Sprawlcast: The Longest Playground Zone in Calgary

A history of city speed limits.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!

Sprawlcast is a collaboration between CJSW 90.9 FM and The Sprawl. It's a show for curious Albertans who want more than the daily news grind. A transcript of this episode is below. (UPDATE: On February 1, city council voted to lower residential speed limits. This transcript has been updated to reflect this.)

WENDY BROWNIE: I'm just actually saddened to think that it has taken 31 years and not a lot has been done.

JEREMY KLASZUS (HOST): It’s an issue that Calgary city council has been grappling with for decades. Actually, it goes back even further than that. City council has been asking “what should we do about this?” for over a century, and that’s no exaggeration. I’m talking about the issue of human injuries and deaths inflicted by cars on city streets—and how to slow drivers down.

About a quarter of traffic collisions in Calgary happen in residential neighbourhoods, according to the city. That shakes out to just over 9,000 collisions a year. And of those, more than 500 cause serious injury or death.

Now, city hall has revisited this issue many times, looking at the pros and cons of reducing speed limits in neighbourhoods. And on February 1, city council finally took action.

Women have often been leading the charge on this issue and organizing for change.

The change is actually quite tame. It’s what city admin calls an “incremental” approach.

The research shows that 30 k.p.h. is best if you really want to save lives and minimize injuries. But the Calgary plan is to reduce most (but not all) residential speed limits from 50 to 40 k.p.h.—with the idea of eventually going to 30. In the meantime, city admin is recommending that streets are built and retrofitted so that the 30 speed limit, if it ever comes into effect, will be “credible” for drivers.

But let’s zoom out—because if you go back over a century in Calgary, city council was discussing this very same thing. And if you look at the history, it’s been women who have often been leading the charge on this issue and organizing for change.

A century-old campaign to lower speed limits

In 1917, the Calgary Herald noted that “the increasing number of automobile accidents in Calgary is becoming a serious matter.” Cars were still new and as they began to overtake city streets, they were threatening the safety of the walking and bicycling public. The big problem was street corners. Drivers were taking corners at speed and hitting people.

Now, at the time, Calgary had a provincially-mandated speed limit of 20 miles per hour, or 32 k.p.h. The speed limit for corners was 10 m.p.h. and the Herald wanted to see that reduced to five m.p.h. or less.

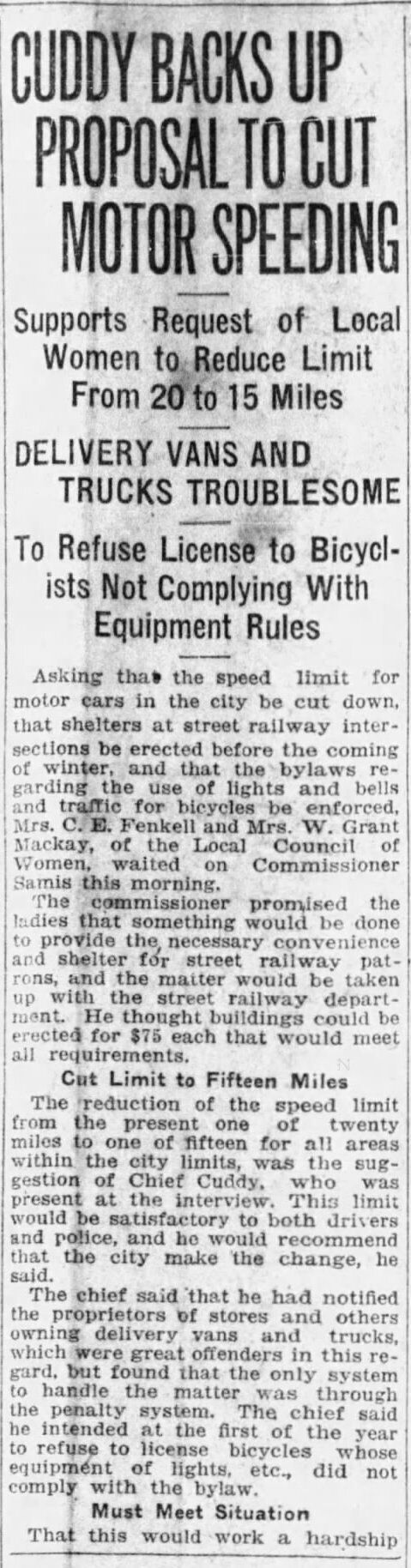

As time went on, there were more cars on the streets and more collisions. And in 1918, there was talk of reducing the speed limit from 20 to 15 m.p.h. The Local Council of Women called for this, and the police chief of the day, Alfred Cuddy, supported the change.

KLASZUS: But drivers and industry rose up in protest. And the arguments for and against are very familiar. One driver told the Herald that “police are starting at the wrong end of the trouble when they begin by reducing the speed limit.”

KLASZUS: Well, the Automobile Trades Association registered its objection and the campaign for lower speed limits was kiboshed shortly after. One alderman argued that the existing rules were good ones. The issue, he said, was that they weren’t being enforced.

And so years passed and eventually, instead of the speed limit going down, it went up. In 1953 city council increased the speed limit to 30 m.p.h., which shakes out to just under 50 k.p.h. And almost immediately, people asked why. One Herald subscriber wrote a letter to the editor in 1955 and suggested that it should be 20 m.p.h. in residential areas. The fact that this wasn’t in place, they wrote, showed “base negligence by city council as a whole.”

Time passed and over the years we got playground zones and school zones and photo radar to try and reduce injuries and deaths.

But even the complaints of photo radar aren’t new.

KLASZUS: In 1927, the Herald complained about police camping out on city highways to catch speeders, including one stretch by Mewata Park west of downtown. The Herald noted that there were several such strips of roadway in the city. If the goal is safety, they asked, why are police camping out where there are no intersections or blind corners? What was the real motivation? “Every so often,” wrote the Herald, “one gets the idea that their interpretation of the regulation is entirely mercenary.”

Or to translate that into modern terms: it’s a cash cow.

Now let’s fast forward nearly a century to 2019.

'I have never seen a more ridiculous 30 zone'

ANDREW BECKLER: Earlier this week, the CBC released a report on the use of photo radar in playground zones in our city. Now, I've made no secret over the years about my disdain for photo radar and how I think it's mostly about generating revenue and has very little to do with public safety.

KLASZUS: That was Andrew Beckler, one of the morning hosts on X92.9. And he was responding to a CBC Calgary investigation into where photo radar is deployed in the city.

BECKLER: As it turns out, of the 1,200 playground zones in the city, nearly two thirds of tickets in the last three years were issued in just 10 of them. That's absolutely crazy. It's not that people are speeding that much more often in these locations, or that pedestrian safety is that much more important in these locations. It's that the city has realized that these spots are making enormous money for them, so they're parking photo radar there every chance they get.

Now, before I even looked at the report, I knew what the number one location would be, because I complained about it almost immediately when I moved here four years ago.

I have never seen a more ridiculous 30 zone than on Elbow Drive. Over 600 meters of reduced speed for what's essentially two swings and a slide, which are behind a fence. There's no school nearby. The footpath is set back from the road. It feels absurd to drive 30 through this thing. Why is this one of the longest playground zones in Canada? Is it because these are all million-dollar properties?

Why is this one of the longest playground zones in Canada? Is it because these are all million-dollar properties?

KLASZUS: The Elbow Drive playground zone is a contentious one. And CBC’s investigation shone a light on inequality when it comes to speed limits and enforcement. They found that of the 10 top zones, where the bulk of photo radar tickets were issued between 2016 and 2018, none were east of Deerfoot Trail.

COUNCILLOR GEORGE CHAHAL: I mean, that’s concerning.

KLASZUS: This is Councillor George Chahal, who represents Ward 5 in the city’s northeast.

CHAHAL: And when we talk about the inequalities, or equity, when it comes to having safe neighborhoods and communities, there's a clear issue there.

We’ve had a public outcry in many communities, from Falconridge to Saddle Ridge to Skyview Ranch and Redstone, asking for more enforcement.

CHAHAL: And I can point to you 10 locations, easily, in Ward 5 or in northeast Calgary that could use a significant amount of enforcement. There's regular speeding; there's been accidents involving pedestrians. Even over the last number of months, we've seen that occur.

And we've had a public outcry in many communities, from Falconridge to Saddle Ridge to Skyview Ranch and Redstone, asking for more enforcement to deal with the excessive speeding that's occurring in our communities.

KLASZUS: When CBC did its investigation, looking at 2016 to 2018, they found that police parked a photo radar van on Elbow Drive more days than they didn’t—a full 78% of the time. Police collected more than $5-million in fines there over those three years.

This is something I’ve wondered about for a long time. What’s the story behind that Elbow Drive playground zone? Why is it so long? And how did it come to be?

To find answers, we need to go back to 1990.

Hello Calgary

In 1990, Calgary was a city of 700,000 people. The city was still riding the high from the Winter Olympics two years prior. And oil and gas was very much the dominant industry, employing a good portion of the population. People like Bruce Gordon.

BRUCE GORDON: I was working in the oil business for a company called Bow Valley Industries and managed their land department.

KLASZUS: Bruce had just gotten married.

JAN GORDON: We'd both been divorced. We'd only been married for a year and a half.

KLASZUS: Jan Gordon is a marriage and family therapist and an instructor at St Mary’s University, but at the time she was just launching her career. Bruce and Jan each had two kids when they married. The youngest was Ian, and in 1990, he was seven years old. The Gordons lived in the community of Mayfair, just south of Glenmore Trail, but Ian attended Rideau Park School across the river from Elbow Drive. And after school he’d often walk to the Glencoe Club, which is a private sports club.

He always told everybody that he was going to be a paleontologist. That was his aim in life.

JAN: Ian was bright, funny. Stubborn little cuss. I grew up in a family where—I'm the eldest of six kids, and the family belief was, keep your kids busy. And given that I had been a member of the Glencoe for many years, it just seemed natural to keep the kids in the Glencoe as well, bring Bruce and his boys into the Glencoe, so we had Ian in badminton lessons. He was a good little athlete. He liked to play baseball and soccer. And very loquacious. Lots to say about lots of things.

BRUCE: Very inventive, too. He and his buddy Oliver had invented a game. It was like a detective game, board game. And it was quite complicated for a couple of seven-year-olds…. But he always told everybody that he was going to be a paleontologist. That was his aim in life, to be a paleontologist.

KLASZUS: It was late September. And Ian had just started Grade 3. On the afternoon of September 26, Jan was heading to a meeting and she noticed something unusual.

JAN: I was on my way driving north… on Elbow Drive to go to Rideau Park School to have a conversation with the teachers about him being transferred into the GATE program. That's the Gifted and Talented Education Program. And the traffic was really backed up. I was at the lights at about Sifton Boulevard when it really slowed down, and I thought, this is a little early in the day for this kind of heavy traffic. And as I kept on driving slowly—the ambulance was gone by this time, but his backpack had been cut off him and it was lying on the side of the road.

KLASZUS: She recognized it immediately. It was a special backpack that Ian’s uncle had given him. And right away, Jan went to the Glencoe.

JAN: …and looked around and looked around and asked people, and one of his classmates came up to me and said that Ian had been hit. And again, we're back before cell phones. So the Glencoe actually phoned Bruce.

The ambulance was gone by this time, but his backpack had been cut off him and it was lying on the side of the road.

BRUCE: And I was in a meeting at work. I was a manager of a number of departments at the company I worked at, and they called me out of the meeting and said, "There's a phone call for you." And they told me that he had been hit and was on his way to the Children's Hospital—the old Children's Hospital at the top of 17th Avenue by Crowchild.

And I just remember dropping the phone and heading out the door. I didn't even say anything to the people in the meeting or anything. I just headed out the door, got in the car, drove up to the Children's Hospital and jumped out of the car and went running into the hospital looking for somebody to talk to. "Where is he, and what's going on?"

And they actually had a person there whose job it is to meet distraught parents coming flying through the door when their children have been hurt. Mary, her name was. And she stopped me and started talking to me and trying to calm me down, which was beginning to work until I saw him go by on a stretcher.

We had no idea for over 72 hours whether he was going to live or not.

BRUCE: And his whole face was purple and – you know, just … So I started getting upset again, and they put me in a room and gave me a cup of coffee and said, "Stay here. Don't go. We'll talk to you when we have time." And said, you know, the main thing is get him into the trauma unit in the ICU.

JAN: And then I came in.

BRUCE: And then she showed up.

JAN: So I was a few minutes behind him getting to the hospital.

BRUCE: And came in and calmed me down some more. But it was—well, it was terrifying. And we had no idea for over 72 hours whether he was going to live or not.

The consequences of crossing the street after school

KLASZUS: Over time, the Gordons figured out what had happened to Ian when he tried to cross Elbow Drive after school that day.

BRUCE: When the accident happened, Ian was crossing. He came across the little swinging bridge, and he was with a bunch of other kids from Rideau Park School, and most of them were headed across either to go home or go over to the Glencoe Club, which is about three blocks from there.

What had happened is he had pushed the button and walked out to start onto the street. There was a car already stopped at the crosswalk, and the fellow in the truck that hit him came up and went around in the inside lane and hit him and knocked him off into the curb, giving him his traumatic brain injury. And he's still right-side hemiplegic. He's paralyzed on his right side, partially paralyzed.

Fortunately, they had had… I don't remember what the generic name for it is, but it's curare—in the ambulance, and it was administered right away. One of the problems with brain injuries is that sometimes they'll convulse, and it just makes it worse because they're snapping around. They're unconscious, but they're snapping around and their brain is splashing around, and their body, so they'd given him this derivative of—

JAN: It was called Pavulon.

BRUCE: Pavulon, that's it. And it just basically semi-paralyzes them so that they don't thrash around. And it probably saved him from further damage, because he'd been hit in the side of the head by the truck, flown through the air, and then landed on the back of his head, so you got the bowl of jelly thing happening with the brain. So he wasn't just—just the right side. There were other things that went wrong as well, and other parts of his body that didn't work properly as well.

There was a car already stopped at the crosswalk, and the fellow in the truck that hit him came up and went around in the inside lane.

BRUCE: And that brilliant little mind that was in there, one of the neuropsychologists said, "Well, it was probably a Ferrari engine in there, and now it's a Volkswagen. It'll still get you where you want to go, but you're not going to go there very fast."

And that's more or less what's happened to him. I mean, he has a university degree. It took him 10 years to get it, and a lot of help, but he got it. But he's not competitively employable, because he can't focus on things long enough...

He's estranged from us, by the way. Once he got finished with university, he moved to Edmonton to follow some friends of his, and he still lives up there on his own. But he doesn't communicate with us.

A family's lives turned upside down

KLASZUS: After the incident in 1990, the Gordons’ lives were turned upside down. Jan was offered a job she wanted and had to turn it down to take care of Ian. And Ian had to learn to walk and talk again. He found his way back into sports, playing with the Townsend Tigers.

BRUCE: That's a wheelchair hockey team that is at the Townsend School, and every year they have a match with the Flames. Ever since the Flames got here 40 years ago, they've had a match with the Flames, which the Townsend Tigers have a 40 and 0 record on. They have beaten the Flames every single time because the Flames have to get in a wheelchair too. And not just any wheelchair. They have to get into a kids' wheelchair. And some of these kids are quick in those wheelchairs.

But it's also—I mean, Harvey the Hound shows up, and he does things like pulling the goalpost away and putting it back so that the Flames can't score and… it's a lot of fun. It's a great thing that they do every year, and they get their pictures taken and have their own jerseys, the Townsend Tigers jerseys.

KLASZUS: So he was into that.

BRUCE: Oh, yeah. That was fun for him. But then he didn't want to be in it anymore because he had to be in a wheelchair in order to play. He wanted to do sports where he could…

KLASZUS: So was he in a wheelchair when he came home?

BRUCE: He was on a walker. At that point he was on a walker. Yeah, his right leg was—the hemiplegia, it was fairly—in his right side, where he's semi-paralyzed. His left leg had been broken. His ankle was broken by the incident because, when he got hit in the side of the head here, he also got hit here and had been pinned together and all that sort of thing. And I think his left arm was broken as well, and he had a fractured skull. He still, to this day, has double vision. He's had a couple of eye surgeries, but he can't—

JAN: And he has hearing deficits.

BRUCE: —so he can't drive.

JAN: He's got a hearing deficit as well from where he was hit, and the vision was poor. I mean, his eyeball was almost—

BRUCE: Yeah, it was almost out.

JAN: —resting on his cheek.

BRUCE: Oh, yeah. I told you, when I saw him go by in the hospital, his face was purple, but, like, his eye was out on his cheek.

JAN: It was. And blood coming from his ear. He was pretty damaged.

That same week, drivers hit two more pedestrians

KLASZUS: The same week that Ian got hit in the fall of 1990, drivers hit two other pedestrians on Elbow Drive. Ian had been struck on a Wednesday, and on Friday morning, as Ian lay in critical condition, a driver hit a senior who was crossing the street. The collision broke her hip. This was further south on 49th Avenue.

The community called on city hall and police to do something to slow down traffic, but after the first two accidents, a police traffic inspector told the Herald that Elbow Drive was no more of a problem than other city roadways with similar volumes of traffic. “We’ve got a whole city to look after,” he said, “not just Elbow Park.”

But then, the following Tuesday, another driver hit a 14-year-old kid on a skateboard, resulting in a leg injury. This was at 36the Avenue, a few blocks south of where Ian was hit.

By then, residents were fed up. And they decided to do something about it.

WENDY BROWNIE: And we were a small community. We were fierce. And it was mainly a group of women who organized, and we got a lot of attention.

KLASZUS: This is Wendy Brownie. She owns Inspirati, a fine linens shop in Mission. And at the time she was president of the Elbow Park community association. And before all these pedestrians got hit, people in the neighbourhood had already been warning that someone was going to get hurt due to the heavy traffic. Elbow Drive was a kind of thoroughfare into downtown from neighbourhoods to the south.

We were a small community. We were fierce. And it was mainly a group of women who organized.

BROWNIE: I was there as community president and received all three phone calls about three accidents in one week. I knew that this was very serious, and I shared it with the other board members of our community association, and we decided that there were other communities who were experiencing the same thing—the communities that bordered along Elbow Drive.

And so we got together with these communities so that our city politicians could see that it wasn't just a singular concern.

KLASZUS: At first, the group didn’t get much response from city hall.

BROWNIE: No one called us back, and I just became a pest, because I knew that we needed accountability and we needed to be able to trust our elected officials to help us.

And we referred to the sanctity and the integrity of our community, being an inner-city community that was really the gateway into the heart of the city. We were always so proud and, I believe, continue to be proud that it's an excellent entrance from an older neighbourhood into the larger downtown area. We wanted to preserve that, but we wanted to make sure that those traveling north and south along Elbow Drive respected the fact that they were driving through a neighbourhood.

We got together with these communities so that our city politicians could see that it wasn’t just a singular concern.

KLASZUS: A week after all these pedestrians got hit in the fall of 1990, residents took to the streets with placards saying things like SAFETY #1. The city transportation department suggested random speed traps and more traffic safety education for kids in the area. This wasn’t good enough for Wendy Brownie and her group. In November of 1990, she told the Herald that “if they don’t impede the flow of traffic, we will.”

BROWNIE: We had senior citizens; we had mothers with babies in strollers; and we were organized. We knew that we had to slow down and stop traffic to get the attention of our elected officials.

KLASZUS: And the group knew what they wanted.

BROWNIE: Our end goal was to lower the traffic speed and to extend the length of the playground zone so that all communities who were affected in the accidents would be heard from.

City council agrees to expand playground zone

KLASZUS: By January of 1991, city council had agreed to expand the playground zone, lower the speed limit and install more traffic lights along Elbow Drive. And what happened next was interesting. Other communities saw this and were like—hey, we want traffic slowed down in our neighbourhood too.

BROWNIE: Following this, we were asked to come and speak to other communities to help them organize to get the attention of city hall so that, as a city, we could look at the possibility of lowering speed limits all across Calgary.

KLASZUS: In the ‘80s and ‘90s, city hall basically treated speed limit reductions as one-offs, looking at them on a case by case basis as neighbourhoods demanded it. In 1992, for example, city council reduced the speed limit on Riverdale Avenue in Elboya and Brittania in the southwest. They dropped it from 50 to 40 k.p.h. because the community clamoured for it.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, city hall basically treated speed limit reductions as one-offs.

KLASZUS: At the same time, a council committee recommended that admin look into reducing the speed limit citywide on all residential streets in Calgary. But when this came to council, councillors backed off from even doing that. That was in 1992.

'A city of haves and have-nots'

So let’s get back to the issue raised earlier in this episode—about disparity between Calgary neighbourhoods when it comes to traffic safety. Drivers hit and injure and kill kids all throughout the city. Did the Elbow Drive playground zone come about because it’s an affluent neighbourhood? That question has been raised for years and it’s a bit of a sore point among the folks who lived through it.

Wendy Brownie takes umbrage at the suggestion that the playground zone was expanded because it’s a wealthy area.

BROWNIE: It has never had anything to do with affluence. It has to do with the fact that, many years ago, we experienced three accidents in less than one week. Serious accidents. No one took charge, so we, as the people, organized. We spent, actually, years to help other communities and to make sure that people also knew that it had nothing to do with affluence. But if we can organize and share information to help, I think that was the goal then, and it certainly is the goal for today.

It has never had anything to do with affluence.

KLASZUS: When I spoke with Councillor George Chahal, he made the point that not everyone is able to put a lot of time and energy into organizing.

CHAHAL: The reality is residents of northeast Calgary are working-class Calgarians. Many of them are working two jobs to provide for their families, and they don't have the available time to organize and try to find ways to raise money to fund these type of initiatives. And so that's a city of haves and have-nots, and some who are able to and have the time and money, and others who don't.

That's the role and responsibility from city administration and elected officials, as well as law enforcement—to be able to advocate and bring forward equitable solutions to make sure all our communities are safe. And you should not have fear in any community in the city of Calgary of feeling unsafe, and public safety is a right for all Calgarians.

KLASZUS: On that last point, Wendy Brownie and Councillor Chahal are in agreement.

You should not have fear in any community in the city of Calgary of feeling unsafe.

'We cram too much in, and then we hurry'

KLASZUS: Now, interestingly, when I spoke with Bruce and Jan Gordon, they each had different opinions on whether or not city council should lower speed limits citywide.

BRUCE: If they did it the same way they did with the playground zones and said, "From 7:30 in the morning till 9:30 at night, you have to go 40 in a residential area," I would be on side with that, because that's the time of the day that you're going to have something happen and somebody's going to run out from behind a parked car or whatever.

But just to say, "No, that's it. Every district in the city, you've got to go 40," and then with the intention of taking it down to 30 later, that's just going to create nothing but a pile of speed traps. People are not going to crawl around town at 30 kilometers an hour. But, you know, from my perspective. Now, Jan has a different viewpoint on it.

JAN: Do I?

BRUCE: Well, you told me that you thought it would be just fine.

JAN: To slow it down?

BRUCE: Mm-hmm.

JAN: I do.

Just slow down, smell the roses, and leave a kid alive.

JAN: I think people are in a big hurry. They're—I don't know whether it's just because we try to do too much, we cram too much in, and then we hurry between stops. But just slow down, smell the roses, and leave a kid alive.

KLASZUS: Here’s what Wendy Brownie had to say about it.

BROWNIE: For politicians to say or to suggest that it isn't the right timing, I would ask them: Why? What is your rationale? And if you represent these communities—and I know there are communities in the northeast and the southeast who experienced the same as what we experienced many years ago—it's a simple solution. Lower the speed. Lowering the speed from 50 to 40 does make a difference.

If we had been told 31 years ago that we would have to have a plebiscite, we’d still be waiting today.

BROWNIE: And even when the speed is lowered to 40, you will still have individuals driving 70. But lowering it to 40 is not going to impede your travel time by more than, I would say, 30 seconds. But in that 30 seconds, as we experienced many years ago, a little boy was hit by a truck speeding through our playground zone, and that little boy was injured seriously.

And I don't believe that we have to have a plebiscite. If we had been told 31 years ago that we would have to have a plebiscite, we'd still be waiting today.

KLASZUS: I’m going to give the last word here to Jan Gordon.

JAN: I will say something else, if I may… You were asking how we managed. The other three kids were really traumatized as well.

BRUCE: Yes. Some more than others.

JAN: Very, very much so. My daughter, who was the oldest one at the time, this time, it almost froze her. It almost paralyzed her. And she dropped out of university. Alex became withdrawn, and—

BRUCE: Acting out. Had to go live with his mother out at the coast.

JAN: Yeah, he did some acting out. And the older boy resorted to abusing alcohol. So everybody was trying to cope with something that should never have happened. It wasn't of their doing.

So I offer you that. Every one of us were hurt.

Jeremy Klaszus is the editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

Did you appreciate this story? Become a Sprawl member today!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!