So long, 16th Avenue shop

Calgary is lesser without it.

The diminutive wood-frame building, with its stuccoed false front and distinctive sign, was a landmark for thousands of daily motorists on this stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway.

Few, if any, ever set foot inside the 110-year-old building at 120 16th Avenue N.W.

It didn’t matter. Just the sight of it added richness to the commute and city tapestry. Few structures are as old and evocative of what the street had once been.

When the building was constructed in 1909 or 1910, this stretch of 16th Avenue lay in the short-lived village of Crescent Heights, which had its own council, school board, constable and volunteer fire brigade.

Its demolition in September severed one of the last tangible links to that forgotten history.

Some Calgarians had more than a passing acquaintance with the building.

Al Gough, who operated his store and repair shop there for over a quarter-century, maintained instruments for most of the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra’s violinists. Loyal customers trusted him to repair their instruments or to sell them new ones. And the small scholarships he gave to young competitors in the Kiwanis Music Festival remain in their memories.

Gough built his first instrument at the age of six, but he made his initial career as a mechanic. In the 1980s, he apprenticed as a luthier (a maker of stringed instruments) and established his niche business.

Gough maintained instruments for most of the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra’s violinists.

It was shuttered in 2013 when Gough died. “The little building has sat vacant before,” observed local historian Alan Zakrison earlier this year, “always waiting for another little business to make it come alive.”

Indeed, every generation had its Al Gough at 120 16th Avenue N.W.

The first might have been H. Beale, its earliest recorded owner. But little is known of him, and nothing is known of the building’s original use.

Next came Milward V. Anderson, a plumber from Edinburgh who rented it for his business in 1912. Anderson lived in Crescent Heights and was financial secretary of the neighbourhood’s Foresters lodge. He once told the Calgary Herald that the city should have been on the North Hill and not “in the swamps below.”

Anderson Plumbing soon moved to another 16th Avenue location, and the little building remained vacant for years. Its mostly short-term occupants in the 1920s and 1930s included Margaret Knox’s hat shop, Gertrude Lowe’s dry goods store, and Alma Campbell’s confectionery.

From about 1941 to 1955, it doubled as Nat’s Barber Shop and the home of owner Ignatz (“Nat”) Marbach, his wife, Ivy, and their children.

Nat and Ivy built a rear extension in the early '40s.

Nat saved customers’ hair to insulate the garage. “It took him almost a year in his one-chair barber shop to get enough,” the Herald reported in 1942, “but the job is now finished and Nat says it’s fine stuff.”

Nat decorated his workplace with 200 types of fishing lures that he made from customers’ hair and bright pieces of metal supplied by friends who worked in machine shops.

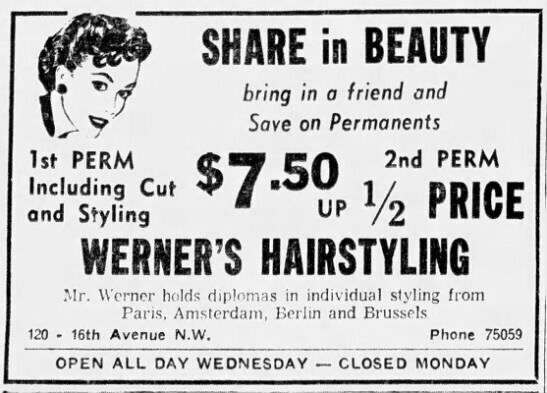

Dutch immigrant Werner Bastiaannet, a trained beautician and an accomplished zither player, took over in 1955 and operated Werner’s Hairstyling and Barber Shop with his wife, Paula.

In 1957, Werner performed with the CPO at the new Jubilee Auditorium using an electric zither that he had personally modified.

Frits Bastiaannet, who lived behind the shop with his parents and siblings, remembers his father performing at the Banff Springs Hotel for Prince Rainier of Monaco. “He asked my mother to dance,” Frits recalled.

In 1961, Arlo Musselman bought the business for $4,200 and operated it with his wife, Edith. Their son Shane was born in the family quarters behind the salon, and he had his first haircut in the shop’s barber chair—which now has pride of place in his Scenic Acres living room.

Arlo’s Hairstyling & Barber Shop moved in the mid-1970s, and the building became the home of Henry T. Kwong, a Hong Kong immigrant who co-founded the nearby Gold Horse Restaurant in 1976.

Finally, in 1986, Al Gough hung his shingle.

Two decades later, a street-widening project threatened his tenancy. Alone on the block, Gough’s shop occupied its entire lot, and public consultations identified this spot as a “pinch point” that made pedestrians feel unsafe, even without a wider 16th Avenue. The city bought the building to demolish it.

But ultimately, the city left Gough alone. “He has put up with enough,” said a transportation spokesperson in 2010.

The city subdivided the property, kept the part it needed for the sidewalk and sold the remaining portion of the lot. Gough’s empty shop outlived him.

While it was under threat, customer Mary Graham vented her frustration in a letter to the Herald.

“What is the city going to do,” she asked, “when someone in a public consultation points out that we’ve lost our soul by eliminating places like this violin shop that give us significance?”

Graham answered her own question: “Remove the sterile concrete pedestrian corridor and try to get it back.”

If only we could.

Harry Sanders is a Calgary historian and freelance writer.

The Sprawl is crowdfunded, ad-free and made in Calgary. Become a Sprawl member today to support independent local journalism!

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!