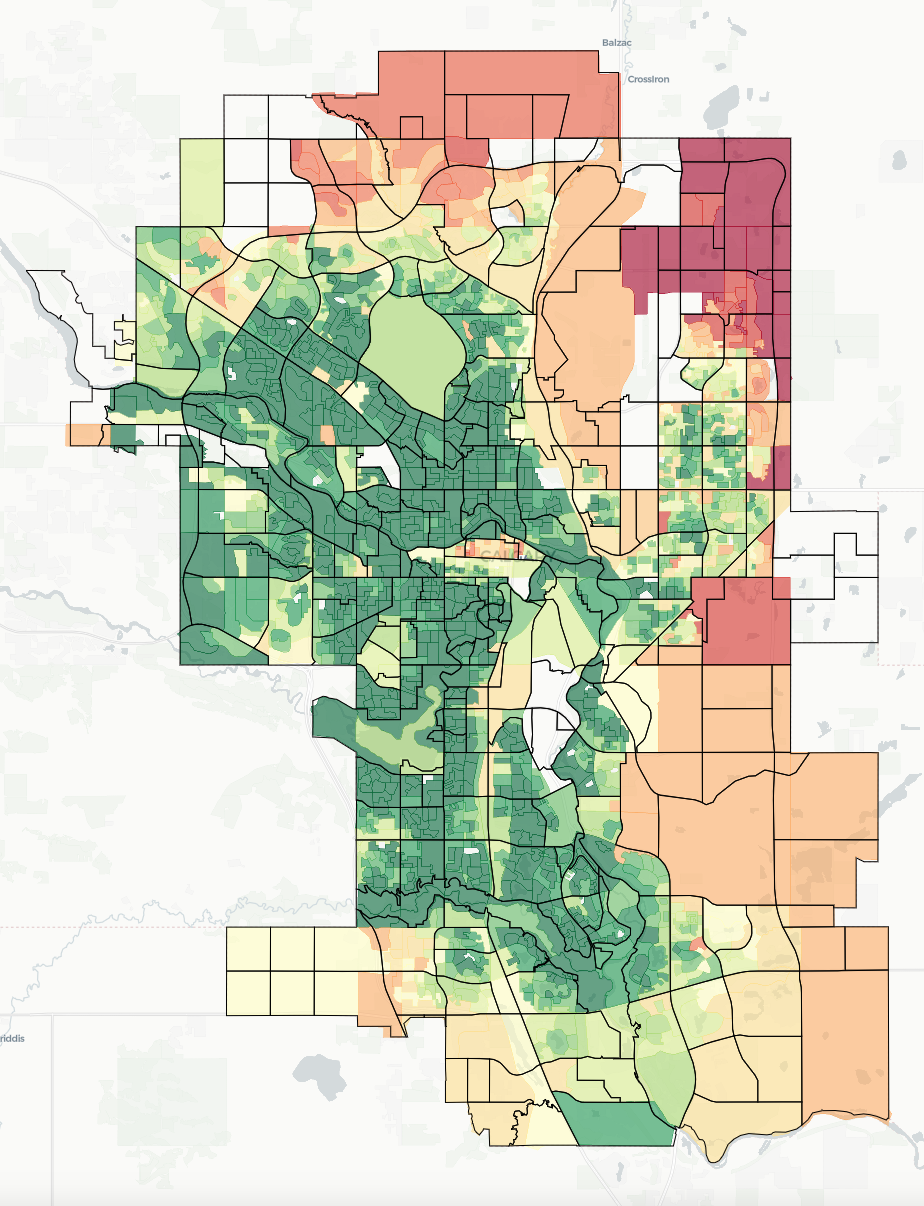

But these benefits aren’t available to all. The Calgary Climate Hub has created a Tree Equity Map, where you can see the percentage of canopy that covers different parts of the city.

KLASZUS: In inner-city neighbourhoods that have those historic tree-lined boulevards, there’s lots of canopy, often over 20%. But in neighbourhoods further out, there is far less cover—less than 1% in new neighbourhoods like Yorkville, Seton and Cornerstone. Tree equity is lowest in the city’s northeast, according to the Climate Hub’s map.

COUNCILLOR RAJ DHALIWAL: Often I hear it’s soil quality, it’s topography. Sure, but we are in 2024 here, and I'm pretty sure there’s tree species that can survive in that topography and those grasslands.

KLASZUS: This is Ward 5 councillor Raj Dhaliwal speaking to reporters in 2024.

COUNCILLOR DHALIWAL: It was Nature Canada that came out with a report, and they made a good argument and correlations that it has lots to do with demographics.

KLASZUS: The 2022 Nature Canada report he’s referencing (Canada’s Urban Forests: Bringing the Canopy to All) looks at how marginalized neighbourhoods in Canadian cities have less trees than those in affluent neighbourhoods. “Census areas of higher racial diversity often have a relatively low urban forest coverage in Calgary,” the report states.

It also mentions something called the 3-30-300 rule. And here’s what that means. Everyone should be able to see three trees from their home, neighbourhoods should have a 30% tree canopy and everyone should have a green space within 300 meters of their home.

If you think outside of these very material benefits, they also do a lot for just our general mental health and wellbeing.

COUNCILLOR DHALIWAL: If you look at Mount Royal, household income is much higher than my ward, and tree canopy is 30%. My ward, household income is lower and it’s reflected in the tree canopy. So some people call it environmental injustice, racism—I don’t know, I’m not gonna... but I think more could be done. The best area and community in my ward is Castleridge—9.39% tree canopy, not even in the double digits.

KLASZUS: One way the city is increasing the tree canopy is through the federal government’s 2 Billion Trees program. Calgary is receiving about one million trees from the program, and has already planted about 200,000 of them.

On private land, the city tries to encourage tree-planting with its Branching Out program, which gives a limited number of free trees to Calgarians. The trees are distributed by quadrant, with more trees for areas with a smaller tree canopy.

Droughts, snowstorms, chinooks: The myriad threats to Calgary trees

But just putting trees in the ground isn’t mission accomplished. They still need care to grow. And Calgary has some specific challenges.

KEVIN LEE: Calgary has something that a lot of other places don’t have. And what I’m talking about, of course, is the chinook. And the chinook can be problematic. Plants do like to go into dormancy in the fall, and if they can, they really like to just stay there. “Don’t wake me up when I’m sleeping, I’ve got shiftwork in the morning, for god’s sake!” So they just don’t like that. And it can disrupt the dormancy pattern.

KLASZUS: Calgary also has the unpredictability of harsh winter weather. An example of this is September of 2014, when Calgary was hit with a freak summer snowstorm, dubbed Snowtember. It damaged about half of the trees on public land, with many more on private land damaged as well.

Only about one in four trees in Calgary is on public land. The other three quarters are on private land.

Even though Snowtember was over a decade ago, the tree canopy hasn’t fully recovered. The tree canopy coverage was at 8.5% before Snowtember and today the city pegs it at around 8.25% (last measured in 2022). And the challenges continue through all seasons, as Calgary is prone to droughts in the warmer months.

LEE: When we have a drought pattern that sort of went away in 2024, but was powerfully strong and in place, locked down ’23, ’22, ’21... These were tree killing years. They really were.

KLASZUS: Because three out of every four trees are on private land, that means the amount of water they receive during droughts is up to their owners. The city takes care of the rest. But not everyone is happy about how the city is caring for its quarter of the urban forest.

LEE: You know, Calgary, and I mean the City of Calgary—you guys, you’re trying, but you’re not getting it. And you’re not even maintaining what you’ve got, okay? Truth be told. And you’re spending millions of our dollars and literally throwing it away. And the cost of having you guys grow, move and plant them is as high as possible because you’re not efficient.

I love all the propaganda and the language and talk, but let’s put some backbone and some shovel behind it. You’ve got to maintain what you’ve planted. Watching those super expensive little trees dry up and die in boulevards, parks, and new plantings is very, very sad.

The City of Calgary — you guys, you’re trying, but you’re not getting it. And you’re not even maintaining what you’ve got.

KLASZUS: We asked the city about these dying trees. Here’s urban forestry lead Paul Atkinson.

ATKINSON: I understand that perspective. I understand there’s maybe a bit of observation bias that’s sort of baked in when you see some of the trees that are struggling. So we do connect with a lot of trees in the year.

This was a difficult one last year, given the water crisis. But we were able to pivot and access non-potable water to water some of the public assets to keep them alive. So we try to water trees for five years after installation, and we have sort of a declining schedule as they acclimatize to their environments. We’ll perform like 300,000 site visits a year for watering events.

KLASZUS: This is the struggle of the 16% canopy goal. Even with new trees being planted on both public and private land, the percentage doesn’t grow if the same amount of trees die. There are a number of neighbourhoods in Calgary with poplars reaching the end of their life cycle. And where these are on public land, Atkinson says the city is trying to replace them with longer-living species.

We try to water trees for five years after installation, and we have sort of a declining schedule as they acclimatize.

Inner-city redevelopment also takes a toll on the tree canopy, as old trees get cut down for infill housing. This is a constant tension as the city tries to grow its tree canopy but also densify.

ATKINSON: We have to make sure that we also prioritize the people in the city. They need homes, and we’re trying to give them nice trees along the way as well.

Thinking small: Embracing the mini forest

KLASZUS: These are big challenges. But when it comes to Calgary’s urban forest, one way to grow more trees is to think small.

HEATHER ADDY: We see the mini forest as one way the city can reach that canopy goal.

KLASZUS: This is Heather Addy, a retired plant biologist. She’s part of the Calgary Climate Hub’s Forests for Calgary project.

ADDY: The goal of the Forests for Calgary program is to plant mini forests, also known as Miyawaki forests, in Calgary—with a priority as much as we can to plant in the northeast, where we have the lowest tree canopy cover in the city.

MEGHAN LETT: And so can you tell me what the mini forest method is?

ADDY: A mini forest is following the method developed by Akira Miyawaki, a plant ecologist. And the Miyawaki method—I’m just going to call them mini forests because it’s easier, but it’s planting very dense plantings in a small area. So, it’s about 200 m2 typically, which is roughly the size of a tennis court.

KLASZUS: When planting a mini forest, you choose hardy plants that are typical of a later stage in the development of a forest. And it’s not just trees. They plant all the layers of a forest, which includes other plants like shrubs and wildflowers. And this, coupled with the dense planting, creates what Miyawaki called “virtuous competition.”

ADDY: So they’re going to compete with each other for light, they’re going to grow upwards very quickly, so you get a forest developing in decades rather than hundreds of years.

KLASZUS: Since 2022, the Climate Hub has planted four of these mini forests—including two in northeast Calgary, in Marlborough and Martindale.

ADDY: The heart of the Miyawaki method or the mini forest method is community. So you involve the community at all stages. You engage people with planning, and designing and planting, and then looking after the forest.

ADDY: The planting days are quite something because it’s a small area, and we usually have 60 to 80 people, sometimes more, all trying to plant at the same time in these little areas. It’s a really fun and positive event, because everybody feels like they’re doing something positive and creative for their community, and hands-on making a difference.

KLASZUS: Doubling Calgary’s urban forest is a big goal. So is growing that forest equitably. Addy says that in order for that to happen, everyone will need to pitch in.

ADDY: It’s a huge task, and it’s more than any one organization or unit of the city or household can do. We all have to pull together to say this is something we want for our city.

Meghan Lett is a Saskatoon-based journalist who reported and wrote this story while completing her journalism diploma program at SAIT.

With files from Jeremy Klaszus.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!