Photo: Gavin John

Undermined: The long fight over Canmore’s future

Before tourism, coal mining drove the town.

Sprawlcast is Calgary’s in-depth municipal podcast. Made in collaboration with CJSW 90.9 FM, it’s a show for curious Calgarians who want more than the daily news grind.

This Sprawlcast is a collaboration with The Narwhal, an independent news outlet that dives deep to tell stories about the natural world in Canada. Drew Anderson contributed reporting and research for this story. You can read his article on the Three Sisters saga here.

This is the first episode in a Sprawlcast series. The second episode, on the town's resistance to Three Sisters, is here.

If you value in-depth Calgary journalism, support The Sprawl so we can do more stories like this one!

JOHN SNOW JR.: Our creation story begins in these mountains.

SARAH ELMELIGI (MLA): A provincial body forced the town of Canmore to approve an unwanted development.

MAYOR SEAN KRAUSERT: I think that it has been painful for everyone involved.

JEREMY KLASZUS (HOST): In the spring of 2021, Canmore town council had a big decision on its hands. At issue was a controversial plan for a new housing development across from Dead Man’s Flats, about 10 kilometres east of downtown Canmore. The developer was Three Sisters Mountain Village, and the project, called Smith Creek, would nudge out a small part of the town’s urban growth boundary. Let’s listen in to that council meeting.

MAYOR JOHN BORROWMAN: I am concerned by the requirement to move the urban growth boundary at this time.

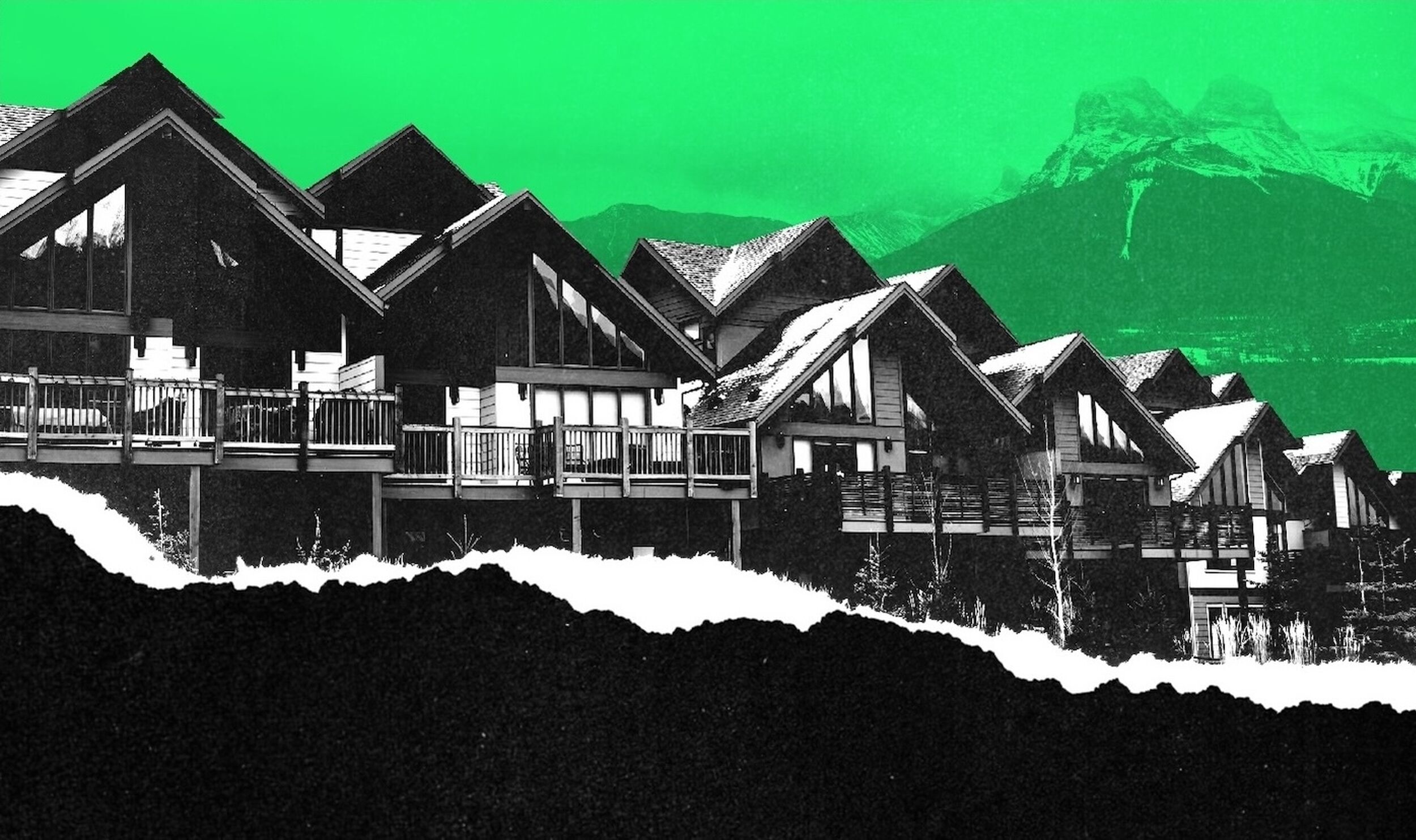

COUNCILLOR JOANNA McCALLUM: I see a residential footprint that will reflect trophy homes moving into the future. And I don't feel that that is the housing that Canmore needs.

COUNCILLOR ESMÉ COMFORT: I won't be able to support this either, for the reasons already cited. The urban growth boundary is almost like a sacred barrier. And we don't open it before we absolutely need to.

KLASZUS: Town council unanimously voted “no” to the Smith Creek plan. A month later, council voted on plans for a second Three Sisters development closer to town.

660 NEWS: Canmore town council has rejected a second proposed development project. The Three Sisters Village and Smith Creek projects would have almost doubled the town's population in the coming decades.

KLASZUS: But that’s not the end of this story—far from it.

Later in 2021, Three Sisters Mountain Village filed a $161 million lawsuit against not only the Town of Canmore, but also individual council members who voted down the plans. A few months later, a provincial tribunal overturned council’s decisions, ordering the town to approve the developer’s plans in order to align with a provincial decision from the early 1990s.

So that’s what council did in October of 2023. But it didn’t end there.

In December, the Stoney Nakoda Nations sued the town and the province for approving the plans, citing the Nations’ rights under Treaty 7 and the duty to consult. The Stoney Nakoda say the Three Sisters plans will further encroach onto their traditional territory, stress an already fragile environment, and further fragment wildlife habitat.

I’ve heard bits of news about this Three Sisters development as it’s started and stopped and started again over the years. And especially lately, I’ve been wondering: What in the world is going on in Canmore?

This Sprawlcast series will dig deep into that question. This series is based on decades of documents and news reports, years of public meetings and more than two dozen interviews.

It’s a story about how power and politics have transformed the Bow Valley. It’s a story about local democracy and its limits. It’s a story about what happens when different values and visions for a place collide.

And there’s a lot more to this saga than you see on the surface.

Canmore's coal mining roots

To understand the situation in Canmore today, we need to go back before the colonization of the West. The Bow Valley and surrounding mountains were home to the Stoney Nakoda people, or lyârhe Nakoda, long before white settlers arrived in this part of the world.

JOHN SNOW JR.: I am John Snow, Jr., descendent of the Treaty 7 signer, Chief Goodstoney.

KLASZUS: This is Snow speaking at a public hearing about the Three Sisters project in 2021. The Goodstoney First Nation is one of three bands that comprise the Stoney Nakoda Nations, along with the Bearspaw and Chiniki. And the Canmore area is important for all three lyârhe Nations. lyârhe Nakoda means “people of the mountains.”

SNOW JR: These mountains are our sacred places. We have many concerns with developments in the Bow Valley. These areas are our traditional and cultural areas.

KLASZUS: In the 1970s, Snow’s father, Chief John Snow, wrote a history of the lyârhe people called These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places. In the book, he describes how the treaties were misused by the Canadian government to open the land to white settlement and commercial exploitation—and close it off to its original inhabitants by confining First Nations on reserves.

These mountains are our sacred places. We have many concerns with developments in the Bow Valley.

SNOW JR.: Through the Indian Act and other legislation, we were prohibited from many human rights in Canada, including worshipping in our sacred places. Canmore is one of our sacred places. For many of our people, we have been denied access to hunt, fish, gather, harvest in these and other traditional and cultural spaces for our Indigenous spiritual practices.

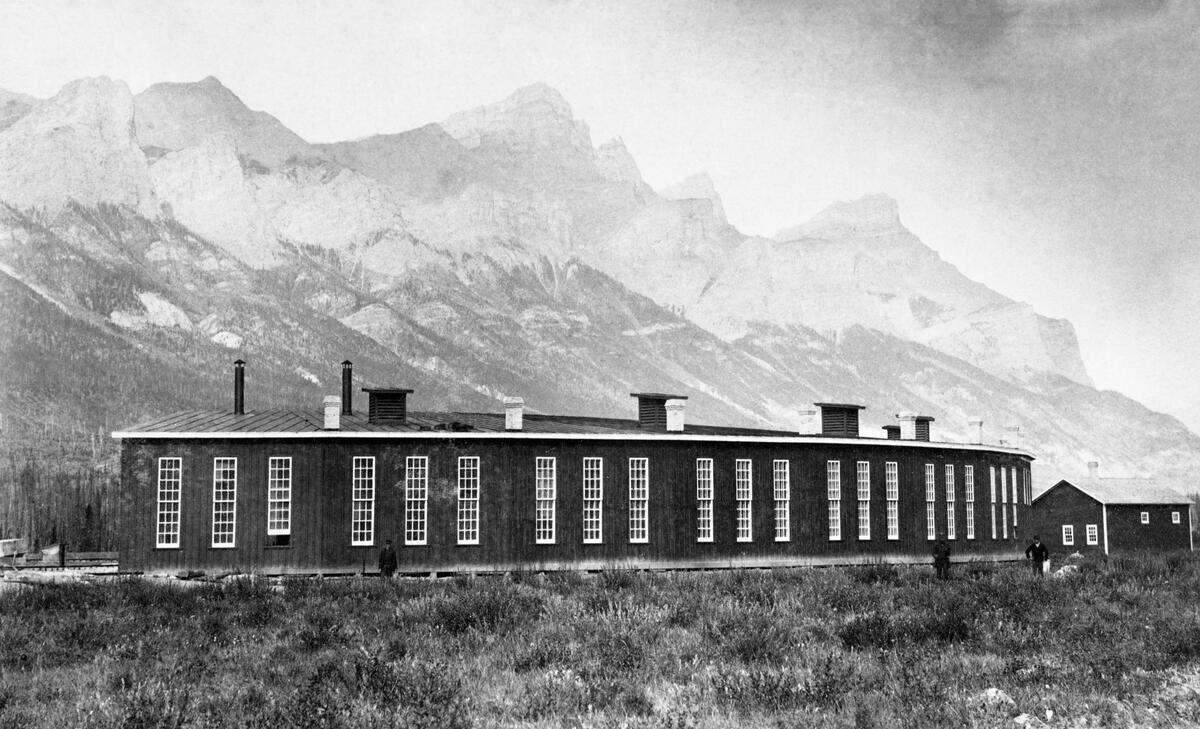

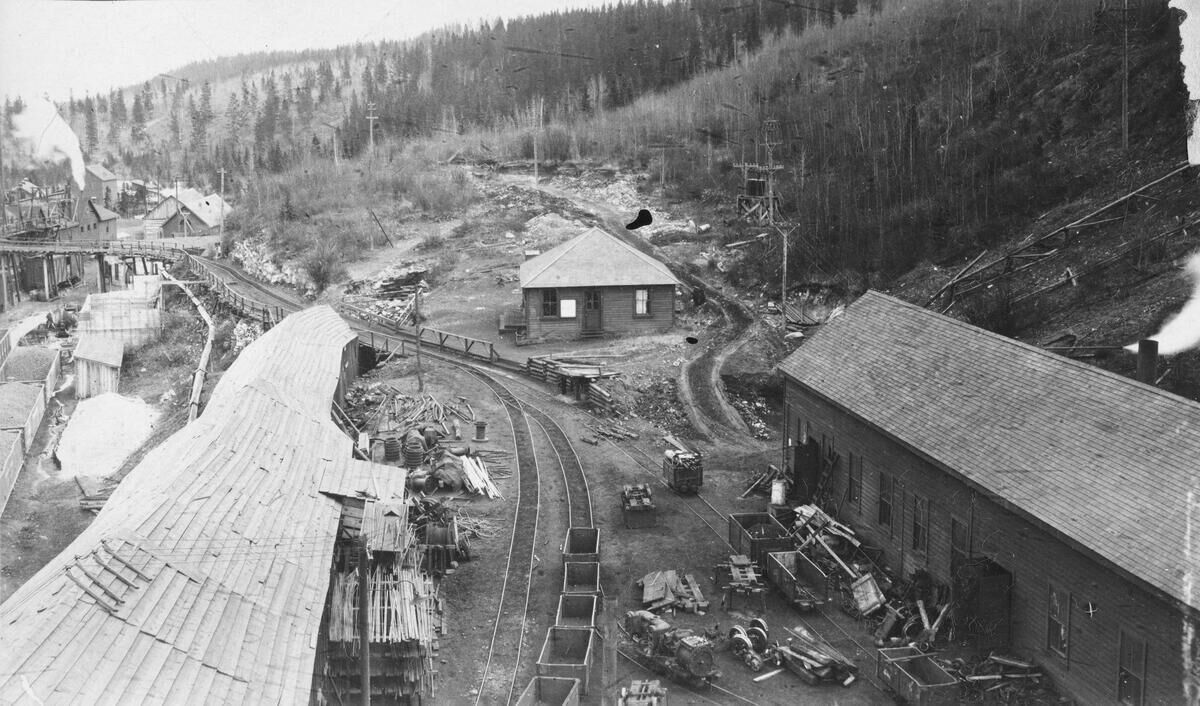

KLASZUS: The westward construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s filled the West with European immigrants and enabled the extraction of natural resources. The CPR established a railway depot at Canmore in 1883, just six years after the signing of Treaty 7. And Canmore was quickly established as a mining town.

RAYMOND HAIMILA: My grandfather started work in the No. 1 Mine in 1907. My dad started work in the No. 2 Mine in 1926.

KLASZUS: Raymond Haimila grew up in Canmore and worked jobs in and around the mines as a teenager.

HAIMILA: When I was 15, we used to shovel coal into the boilers, and we got paid a dollar a ton. The boiler heated the Y, the mine office, the post office, the movie theatre, and a couple of the other small buildings. And the Rundle Mountain Trading Company, which was the mine company store.

KLASZUS: Haimila remembers the Canmore Hotel on Main Street being a lot more rowdy than it is today. Especially if a CPR railway gang was in town.

HAIMILA: Mining town, one bar. The Canmore Hotel. Everybody’d be in there. So by about nine o’clock at night, somebody would fly out through the window. And it was usually a fellow by the name of Bodner threw the first guy out the window. And we’d sit there and watch, and see all the fights come out. The miners always won.

KLASZUS: To ride around town with Haimala in his Volvo is to get a tour of the town’s coal mining history.

HAIMILA: In the ’60s, all these lots here were sold for $50 to the miners. And I helped pour the concrete into all these basements, all through these houses here, because these were all little mine houses at one time. None of these stuff.

KLASZUS: Most of the mine houses are long gone.

HAIMILA: They tear down a house and put up a monster. But they’re selling these for a million dollars, and they’re building a two million dollar house. And the majority of miners never got the benefit of it.

KLASZUS: For nearly a century, coal mining was a core part of Canmore’s economy and civic identity.

HAIMILA: If you’re on day shift, you start work at eight o’clock. People would be at the mine at 5:30, at the wash house to change, because people loved going to work. I never was ever on a job where everybody enjoyed their work so much. They looked forward to going to work underground. It was amazing.

KLASZUS: Canmore’s semi-anthracite coal was particularly valuable for manufacturing steel. And its lure went far beyond the CPR railway. Japanese companies were buying hundreds of thousands of tons of Canmore coal by the 1950s.

HAIMILA: There were only two mines in North America that had that type of coal. One was here, and one was in Pennsylvania. And that’s why Japan wanted all that coal, because it was so good for the steel industry.

KLASZUS: Canmore didn’t draw a lot of outsiders back then. You wouldn’t drive from Calgary to spend time there like people do today.

HAIMILA: People didn't like to stop in Canmore. It was a mining town. They felt nervous here. They would rather just go straight to Banff because mining towns had a bad reputation, I guess.

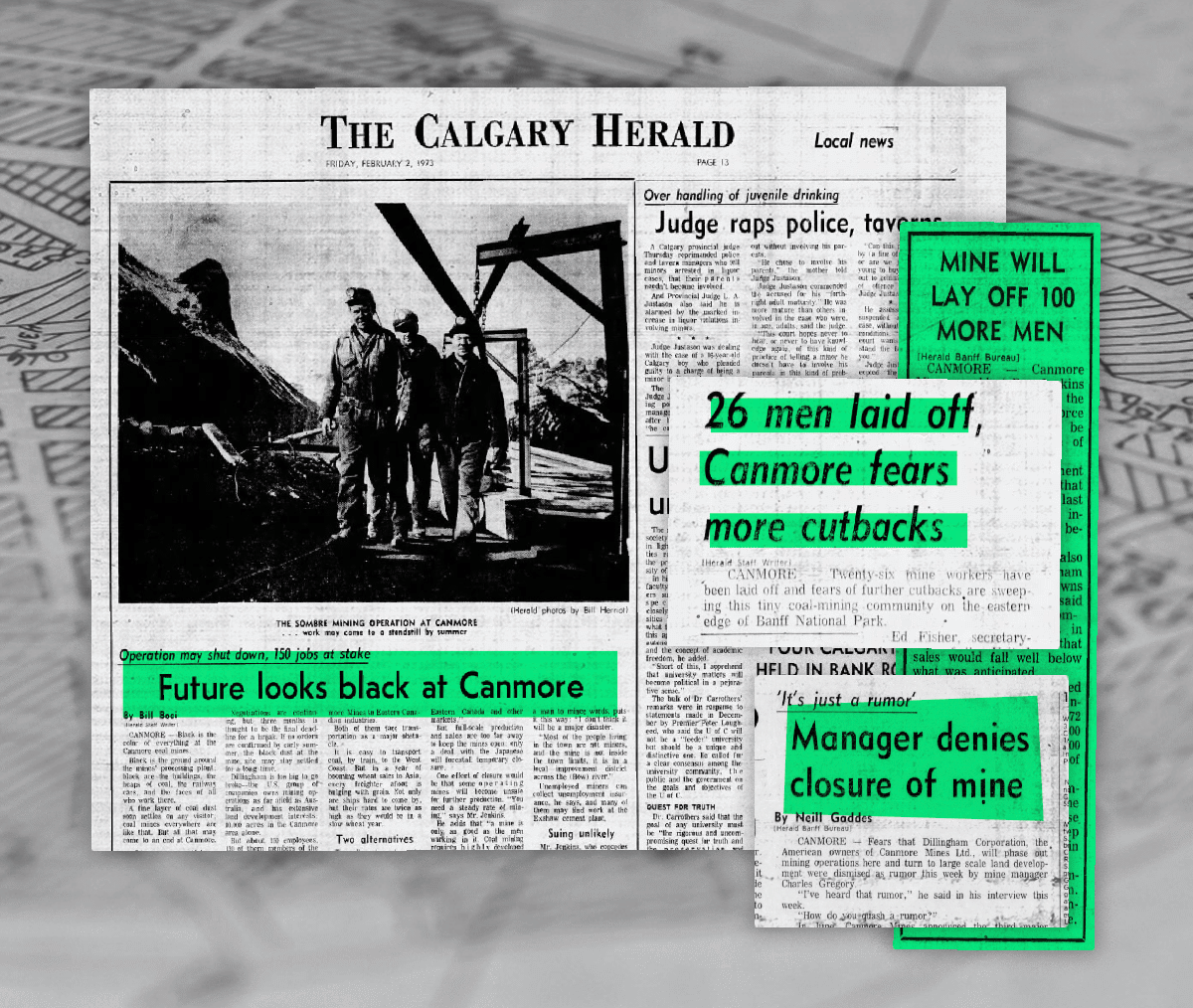

KLASZUS: In 1971, a Hawaii-based conglomerate called Dillingham Corporation bought the Canmore Mines. And the ’70s were not kind to Canmore. Coal markets were fluctuating and Japanese companies were buying less Canmore coal. Miners got laid off.

The town’s future looked increasingly uncertain.

KLASZUS: But speculators saw a new business opportunity in what was then called the Canmore Corridor: tourism. The Canmore Corridor was appealing because it didn’t have the development restrictions of Banff National Park to the west.

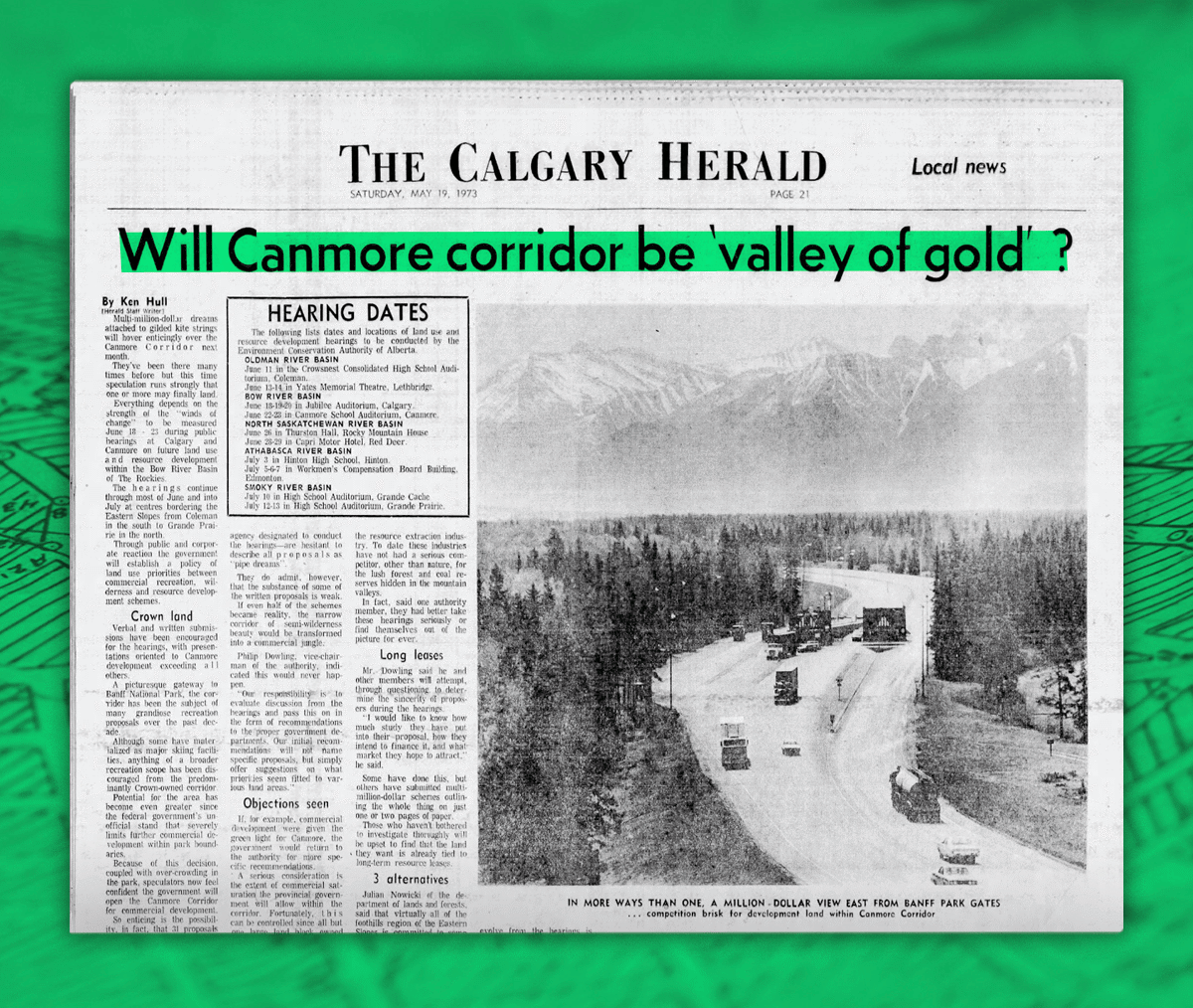

In 1973, the province held land use public hearings for the corridor. The Calgary Herald reported that 31 proposals were put forward by “individuals and groups eager to cash in on what might become Alberta’s Golden Valley.”

“If even half of the schemes become reality,” noted the Herald, “the narrow corridor of semi-wilderness would be transformed into a commercial jungle.”

KLASZUS: But there was a hitch. Most of the Canmore Corridor was Crown land, owned and controlled by the province. The speculators were hoping the government would sell it off. But of all the companies with designs on the corridor, Dillingham alone owned land in the area.

HAIMILA: They wanted to develop this as a resort.

KLASZUS: Dillingham initially denied rumours that it was interested in building a resort. But at the 1973 hearings, the company floated the possibility of developing a golf course, artificial lakes and 3,000 housing units. Not right away, but decades in the future—maybe 50 years away.

People didn’t like to stop in Canmore. It was a mining town. They felt nervous here.

The 1988 Winter Olympics come to town

KLASZUS: Dillingham closed the last Canmore mine in the summer of 1979, on a day that became known locally as Black Friday.

HAIMILA: When the mine shut down, so many people thought there was no future here, and a lot of them left.

KLASZUS: But two years later, in 1981, the International Olympic Committee made a big announcement in West Germany, as CBC reported at the time.

IOC OFFICIAL: …Reviendra à la ville de Calgary. [cheering and clapping]

FRANK KING: After 30 years—at last we've got it. Hallelujah!

KLASZUS: This is Frank King, the CEO of Calgary’s 1988 Olympic committee.

KING: It's going to change the future of Calgary. Calgary will become now an international city.

RALPH KLEIN: Beyond sport, it means that Calgary has gained its place in the international world. It is now, not only a financial centre and an oil capital, it is an Olympic capital.

KLASZUS: That was Ralph Klein, who was mayor of Calgary at the time—before becoming Alberta’s environment minister and premier.

The 1988 Winter Olympics wouldn’t just change Calgary’s future. The Games would dramatically change Canmore, too.

ABC TV CLIP: And below the Nordic Centre here in Canmore, what was once an old mining town is turned into a winter carnival. The Nordic Centre was built at a cost of 15.4 million dollars. Needless to say, it’s a state-of-the-art facility.

KRISTY DAVISON: It went from being a really sleepy, sleepy town to that excitement of the Olympics coming to town.

KLASZUS: This is Kristy Davison. She’s a local publisher who grew up in Canmore.

DAVISON: I remember that vividly, that feeling of the torch is coming. We get to hold the torch! Oh my gosh, all the little jackrabbit cross-country skier kids—we get to release the balloons at the opening ceremony of the Olympics!

HAIMILA: That was big time. That put Canmore on the map, for sure. That really started the property values going up. People from all over the world started to buy properties here.

It went from being a really sleepy, sleepy town to that excitement of the Olympics coming to town.

KLASZUS: The Winter Games weren’t the only outside force transforming the town. In 1980, Peter Pocklington, the millionaire owner of the Edmonton Oilers, bought the Canmore Mines land from Dillingham, just as Wayne Gretzky completed his rookie season in Edmonton.

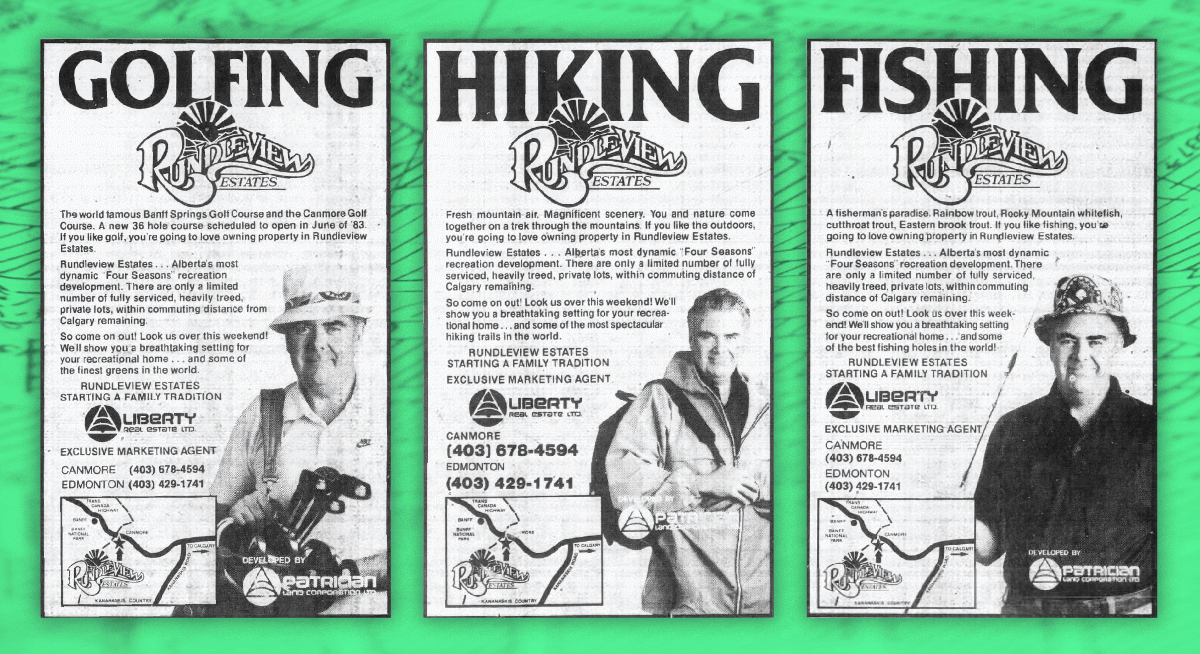

Pocklington’s company, Patrician Land Corporation, had bought the Canmore Mines land for residential and resort development. The land stretched along the Bow Valley from Canmore to Dead Man’s Flats. And in 1981, construction started on the western end, with 140 single-family lots in town called Rundleview Estates.

KLASZUS: For the eastern end, Pocklington’s company proposed a sprawling resort project. The idea was to build condos, hotels and golf courses, echoing a resort in Vail, Colorado. In fact, that was the project’s working name: Echo.

But the project soon went into receivership—and it wouldn’t be the last time. Ownership of the Three Sisters lands has changed numerous times since.

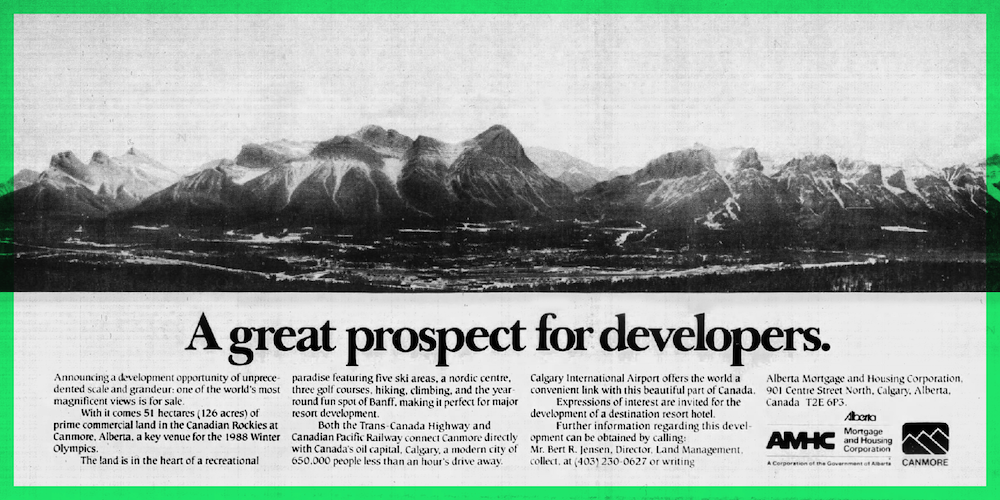

Meanwhile, other speculators were getting their wish as the Alberta government sold off other Crown land in the Canmore corridor. In 1985, the government advertised in newspapers around the world, including the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times of London, that “one of the world’s most magnificent views is for sale.” This was the land on the north side of the highway by Canmore—which has since been developed.

KLASZUS: In 1989, the old Canmore Mines lands were purchased out of receivership by “a group of powerful and politically well-connected Calgary businesspeople,” as the Herald put it. The NDP decried them as “cronies” of Alberta’s conservative government.

One of the new owners was Frank King, the Calgary Olympic committee CEO. Another was Bill Dickie, who was Alberta’s mining minister in the ‘70s. And there was also Richard Melchin, who’d been president of Pocklington’s land company. (His brother, Greg, would become a Conservative MLA in 1997.) Their new company was called Three Sisters Golf Resorts, named for the mountain that looms over the property.

RON CASEY: Certainly in the late ’80s, early ’90s, there was almost the sense of being under siege.

KLASZUS: This is Ron Casey. He moved to Canmore in 1973. He became Canmore’s mayor in the late ’90s and was also a Conservative MLA after that.

CASEY: You had people coming in that had way more capacity than anyone locally had ever dreamt would show up on our doorstep. And there was a bit of a concern, I’d say in the community, that we were being outweighed. That these people were all politically connected. That they had way more capacity to deal with the province to manipulate, if you like, some of the outcomes that the community wouldn’t have the same say in.

In 1989, the lands were purchased by ‘a group of powerful and politically well-connected Calgary businesspeople,’ as the Herald put it.

KLASZUS: Canmore was growing fast. When the mine closed in 1979, Canmore had a population of 3,000. By 1992, that had doubled. The lands east of town that were once viewed as being for development one day, maybe, had now become the subject of intense focus.

CASEY: It was totally divisive. There was a construction industry that was just coming out of a recession from the middle ’80s, and so the construction industry was still hurting. There were people that were welcoming the idea of a major development coming in. But of course, then there was another side of the community that saw this as basically an attack on Canmore.

KLASZUS: The nature of housing in the Bow Valley was also changing. Planners believed Canmore needed more land not only for locals, but also “to meet the increasing demand in the community for recreational or second homes,” as one consultant report from 1990 put it.

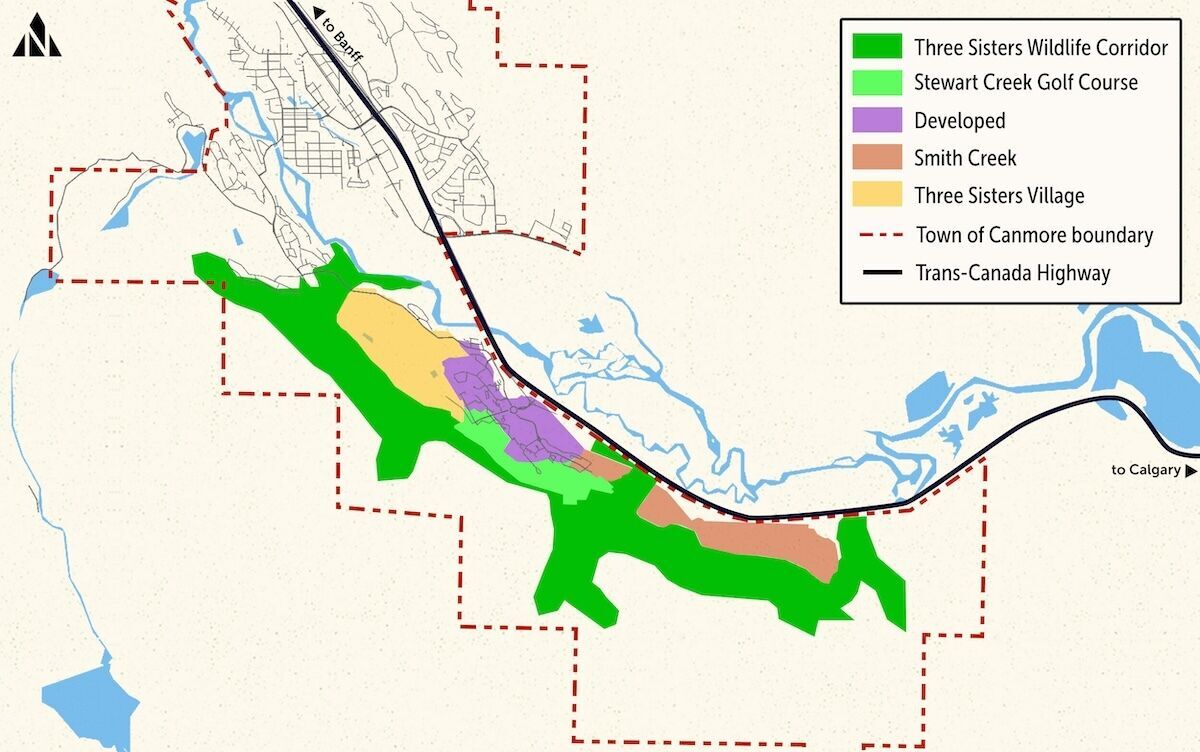

In 1991, the Town of Canmore annexed a big chunk of land east of town from the M.D. of Bighorn, including the Three Sisters properties. This was meant to be a 40-year supply of land.

MAYOR SEAN KRAUSERT: The lands in question were specifically annexed from the M.D. of Bighorn decades ago by the Town of Canmore for the purposes of future development.

KLASZUS: This is Canmore Mayor Sean Krausert speaking at council in October 2023.

KRAUSERT: They are private lands. And the question has never been if they'd be developed, but rather when.

A snapshot of Canmore today

Before we continue with our history, let’s consider the lay of the land in Canmore today.

The town has a population of about 15,000. And as a mountain town on the doorstep of Banff National Park, Canmore has the highest cost of living in Alberta. In 2020, the town’s median family income of $125,000 was just slightly higher than Calgary’s. But when it comes to the costs of housing, it’s a different story, even more unaffordable in Canmore than it is in Calgary—and the market is tighter.

Consider the differences in rent. For a two-bedroom unit, the average rent in Calgary was $1,460 in 2022. In Canmore, it was more than $1,900.

Canmore has another unique characteristic: its “non-permanent” population, people who have second homes in Canmore but their primary residence is elsewhere. According to the 2021 census, only 3 in 4 dwellings in Canmore were occupied by “usual” residents.

But the growing footprint of the town is eroding the wilderness that draws people here in the first place. This is Hilary Young, the communities and conservation director at the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative.

HILARY YOUNG: The Bow Valley is one of a few very important east-west connectors in this broader 3,200 kilometer region called the Yellowstone to Yukon region, which is one of the most intact mountain ecosystems remaining in the world.

KLASZUS: The corridor is important to species such as bears, cougars, elk and wolves.

YOUNG: The valley itself is flat and warm and relatively wide compared to other adjacent valleys. And there’s a river running through it, so the vegetation is great—good habitat. Much of that sort of core valley bottom habitat is taken up by people and developments and roads and highways and railways. And what’s left are these sort of swaths of land on either side of the valley for wildlife to move through the Bow Valley, and keep populations well connected.

The ultimate risk is that wildlife who have used this valley and this habitat for thousands of years may no longer come to this valley.

YOUNG: This Three Sisters development—it’s really going to be moving up into one of the remaining corridors that is allowing animals to move between Banff National Park and Kananaskis Country. The corridor that remains is steeper than animals prefer. Most animals like more shallow sort of angles and slopes. And the topography is a little bit rocky, and there’s going to be less food availability, and we just know that it’s not preferred by animals at all for movement through there.

Not to mention the challenge of adding up to 14,000 more people right adjacent to a corridor, in an area where there currently aren’t anywhere near that many people.

So we are worried about human-wildlife conflicts going up, and the ultimate risk is that wildlife who have used this valley and this habitat for thousands of years may no longer come to this valley.

The landmark 1992 decision

In 1992, former Calgary mayor Ralph Klein became premier of Alberta. That year would be a pivotal one for Canmore.

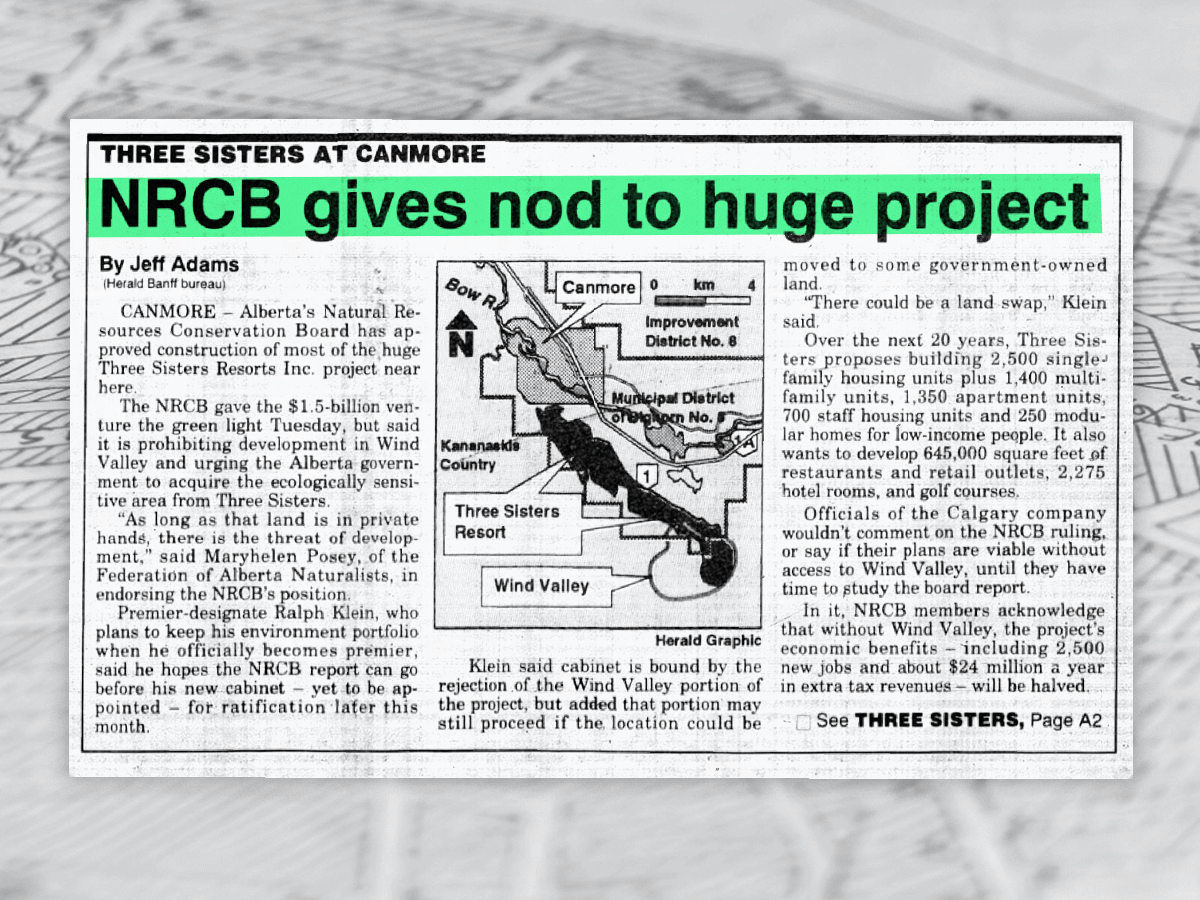

A couple years earlier, in 1990, Alberta’s Conservative government had created a new quasi-judicial tribunal called the Natural Resources Conservation Board, or NRCB. Its mandate was to assess non-energy development projects. And in an echo of Pocklington’s failed effort, Three Sisters Golf Resorts had applied to the NRCB to build a “recreational and tourism project” with hotels, golf courses, housing and commercial development.

From the get-go, the Canmore case was a weird one. Normally, municipal councils are responsible for making decisions on developments within towns and cities. But because Three Sisters Golf Resorts had applied for “a recreational and tourism project,” rather than a purely residential development, it fell under the jurisdiction of the newly-created NRCB.

And the NRCB has long since become part of Canmore town lore, alongside the 1988 Olympics.

KRISTY DAVISON: You do grow up knowing that that acronym in this town, even if you don't know what it means. The NRCB had said this land is going to be developed.

KLASZUS: Kristy Davison is the publisher of Mountain Life Rocky Mountains magazine. She remembers that when she was a kid in the early ’90s, her mom was one of many Canmore residents organizing against the resort project.

DAVISON: My mom was at every meeting. She was active on every piece of it—the way I remember it anyway. She would try to explain it to me, but it was so complex. It’s complex to me now. As a 10-year-old, it was pretty incomprehensible.

The NRCB has long since become part of Canmore town lore, alongside the 1988 Olympics.

KLASZUS: In 2016, Davison started documenting the convoluted history of the Three Sisters project on an independent website called Canmore Commons.

DAVISON: I just found a lot of people asking me about it, and trying to ask me if I could explain it to them, and I realized I can’t. I cannot explain this because I actually don’t really know. I know it’s big, and I know it’s long, and I don’t know how to tell you what you need to know. So I just started to do tons of research.

KLASZUS: Davison and other Canmorites would soon discover just how far the 1992 decision reached.

In the early ’90s, Three Sisters Golf Resorts envisioned its resort project adding about 15,000 people to the town’s population, with 6,000 housing units and nearly 2,500 hotel rooms. At the NRCB hearings on the project, local groups and citizens raised a host of issues that would only become more pronounced in the decades ahead: wildlife habitat, affordable housing, Indigenous rights.

CPAWS and other environmental groups warned that the Three Sisters development would devastate grizzly bear populations. The Stoney Nakoda Nations called for an affirmative action hiring program if the project was to proceed. The local Women's Resource Centre warned that Canmore was starting to become a boomtown, and that women in boomtowns often experienced low wages and job insecurity, hampering their ability to pay high rents.

After weeks of hearings, the NRCB approved most of the Three Sisters application, citing the economic benefits. The board forbade any development in Wind Valley on the southeastern edge of the property, deeming it too sensitive ecologically. But it approved the part closer to town, with certain conditions.

KLASZUS: The board said the approval was meant to give Three Sisters “a reasonable degree of certainty of use but at the same time not usurp the powers of the municipal planning authorities.”

All of this would be interpreted very differently for decades to come. Here’s former Canmore mayor Ron Casey on what the province did next.

CASEY: By 1995, they had changed the Municipal Government Act and added Section 619, which was in those days called affectionately “the Canmore clause.”

KLASZUS: Section 619 prohibited municipalities in Alberta from blocking projects that had already been approved at the provincial level. Canmore’s mayor at the time, Bert Dyck, called it “an erosion of local authority,” and Casey echoes that concern today.

CASEY: There was no question that it was a political drive in Edmonton to ensure that this development went ahead.

CHRIS OLLENBERGER: This project falls into a category of provincial significance... It was deemed to be a project in the interest of the province. And so it has an order-in-council approval from cabinet that says this project will proceed.

KLASZUS: This is Chris Ollenberger, director of strategy and development for Three Sisters Mountain Village Properties, the current owners. Ollenberger is also a well-known Calgary developer—but we’ll get to that in a bit. Here’s what he says about Section 619.

OLLENBERGER: The intent behind it was, if the entire province kind of thinks it’s good from the provincial government point of view, that a more localized subset of individuals wouldn’t be able to say “but we still don’t want it.” We have to think at some point, just like the federal government makes decisions about the environment for all of Canada, there’ll be decisions that are made at a provincial level that will override municipal authority. Three Sisters is one of those projects.

KLASZUS: By the mid-’90s, the town and Three Sisters were already fighting in court over what exactly should happen on the Three Sisters lands—and who had the last word, the town or the province.

There was no question that it was a political drive in Edmonton to ensure that this development went ahead.

CASEY: From the developer side, they felt that when parts of the development were approved by the NRCB, that was a carte blanche, go ahead, do-anything-you-want scenario.

KLASZUS: Casey was first elected as a town councillor in 1995, and recalls it being a challenging time. Three Sisters was riding the Alberta boom-and-bust cycle that has plagued this project since its inception—the starts and stops as owners would unfurl big plans, but run into financial troubles.

CASEY: It was a very fractured community. Three Sisters really had not been able to get their feet under them and get going. And so, they were struggling, and we were struggling as a community because how do you sustain a place… Our concern as a community was that we were going to lose our identity. We were seeing our property values increase to a point where no one working locally could afford to live here. So, even in those years, it was a difficult place to find housing and to purchase it.

This project falls into a category of provincial significance.

KLASZUS: By the late ’90s, the town and Three Sisters hashed out a plan they could agree on.

CASEY: We’d gone to court, and all of that stuff. At the end of the day, we sat down and said, look, this is stupid. You guys—none of you will live long enough to see these court cases done. So, that doesn’t do anything for you, it doesn’t do anything for us, so surely to God, there’s a way for us to sit down and work through this.

KLASZUS: The result, in 1998, was a settlement agreement—a truce of sorts amid the acrimony.

CASEY: So we came up with a maximum number of dwelling units, maximum number of hotel rooms that were all involved in this settlement agreement, which was signed off on by Three Sisters and by the town.

No one was ever—I mean, there was the hardcore in Canmore that said “no development at all on Three Sisters.” But most of us knew something was going to occur there. It was a question of managing that something, so that we as a community could survive. That was really the underlying thing from the ’90s, was ensuring that unlike every other mountain town in North America, we would be able to sustain a local population of people. That people would continue to be able to live here, and afford to live here.

Most of us knew something was going to occur there. It was a question of managing that something, so that we as a community could survive.

The push for a wildlife corridor

JON JORGENSON: We were under a lot of pressure after the NRCB decision. Pressure from Three Sisters.

KLASZUS: This is Jon Jorgenson. He’s a former senior wildlife biologist for the province. Jorgenson retired in 2015, but in the 1990s he was working on this file.

He was on it because when the NRCB approved the project, it required Three Sisters to map out wildlife corridors on its property and get them approved by the province before building anything. And this requirement was quite unusual.

JORGENSON: Development approvals is not something that the provincial government is usually responsible for on private lands. That’s the responsibility of the municipalities and other levels of government. So for the provincial government to be the one to basically approve the location, and the width of the wildlife corridors on these private lands was something new.

KLASZUS: It was up to Jorgenson to advise senior government officials.

JORGENSON: Suddenly pressure came at senior levels that, hey, we need to get this corridor resolved. We need to get an approved wildlife corridor because we want to move forward. And we can’t move forward until we have a wildlife corridor. And for myself, what it meant was having to approve a wildlife corridor when we didn’t have adequate information, because we didn’t know very much about wildlife movement in those days.

We were under a lot of pressure after the NRCB decision. Pressure from Three Sisters.

KLASZUS: The province approved a wildlife corridor in 1998. But it soon became obvious that it was inadequate.

JORGENSON: Too much of it was on steep slopes, and it needed to be modified. But because we had to make a decision, basically, an approval was made when we didn’t have the necessary information to make the best decision. But that’s the way it was, and that’s what happened.

CASEY: It had no basis in science, and it took us years of fighting with the province for them to actually admit that, really, there was no science involved in it. It was political science, and only political science that had dictated where the wildlife corridors went.

KLASZUS: In 1999, a company called TGS Properties bought the land. Two of the people behind this company still own the project today, but through a different company.

One of these owners is Calgary businessman and philanthropist Don Taylor—the Taylor whose name appears on the Taylor Family Library at the University of Calgary, and the Taylor Centre for the Performing Arts at Mount Royal University. The other is Blair Richardson, a former Morgan Stanley executive who started a Denver asset management firm called Bow River Capital.

What it meant was having to approve a wildlife corridor when we didn’t have adequate information.

In 2000, Richardson declared that Three Sisters was the most important land development play in Western Canada. Chris Ollenberger says much the same today.

OLLENBERGER: The property is, I think, special and unique within Alberta.

KLASZUS: Ollenberger is another main character in the Three Sisters saga. He’s actually the second generation of his family to work on Three Sisters—his aunt also worked on this project in the ’90s.

Ollenberger was president of Three Sisters Mountain Village in the mid-2000s. But he left in 2007 when he was hired by the City of Calgary to oversee the redevelopment of East Village. While he was doing that, amid a recession, Three Sisters filed for bankruptcy in 2009—the second time that’s happened on this project.

In 2012, Ollenberger started a company called QuantumPlace Developments, which has done a bunch of redevelopment in the Calgary area, including a couple luxury housing projects in Canmore. In 2013, the Taylor family and Blair Richardson repurchased Three Sisters Mountain Village. And they brought back Ollenberger and QuantumPlace to manage the project for them.

OLLENBERGER: How many properties can you say are on the eastern ranges of the Rockies, within a pretty good valley, access within an hour of a major airport, access to a city of over a million people, easily accessible with about 45 to 50 minutes on the highway—and it’s the main nation’s highway traveling through this valley.

You stop there. How many people from Calgary say: I’m going to go skiing. I’m going to go cross-country skiing. I’m going to the Nordic Centre. I’m going to go hiking. I’m going to go mountain biking in Canmore or in Banff. And it’s on the gates of Banff National Park. There are very few opportunities like this, I would even argue North America wide, in which an element of Three Sisters has all of these things coming together.

And so you do see, because of that airport presence, you see international buyers. They’re like: This is an amazing place. I want to come and be here, and I can fly direct, and then drive out with my rental car, and I’m in Canmore. It’s a beautiful world, right?

Because of that airport presence, you see international buyers. They’re like: This is an amazing place.

OLLENBERGER: There are people that live and work in Calgary that end up living in Canmore and working in Calgary. And if you look at the highway in the morning and in the afternoon, there’s a lot of commuter traffic coming out of Canmore back and forth. Especially kind of the Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday range when you’ve got to be downtown again type of thing. So there are a lot of people like that, because they go home, they can pop out their door, and they’re going mountain biking right away.

I think the other element too is if you’re in Edmonton, you can’t really buy land around Jasper National Park. There are a lot of Edmontonians that say, Canmore is where we’re going to buy. Whereas there are a lot of Calgarians that say: We’re going to go to Invermere. That’s still within a reasonable driving distance.

So it’s the crux of all those factors and influences that are coming together, that people say: I think Canmore is a pretty special place.

The legacy of coal extraction

Canmore is unique for another reason, too. Parts of the town are undermined. In other words, built on top of mined-out coal seams, many of them at steep angles.

OLLENBERGER: It's not the exclusive mine territory within Canmore—much of Canmore on the south side of it has been mined before—but a lot of this property was the outcome of 1979 when the Canmore mines ended.

GERRY STEPHENSON: I've worked in over 30 countries and visited and worked in probably 300 mines in the course of my career. And I've never seen anything anywhere as complex as this. The gradients vary from flat to 90 degrees, and every angle in between.

KLASZUS: This is Gerry Stephenson. He was chief mining engineer and assistant general manager for the Canmore Mines in the ’60s and ’70s. Stephenson died in 2019, but a couple years prior, he collaborated with local filmmaker Glen Crawford on a video about undermining on the Three Sisters lands.

STEPHENSON: Up to four individual seams were mined in some areas, one above the other.

KLASZUS: If you walk near some of the oldest mines in town, near Rundleview Estates, you can still see signs warning you to stay on the path because there are old mine workings nearby. Some of the heaviest undermining is on the undeveloped Three Sisters lands, which has raised longstanding concerns about public safety and liability.

KLASZUS: After the last Canmore Mine shut down, Stephenson started his own engineering consultancy. Three Sisters Golf Resorts hired him in the 1990s to do undermining mitigation.

Some areas of Three Sisters posed little trouble, like the Peaks of Grassi and Homesteads subdivisions, where Stephenson said there wasn’t much impact from undermining. But other areas, particularly in and around the Stewart Creek subdivision, required more costly mitigation.

STEPHENSON: When you tackle a project like this, you find that you’ve got two categories of hazard to deal with. The first, of course, is the instability of the surface caused by the shallow and steep mine workings. And the second, which is equally dangerous, is the existence of old caves where the workings have come to the surface, caused it to collapse. All the shafts, all the tunnels that have come to the surface.

KLASZUS: After the NRCB approved the Three Sisters project in 1992, it recommended the creation of an undermining review committee. Raymond Haimila was on that committee, and he showed me a bunch of his old maps depicting the coal mines. He rolled them out on a big table at the library.

HAIMILA: This is the Wilson seam. That's where I worked. This is all undermined here.

KLASZUS: In the 1980s, Haimila built a house on Rundleview Drive in the subdivision developed by Peter Pocklington’s company. That area is undermined. And he recalls one day when his daughter was playing with a friend across the street, where a bunch of new houses were slated to be built.

HAIMILA: A fellow came and knocked on the door and said: You should let your children know there's a hole by the tree across the street. And I said, a hole. He said, Yeah, it's about a foot across.

So I went and got the 2 x 10 and a flashlight and I put it over this hole. It was about a foot across. And when I put the flashlight in, it was just grass. And when you look underneath the grass, the hole was about 20 feet across. And it went straight down into the old mine workings about 30 feet down. And you could see the tops of timbers from the old mine. And they ended up finding another one or two holes up there, around the same time, filled them in and put fences around two of them. And they took six or seven lots off the market.

That area was mined approximately 80 years before the collapse occurred.

KLASZUS: Those areas are still fenced off today.

KLASZUS: To show a more recent example of subsidence, Haimila drove me to the Three Sisters Parkway.

HAIMILA: You can see there's a change in pavement down here. This is where it collapsed.

KLASZUS: In the last 20 years, two undermining collapses on Three Sisters lands have affected public infrastructure. One is this roadway, which collapsed in 2004 over two old mine shafts that had been capped and backfilled. Ollenberger says a compromised water line was partly to blame.

OLLENBERGER: It took 20 years to show up. And then finally the waterline burst eroded away some material, and there was a void formed. And now there's a whole bridge deck underneath the highway in that particular location. So that won't be coming back.

KLASZUS: The second sinkhole happened at Three Sisters in 2010. A town pathway collapsed near a road called Dyrgas Gate, over the air shaft of a mine that closed around 1940. And this wasn't entirely unexpected—Stephenson and other engineers had identified the shaft in the ’90s, but had trouble pinpointing the exact location.

OLLENBERGER: And he said, You know what, I don't know exactly where it is, but it's around here somewhere. So we're going to set everything way back. And we're going to do a bunch of mitigation right here so nobody can get hurt. We're going to have a net, we're gonna have a safety catch, we have geonetting. And if it ever shows up, we'll know exactly where it is, and we'll go fix it. Which is exactly what happened.

KLASZUS: The Dyrgas Gate sinkhole set off a debate about who should pay when public infrastructure is damaged by subsidance—the province or the town. The province ultimately gave the town $600,000 for temporary remediation of the sinkhole. The Town of Canmore told me this was all the town spent on remediation. But the local paper, the Rocky Mountain Outlook, reported that the total cost was $1.7 million dollars, with the town needing to pay the difference.

In any case, undermining-related incidents are rare. It’s been fourteen years since that sinkhole appeared. But when they do happen, they can be costly. Here’s Stephenson speaking to town council in 2017 about the lessons from the Dyrgas Gate sinkhole.

STEPHENSON: After 62 years in mining, 30 years’ experience of mitigation, I knew that it’s impossible, with the best engineering practice, to guarantee a 100% safe situation. Events such as Dyrgas Gate will continue to happen. Not necessarily annually, but they will continue. So what is the lesson of all this? The taxpayer must not be left to pay such cost.

Mitigating undermined land

KLASZUS: Three Sisters makes no secret of this being undermined land. Ollenberger says Three Sisters is the most complex project of its kind in Alberta—in part, because of the undermining aspect.

OLLENBERGER: I am a geotech engineer, and I'm probably now the person that's been working the longest on undermining on Three Sisters that's still working on it. And I find it a fascinating subject. But some of the concerns that are expressed, saying, you know, all of Three Sisters is going to fall into a giant cavern suddenly without warning—that's not the case. Do we have to be cautious? Yes. Do we have to be smart? Yes. Do we have to do all the right engineering? Absolutely.

The level of rigour when you’re putting a house on top, or a piece of public infrastructure, it is significant. But we hear about it. We hear about it all the time. We hear about concerns. We hear lots of people say, boy, I talked to somebody that used to work in the mines, and they said this...

Well, I’m going to tell you, there is a big difference between somebody that’s trying to dig coal out and take it out of there, and what they’re worried about, which is a temporary safety thing—will the roof stand up long enough so I can get the coal and get out?—versus somebody that’s above the ground looking down, like a geotechnical engineer saying this needs to be stable up here.

The mining people didn’t worry about if it was all stable up here. They want it to be stable down below. We want it to be stable up above. It’s a different perspective.

Do we have to be cautious? Yes. Do we have to be smart? Yes. Do we have to do all the right engineering? Absolutely.

KLASZUS: One mitigation method that Three Sisters uses involves filling some of the old mines with paste backfill.

OLLENBERGER: It’s not so much that you need like this super strong piece of iron to be holding up the roof. It’s really a bulk material question: Is there something there? Now, I’m not saying paper mache, but something a tenth of the strength of a city sidewalk is enough.

The reality though, is that it’s been 40 years since the last mine closed, but much of the mines we’re talking about have been closed for almost a century now, in some cases. And so a lot of the movement that would occur has occurred in many of them.

Think of it like pouring a glass of marbles into a jar. There's still air, there's still gaps between the marbles, but the marbles have filled the jar and you can’t push them down anymore. That's what happens a lot when you get blocks of rock that fall into a void space. They interlink, they still have voids in between them, but they can't push down anymore.

KLASZUS: In 2020, the UCP introduced revised undermining legislation specifically for Canmore.

OLLENBERGER: So there is a process that's actually unique to Three Sisters on undermining that doesn't exist anywhere else in the province. It has its own regulation in terms of what you must do and the steps you must take and an independent third party review.

KLASZUS: Under the law, developers need liability insurance of at least $5 million for two years after they’re involved with the property. The same law requires that engineers have insurance for 10 years after they certify undermined projects. Those are the longest timelines possible under Alberta’s Limitations Act, but Haimila believes they’re not long enough.

HAIMILA: These things occur over decades and hundreds of years, not two years and 10 years. And I think the town is going to end up paying dearly for not having a surety bond of some sort in the millions of dollars, or the liability increased to 50 years, to 100 years.

KLASZUS: Even if the liability timeframe was increased, the developer or engineering company may or may not be around that long. This project has already seen two bankruptcies over the years. Here’s what Gerry Stephenson suggested to town council in 2017.

STEPHENSON: Insurance is not the answer... A trust fund should be administered by the provincial government [with] payments being made by the developer into the fund based on the development value on undermined land. The fund would then be used to pay for events such as Dyrgas Gate.

KLASZUS: It remains murky who would pay for future damage from undermining.

HAIMILA: Two years’ and ten years’ liability insurance is nothing. Those people get off—they build their complexes, they build their subdivisions. Ten years later, they have all their money and they're gone.

A trust fund should be administered by the provincial government [with] payments being made by the developer into the fund.

OLLENBERGER: Will somebody be on the hook for 100 years? Well, the answer is no, right? Nobody’s on the hook for 100 years, because even the lifespan of a structure is like 50 to 60. So it depends on the situation. It depends on what the structure was. It depends on the work that was done. I don’t think there’s one answer in terms of who can we go to and say: It’s going to be your fault. There is no it’s-going-to-be-your-fault-no-matter-what person; that doesn’t exist.

So I think the answer that you said, whereas it may be a combination of public/private and insurance companies, is probably the most correct one.

The next episode...

KLASZUS: If you go just west of the Three Sisters Creek subdivision, which is in the middle of the project lands that run along the Bow Valley, you’ll see an unfinished golf course. And there’s a reason there’s nothing built there.

KRISTY DAVISON: They got a segment of their plan approved contingent on the fact that they would not develop on one of those golf courses. That only golf courses can be done on that land because it's severely undermined and because it butts up to the wildlife corridor. It's a buffer zone to the wildlife corridor. Animals can still use the golf course.

KLASZUS: For years, that was the plan. After all, the company that got provincial approval was called Three Sisters Golf Resorts. But as we’ll hear in the next episode, that was then. The developer now has a different plan—one that has become a flashpoint in the struggle over Canmore’s future.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl. He can be reached at hello@sprawlcalgary.com. The next episode in this series will come out later in February. Support The Sprawl's independent journalism today!

Support independent Calgary journalism that digs deep.

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl is committed to in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism—but we can only keep doing stories like this one with community support. Join us by becoming a Sprawl member today!