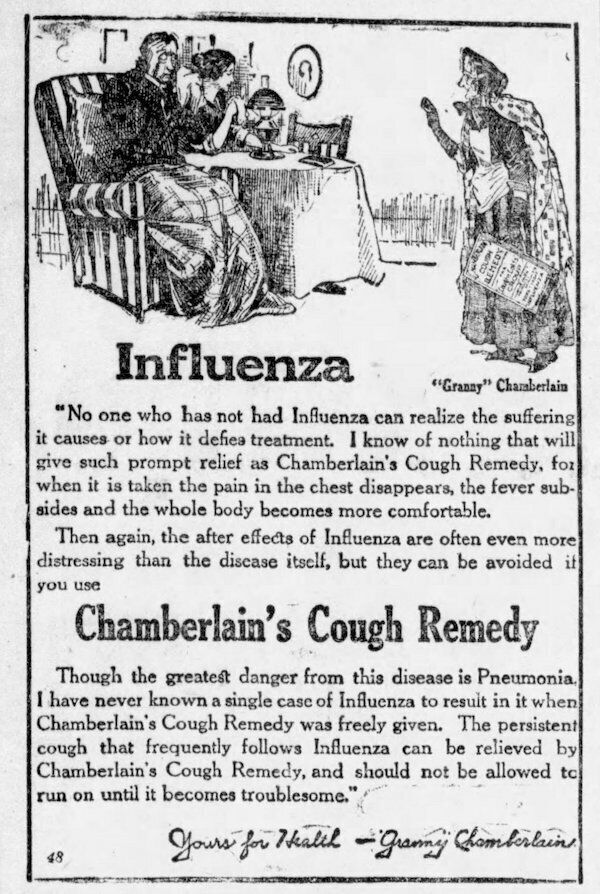

"Granny Chamberlain" in flu remedy ad, 1919.

In the midst of this coronavirus clampdown, every day that our lives are disrupted makes the situation feel more unprecedented.

In many ways, it is—not least because most of us have never lived through a public health crisis of this magnitude or duration.

But of course this is not the first pandemic to sweep the globe, nor is it the first time Albertans have had to grapple with a deadly contagious disease.

In fact, it was in part due to successive epidemics of smallpox that Alberta as we know it exists at all: If not for the horrific death toll among Indigenous communities—two-thirds of the Blackfoot died in 1838 alone—the history of early colonial western Canada might have been quite different.

But in seeking a comparison for the widespread disruption to social and economic life we are currently living through, the closest parallel is the influenza pandemic of 1918.

Like smallpox, the scale of devastation is hard to imagine—anywhere between 17 million and 100 million people died, or between 1 and 6 per cent of the global population, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in recorded history.

The mass movement of people in the First World War enabled the virus to rapidly go global in an era before jet travel. The immense death toll of the war, along with widespread devastation to societies and economies, made the unexpected blow of a pandemic all the more terrible.

Canada suffered 67,000 deaths in the war; the flu would claim another 50,000, including 4,000 Albertans.

Face masks and theatre closures

Though 1918 is a world apart from 2020 in countless ways, there is a surprising number of parallels between how we responded then and now.

We’re under public health orders that impose restrictions on our normal lives for the good of public health, and it was no different a century ago. In December 1918, the Board of Health of Calgary printed in the Calgary Herald a lengthy list of regulations.

Children were forbidden from entering stores employing over 30 people. Shopkeepers had to post signs that said: "No child under 15 years of age allowed in this store."

The restrictions also prohibited Sunday school, mandated the closure of theatres and cabarets except for a handful of hours, and required masks be worn by healthcare workers, barbers, dentists, bakers and cooks.

All students in secondary or post-secondary schools were to be “inspected as soon as can be in the morning and again in the afternoon.”

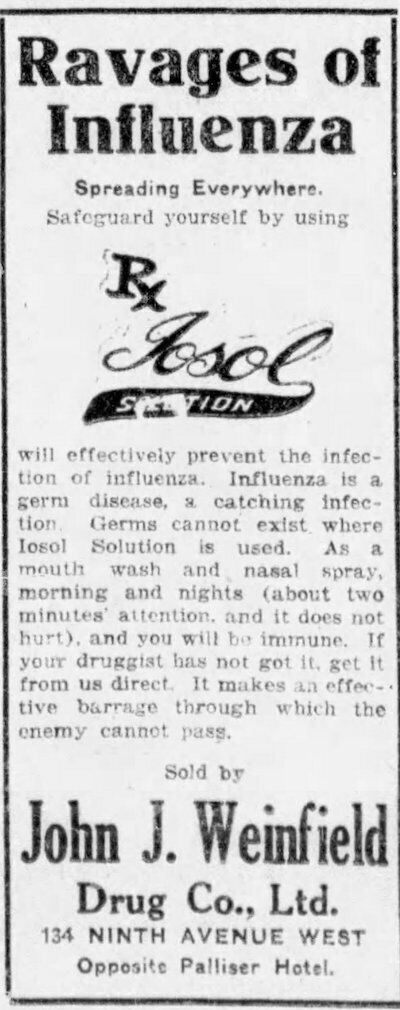

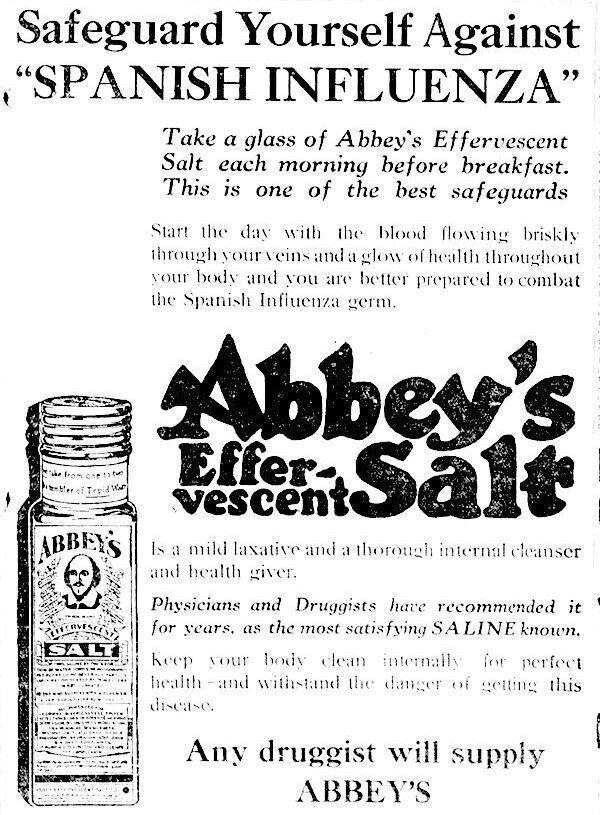

False treatments back then didn’t come with presidential endorsements, but they did appear regularly in newspapers. The Herald had ads nearly every day promoting “positive” cures with testimonials: “safe,” “recommended,” laxative quinine tablets, effervescent salts, mouthwash and nasal sprays that can make you “immune.”

Chamberlain’s Cough Remedy even claimed that it had never failed to prevent influenza from progressing to pneumonia.

Dubious cures were even reported as straight news. “Real cure for influenza is made public,” blared a headline in the June 18, 1919 Herald. The story—which was surprisingly brief given the apparent significance of the news—presented the claim of a New York doctor as an unchallenged fact.

An article the following day featured a Calgary doctor explaining why the claim was nonsense.

The economy was also a concern during the 1918 pandemic, all the more so coming out of the war. One ad in the Edmonton Journal advertising a sale at Martin’s Store sounded desperate in acknowledging fear of shopping during the epidemic.

“I beg to notify you people that I have eleven windows and a back and front door that allows good fresh air into the store," said the ad. "Also the store is fumigated every night, thereby clearing the store of any infection that may be brought in.”

False treatments back then didn’t come with presidential endorsements.

Remote city council meetings, pre-Zoom

Remarkably, even tele-working was around in 1918.

The Herald reported on October 29, 1918, that Calgary’s public health officer “did not think it wise for the city fathers to get together,” forcing the cancellation of a council meeting.

Instead, “the city clerk called the various aldermen up on the telephone and asked them their opinion with reference to one or two matters that the mayor and commissioners thought should be settled at once.”

Not exactly a Zoom call, but no privacy issues either.

Of course, telephone networks back then relied on physical switchboards operated by actual people, typically women, who put themselves at risk along with other essential workers to keep the phone lines open.

Alberta Government Telephones (AGT), the publicly-owned phone company, placed a notice in the Nov. 7, 1918, issue of the Albertan in which general superintendent W. R. Pearce praised the operators.

“They are doing heroic work, quietly, unostentatiously... In some of the more affected towns where nurses are unobtainable the telephone girls have volunteered their services to assist in the isolation hospitals.”

Those who are keeping the Internet working are providing an essential service during #Covid19. They are analogous to the telephone operators during the #SpanishFlu pandemic in 1918–19. This ad in the Albertan (now @calgarysun) is from Nov. 7, 1918. AGT was a @TELUS forerunner. pic.twitter.com/LhrsQSLmMe

— Harry Sanders (@harry_historian) April 7, 2020

In 1918, no one expected immediate solutions

Not everything about the two pandemics is the same, of course.

“We now have expectations of solutions to medical problems that would have seemed absurd to people not all that long ago,” said Dr. Janice Dickin, professor emerita at the University of Calgary, who has written extensively on the 1918 pandemic since the 1970s.

Her work includes an essay in the 2004 anthology Harm’s Way, about disasters in western Canada.

In 1918, you would have had no refrigerator, perhaps no telephone, no news except newspapers and word of mouth, and unless you lived in a city, you were likely a long way from healthcare, especially if you didn’t have an automobile.

(So-called ’Spanish’ flu was named because newspapers in neutral Spain published stories about the pandemic while countries at war suppressed the news, which says a lot about the reliability and speed of information at the time.)

Forget hoarding toilet paper, says Dickin—it was too expensive, and you probably would have just used the pages of the Eaton’s catalogue.

One of the things that 1918 has over 2020, Dickin points out is that people had to look after each other, neighbours left food for families who had quarantine notices placarded on their premises.

“Now we just have to avoid them!” she said.

Technology, though, gives us new ways to do the same things. For example, a new app developed in Calgary, Neighbours in Need, helps connect people who want to help those who need assistance during this period of social distancing—everything from errands and grocery runs to just a phone call to break up the loneliness.

Living through similar fear, uncertainty, and chaos, we respond now much as we did then: By finding ways to pull together and support one another.

Perhaps that, most of all, is the lesson to take from our history.

Taylor Lambert is a Calgary writer and the author of Darwin's Moving, which won the 2018 City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize.

Now more than ever, we need strong independent journalism in Alberta. That's what The Sprawl is here for! When you become a Sprawl member, it means our writers, cartoonists and photographers can do more of the journalism we need right now. Become a Sprawl member today!

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!