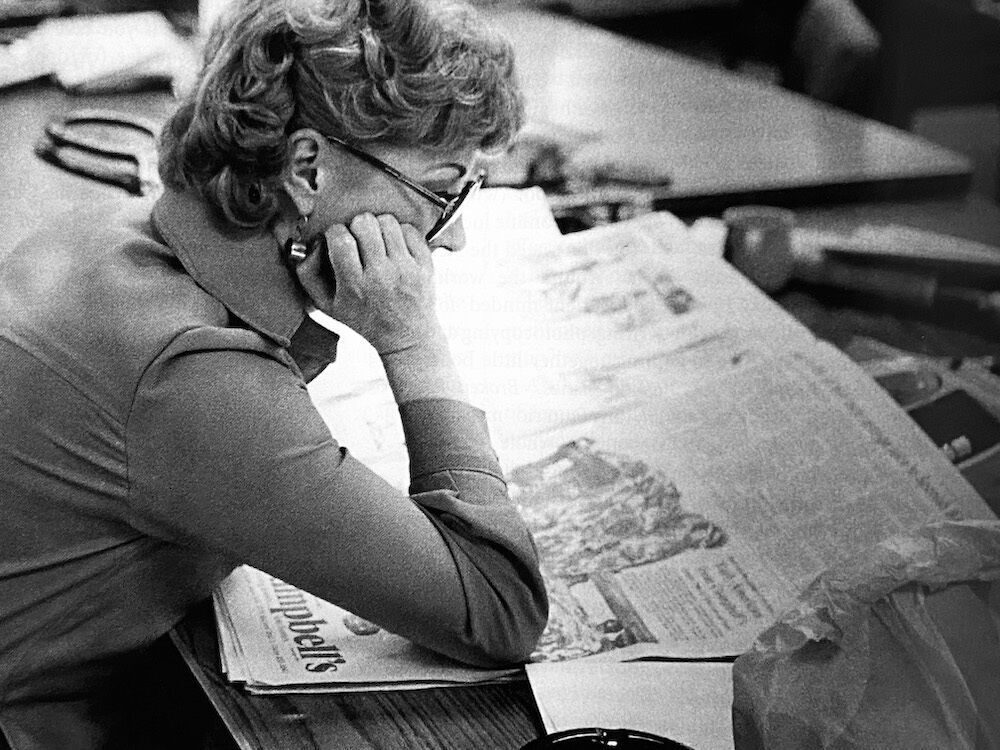

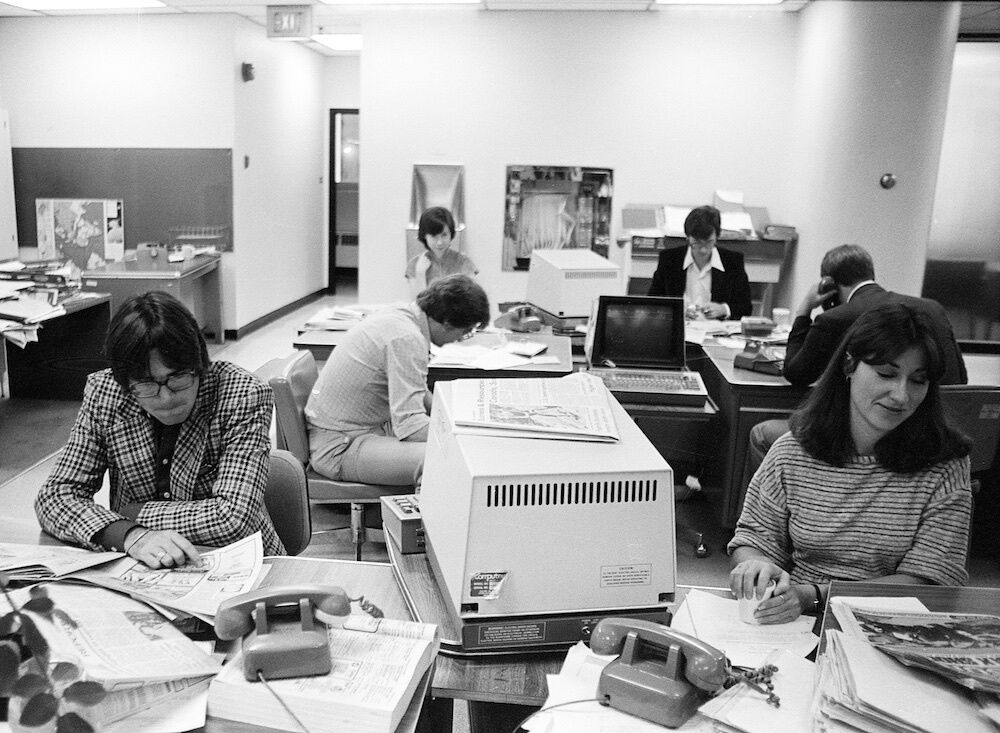

The downtown Calgary Herald newsroom in 1977. Photo courtesty of Bob Blakey

The hollowing of the Calgary Herald

What have we lost?

Sprawlcast is Calgary’s in-depth municipal podcast. Made in collaboration with CJSW 90.9 FM, it’s a show for curious Calgarians who want more than the daily news grind.

This episode is also available as a limited-run, 64-page hardcover book. The Hollowing of the Calgary Herald is part of Hingston & Olsen's Permanent Record longform series, which is "dedicated to standalone non-fiction features that combine inventive storytelling, careful reportage, and characters and ideas that are worth preserving."

If you value in-depth Calgary journalism, support The Sprawl so we can do more stories like this one!

CATHERINE FORD: People looked upon the paper as part of their lives. As an intrinsic, informed part of their daily living.

VICKI BARNETT: My dad came home—he was a teacher—he came home every night, and he read the Herald from one end to the other. So it built a sense of community...

SHELLEY YOUNGBLUT: And the Herald was more than just another outpost in a nationwide chain. The Herald was unique. Until it wasn’t.

JEREMY KLASZUS (HOST): It was once likened to a castle on a hill. For more than 40 years, the Calgary Herald’s big brick newspaper plant has loomed over Deerfoot Trail north of Memorial Drive, a bold expression of the newspaper’s former power. But in January, Calgarians got some news about… well, the news.

CITYNEWS (TAYLOR BRAAT): The iconic Calgary Herald building will soon be no more. Postmedia has sold the building that has overlooked Deerfoot Trail for decades to U-Haul for more than $17 million.

For the first time in its 140-year history, the Calgary Herald has no fixed address.

KLASZUS: In 2020, U-Haul bought the former Calgary Sun building, a little further north on Deerfoot Trail. And now U-Haul is going to convert its newly-purchased Herald building into more than 700 storage lockers. Calgarians have less local news, but more space to stow their stuff.

And for the first time in its history, the Calgary Herald has no fixed address. Today, there are about 10 cityside reporters working for the Herald and the Sun, covering the goings on of the city. That’s way down from what it used to be. In the 1980s, there were about 35 Herald reporters covering the city—and that was just the Herald. The Sun had another newsroom of reporters doing the same thing. Now it’s down to just 10 between the two papers.

GWENDOLYN RICHARDS: Smaller staff equals more “churnalism.”

KLASZUS: This is former Herald reporter Gwendolyn Richards.

RICHARDS: More just trying to feed the goat, as we would always say, and less investigation. Less deep diving.

KLASZUS: What’s happening in Calgary is not at all unique to this city. Journalism everywhere is in trouble, particularly newspaper journalism. The industry faces an economic crisis—and on top of that, a crisis of public trust.

But the decline of a city’s major newspaper has specific local implications.

Over Calgary’s history, there have been many publications that have popped up and served the city for a time. The Eye Opener (1902 - 1921). The North Hill News (1954 - 1981). Fast Forward Weekly (1995 - 2015). Metro (2007 - 2018). The Sprawl (2017 - ????). Each of these publications has shaped the city’s sense of itself in some way.

But no local publication has had the power, influence and longevity of the Calgary Herald. Day in and day out, the Herald has reflected the mores and values of the city—and reinforced them. And smaller newsrooms, including TV and radio, usually followed the Herald’s lead. The Herald set the news agenda for the city.

The decline of a city’s major newspaper has specific local implications.

It’s hard to overstate what the newspaper meant to city life until it was usurped by the internet. It’s how you found out what was happening locally—at city hall or around town. It’s where you went for national and international news. It’s also where you went to find job postings, or a place to live, or to see what people were saying about a contentious issue.

And because most everyone was reading the same pages, it built a common understanding of the city to some degree.

For better or worse, our online information sources today are much more fragmented. We read the stories we want to read, and hear from the people we want to hear from. We no longer look to the paper to understand the city and our place in it.

But it wasn’t always that way.

The old Herald newsroom: 'Everybody smoked, and everybody yelled'

KLASZUS: Catherine Ford grew up reading the paper. Two papers, to be more specific. Her family got both the Calgary Herald and the Albertan, which was the other daily paper in town. (It would eventually become the Calgary Sun.)

CATHERINE FORD: I’m 10 years old, I’m lying on my stomach reading the newspaper. And I thought, well, somebody must be writing this stuff. I thought: I could do that. And so, I did.

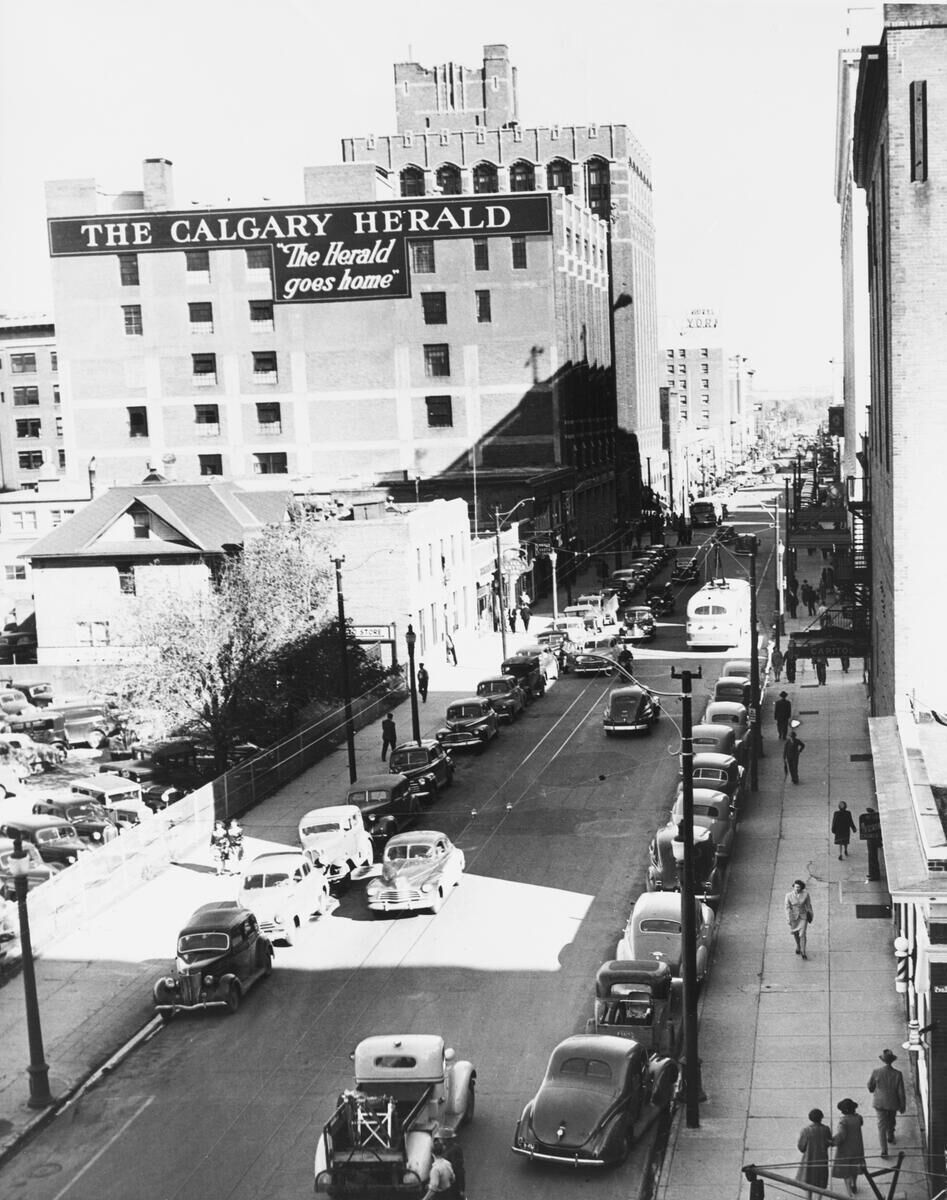

KLASZUS: Ford first walked into the Calgary Herald’s newsroom in 1964. And just to give you a sense of the city at that time: This was before Deerfoot Trail was built. Before there was a Calgary Tower. Calgary had a population of just over 300,000.

And the Calgary Herald was in the heart of downtown, at the intersection of 7 Avenue and 1 St S.W. The paper had been in that building since 1932—and before that, it was just across the street, at the same intersection.

FORD: They made me a junior reporter when I walked through the door. They pointed to some woman sitting in a chair, saying, “I need you to interview her. Here’s your desk, here’s your typewriter.” It was an old Underwood 5 with the open carriage.

KLASZUS: And so Ford got to work—and saw her name in the newspaper that day.

FORD: I wrote this story; I got a byline. I got a byline, the very first thing I ever wrote, and that was it. I mean, I knew what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

KLASZUS: Ford would go on to spend most of her newspaper career at the Calgary Herald. As a reporter, as a widely-read columnist, and as an editor.

The Herald operated downtown for almost a century. The newspaper infamously started in a tent by the Elbow River in 1883, then bumped around to a few different downtown locations before settling at this corner in 1913. And by the time Ford entered the newsroom in the 1960s, it was a bustling place. A loud place.

FORD: You walked into this magical place full of drunks and men.

KLASZUS: In those days, the newspaper was written pretty much entirely by men.

FORD: There was a women’s department, which I joined. How sexist can that be, having a women’s department? But hey, it is what it is, and it was a job, and they were paying me.

KLASZUS: The newsroom was full of clamour as reporters hammered out their stories on these Underwood typewriters. And when they were done, their stories would be sent to the presses by way of a tube system that ran throughout the building.

FORD: It was noisy because of the pneumatic tubes. The copy editors would roll up the paper, put it in a pneumatic tube, and send it down to the back shop to be set into type. And everybody smoked, and everybody yelled.

It was—I hate to use the word romantic—but you felt that you were really part of something alive and important. Because where else did you get the news? Yes, of course there was radio. But everybody took the newspaper, and everybody read the newspaper, and everybody wrote to the newspaper.

KLASZUS: Of all the media outlets in the city, the Herald enjoyed a uniquely prestigious position. It was the establishment paper in an establishment city, and staff used to joke about it being the opposite of an underdog publication.

ROBERT BRAGG: It was called the paper of record, I guess. We called it “the fearless champion of the overdog.”

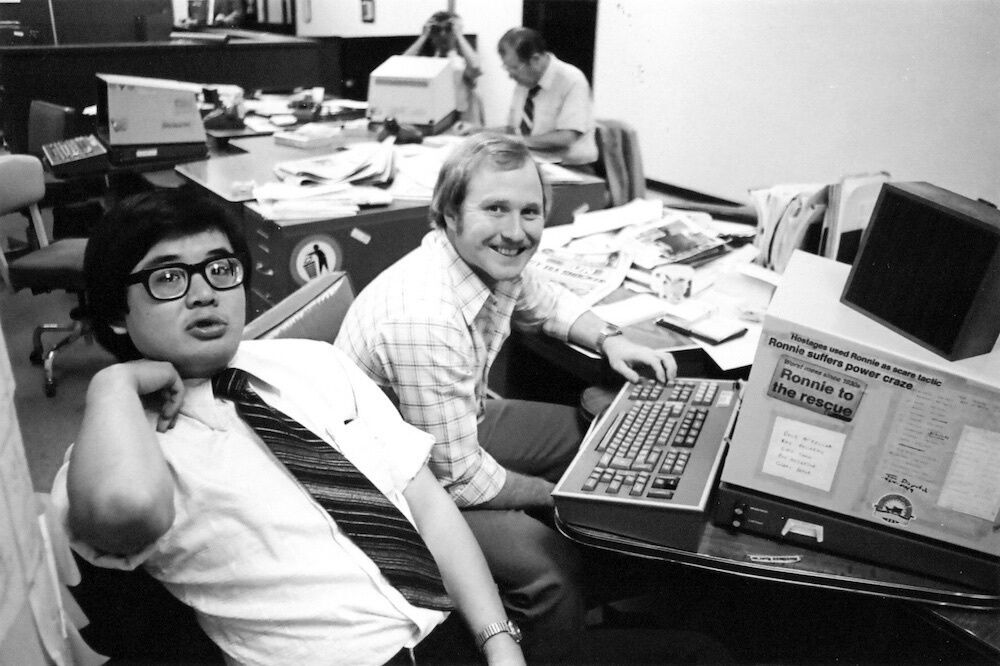

KLASZUS: This is Robert Bragg, who started as a reporter at the Herald in 1973, when the paper was downtown. Thirty years later, he taught me journalism at Mount Royal College. He was one of my profs. I can remember covering a political speech at Mount Royal and then going back to the student newsroom—and Robert behind me saying, “Okay, let’s see some copy.” And I didn’t know what that word meant. Copy? Are we copying something? No, Robert explained to me, copy is just what we call the written text that goes into the newspaper.

But you just heard Bragg use another journalism phrase: “paper of record.” And that meant the Herald was the largest newspaper in the city. The paper that historians would look at years later to find out what was going on.

It was — I hate to use the word romantic — but you felt that you were really part of something alive and important.

And the Herald had a particular approach. You heard Bragg call the Herald the “fearless champion of the overdog.” The Herald reflected, and amplified, Calgary’s identity as a corporate city of oil and gas offices.

BRAGG: The Herald was, and always has been, and probably always will be, reflective of the kind of slightly right-of-centre conservative business class in Calgary. And that was reasonable to expect. I mean, they were the ones who were paying for the advertising, and the cars, and the car dealers. So there was a lot of endorsement of the policies of conservative governments, of the conservative approach to the world. And that was pretty normalized in Calgary, and I think the Herald helped to normalize it.

The Herald wasn’t completely off the charts on the right wing. It had labour coverage. It had advocates for social progress. They were more progressive conservative than, say, the current versions of conservatism, which tend to drop the progressive.

A rivalry between two daily papers

KLASZUS: So that was the Herald. But there was also that other daily newspaper in town: the Albertan. It was the smaller paper that had its newsroom on the west end of downtown on 10 Ave. at 8 St. S.W.

The Albertan viewed the Herald as this big, fat, bloated cat that was just too arrogant for words.

BRAGG: The Albertan and the Herald were kind of frenemies, I guess you’d say. Together, they covered the city. They had people covering the major institutions of the city—police, city hall, provincial and federal politics, healthcare, education, that sort of thing.

KLASZUS: And, of course, business. This was called beat coverage—where reporters were put on specific beats. And it gave both of the papers their depth.

GILLIAN STEWARD: So you actually had people who knew the field, right? And they weren’t just thrown in for a day, and then taken off to do something else.

KLASZUS: This is Gillian Steward, who was a reporter at the Albertan early in her journalism career.

STEWARD: So they knew the field and they could challenge people who were trying to get one over on them or whatever, or who didn’t know the history.

KLASZUS: After working at the Albertan for a year, Steward moved to the Herald in 1973. She’d go on to become the paper’s managing editor in the late 1980s.

STEWARD: The Herald was well known as the newspaper in town, right? It was way bigger, it had much more influence, it was more serious.

KLASZUS: There was another key difference between the two papers at the time: the Albertan was a morning paper. And the Herald came out in the afternoon. But there were other differences too. The Albertan was more scrappy.

STEWARD: It was very much the underdog paper. And so, if you worked at the Albertan, you always relished if you could beat the Herald reporters on a story—even if you only did it not that often. But yeah, there was that sense of, we got the scoop, or we beat them, and they’re so boring, and we’re more interesting, and that kind of thing. Yeah, it was very much a competition that way.

BRAGG: I think the Herald viewed the Albertan as a farm team. The Albertan viewed the Herald as this big, fat, bloated cat that was just too arrogant for words—and no fun.

BOB BLAKEY: The Albertan was a little more edgy. The Herald was quite conservative.

KLASZUS: This is Bob Blakey, who joined the Herald as a reporter in 1978.

BLAKEY: There was one story in particular; this would be around 1980. A man was on trial for murder—I think it was murder. Maybe it was just assault. But he held a victim at gunpoint, cut the guy’s testicles off, and fed them to his dog. The Herald would not run any of that. It just said the man was mutilated. Well, the Albertan ran all of the details! So it was kind of an edgier paper.

KLASZUS: In 1980, the Albertan was bought by the Sun newspaper chain—and the Calgary Sun was born. Now, the Herald was a broadsheet, which meant it had long vertical pages. The Sun was a tabloid, which meant it was more compact. The Sun more right-wing than the Herald—and generally speaking, it appealed more to the city’s working class than the Herald did.

There’s a certain expectation of a tabloid newspaper. And that is: tits and ass, scandal, and the monarchy. And more scandal.

KLASZUS: One of the Sun’s main selling features was the Sunshine Girl, the pinup photo that ran daily at the front of the paper. And this approach was largely inspired by tabloid journalism in the U.K.

FORD: If you’re a tabloid, there’s a certain expectation of a tabloid newspaper. And that is: tits and ass, scandal, and the monarchy—and more scandal. So, your front page is going to be completely different than the front page of the grey, old broadsheet, which actually deals in real news.

KLASZUS: The Albertan, and later the Sun, hated and relished the stuffy condescension of the Herald. People at the Sun called the Herald “the velvet coffin”—while at the same time trying to get hired there.

FORD: It's so arrogant of me to say this. But seriously, we used to think, “Well, when you grow up, you can come and work for the Herald. If you've had experience at the Sun, that means yes, you can come and work for us.” Which is exactly what happened.

KLASZUS: The newsroom pace was a lot more luxurious at the Herald. You got paid better, and you had more time to work on stories. You didn’t have to crank something out every day like you did at the Sun.

BLAKEY: The paper was so rich that they could afford to let you spend a week or two weeks on a story.

KLASZUS: So these rival newspapers competed fiercely to document the ups and downs of life in a city dominated by the oil industry.

BRAGG: Boom and bust—those are the only two stories that I felt like we covered for 25 years. It’s either a boom or a bust. And if it was a boom, all of the stories had boom angle. If it was a bust, it was all the same thing. So every story had some kind of consequence based on the fact that the economy was tanking, or it was exploding and booming.

The revelries of a downtown newsroom

KLASZUS: When the Herald was downtown, the newsroom was... a boozy place.

BRAGG: When it was an afternoon paper, your deadlines were at like 10:30, 11:30 in the morning—or even 8:30 for early morning rewrites, which I did for a couple of years. Basically your job was over by noon, or it was over for that part of the day. You could go for lunch at the Empress. And some people would go for lunch and not come back.

KLASZUS: The Empress was an old hotel with a beer parlour.

BLAKEY: The Empress was very, very conveniently located. It was right across the alley from the Herald. The Herald was on 7 Avenue, the Empress was on 6 Avenue—and there was just a narrow alley between the two. And there was a back door to the entrance.

FORD: So we’d walk out the back door. We’d take one of those thick copy pencils that are twice the size of an HB pencil, and we’d slip it in the door. There was no way to get back in through that door, because there was no handle on the outside. So we’d prop it open with a pencil, go and have a few beers, and come back to work. And that was quite normal. And any reporter worth his or her salt, knew that if you wanted to find an editor at about two o’clock in the afternoon, you just went straight to the Empress Hotel pub.

BLAKEY: And the Herald had a cluster of small tables at the back, right where you came in, so the Herald people didn’t have to walk very far. There was their table. And it ranged anywhere from four to 15 people at any given time. We’d talk about the paper, what the day was like, and all kinds of stuff.

STEWARD: A lot of us, particularly women on staff, used to get upset about the bar thing going on at the Empress. Because if we had to go home or whatever, do other things, so many of the staff would go down and talk business. They would make some decisions down there, right in the bar. And if you weren’t part of that, you got left out, which made a lot of people mad—well, a lot of women mad anyway.

I think Calgarians in general felt way more connected to the newspaper because they literally used to walk in off the street.

KLASZUS: So that’s what was going on out the back door. But what really connected the Herald to the lives of Calgarians was the world outside the newspaper’s front door: the human bustle and everyday life of the city.

STEWARD: You’d walk out of the Herald building, and there was the Bay across the street, and then Knox United Church. The Greyhound bus depot at one point was actually across the street where the Telus building is now. So, you felt like you were in the heart of the city, and that you were really a big part of the city, an important part of the city.

And I think Calgarians in general felt way more connected to the newspaper because they literally used to walk in off the street, into the newsroom, if they wanted to see a particular reporter or an editor or whatever. They’d just come in. I mean, there’s way more security now. That would never happen. But then, people did. And they’d show up with these long sorts of manuscripts or letters to the editor that they wanted in. So it was a symbol of the city, but it was also much more intimate in terms of its relationship with the city, with people.

BLAKEY: It was like the town centre. It was like the busiest corner in town. People used to come in and just talk to you. They’d be ordinary people, they’d be politicians, they’d be cops. It was like a meeting point where you could discuss issues. And we all used to do most of our interviews in person.

FORD: You’re walking along 7 Street, and you see something happening. You’re in the restaurants downtown. You’re in the Hudson’s Bay Company buying makeup. You felt that you were a part of the city’s heart.

Fleeing downtown for 'the boonies'

KLASZUS: But Calgary was changing. As the city sprawled outward, downtown was getting more jammed with cars. In 1975, Herald journalist Bob Shiels wrote that Calgary had “more vehicles per capita than anywhere else”—including American cities such as L.A.

BRAGG: I think there was a feeling that the city would keep growing and sprawling, as it has, as even your paper reflects—the name.

KLASZUS: And as the city grew, the Herald started to look at decamping from downtown.

BLAKEY: And Frank Swanson, who was the publisher, he was due for retirement. And you know how a lot of politicians and business people think about legacies—what’s my legacy? His legacy was going to be this new building, the grand Herald. Just way better than anything they had downtown.

Those of us who worked there didn’t mostly like that at all. We said, you know, “everybody we need to talk to, practically, is downtown. Certainly, all of the officials. It’s going to be inconvenient as hell.” And they said, “Oh, no, we’re going to have a shuttle bus, a daily shuttle bus twice a day to bring anybody downtown. And of course, you can use any cabs you want” and all this kind of stuff. The shuttle lasted about a month after we moved.

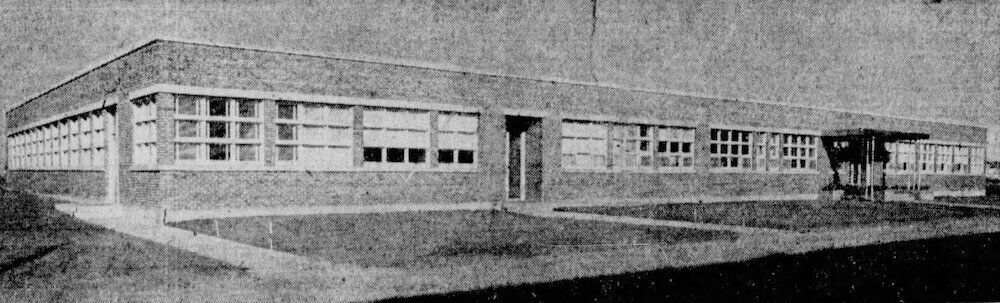

In 1981, the Herald gave up its walkable, streetfront newsroom and moved into a giant newspaper plant next to a couple of freeways.

KLASZUS: The Herald was running into major logistical problems downtown—in part because of its afternoon publishing schedule.

FORD: The reason the Herald moved was really simple. Downtown Calgary was so busy and so active, they couldn't get the trucks out and through the traffic to deliver the newspaper.

KLASZUS: In the 1970s, the Herald had over a thousand newspaper carriers. These were mostly kids who would deliver the newspaper after school. And these young workers were crucial in getting the news into the hands of Calgarians.

But if the presses were running late, traffic snarled around the Herald building. Trucks would stack up in the alley, and circulation workers would have to tell the drivers to drive around the block and then come back for the day’s papers. And then, after the trucks were loaded, they’d be stuck in rush hour traffic.

All of this was rather unpleasant. So in the most Calgary move possible, the Herald gave up its walkable, streetfront newsroom and built a giant newspaper plant next to a couple of freeways. The paper bought 13 acres of land overlooking Deerfoot Trail and Memorial Drive, not far from the railway tracks.

When the Herald had been downtown, it had to store newsprint at different warehouses around the city. Now the Herald built a private railway siding that went right into the new building, and could take in five train cars of newsprint.

The new presses, meanwhile, could crank out about 90,000 papers per hour. The Herald had a circulation of about 150,000 at the time of the move.

In its own pages, the Herald called the new building a “sprawling red brick ‘castle on the hill’” and boasted about having one of the largest newspaper operations on the continent. Publisher Frank Swanson, who was about to retire, liked to boast of it being the length of two football fields.

When the Herald moved from downtown in 1981, the paper was more or less at the height of its power.

For almost all of the 20th century, the Herald was part of a Canadian newspaper empire called Southam News. Being the main newspaper in an oil and gas town, the Herald was uniquely profitable in the Southam chain. By the time the Herald moved to the new building, it had about 800 staff across all departments.

BRAGG: The Herald was a big log, especially on weekends, to thump onto your doorstep. You had to have delivery systems. You had to have advertising salespeople. But mostly, yeah, you had to fill around the ads. So you needed news stories to go with it.

STEWARD: Some Saturday papers were so fat with advertising, you could hardly pick them up. And they were having to hire more people, more reporters and more editors on the desk, because they had so much space to fill. The Edmonton and Calgary newspapers for Southam made the most money. They were just rolling in dough.

A new era of 'splendid isolation'

KLASZUS: After the Calgary Herald moved into its new building in Mayland Heights in 1981, something changed. Well, a lot of things changed.

BRAGG: The Herald, when it moved out of downtown, became a commuter building. An office building where you were just basically driving to work, and driving home.

FORD: Reporters started doing more of their connections on the telephone, rather than in person because it wasn’t as easy as just sticking on your coat and walking to the courthouse, or walking across the street.

If you move up to the boonies, which really was where that building was at the time, there’s a disconnect.

BRAGG: There was some grumbling of course, and a lot of, I think, real sadness about being out of the core, and having to—"we’re only a cab ride away," kind of stuff. But it wasn’t the same as just being able to walk out and mingle with the folks, and be part of the city action; feel part of the city action. It wasn’t the same after that.

VICKI BARNETT: Moving up to that big building on the hill was not good.

KLASZUS: This is Vicki Barnett, who was a Herald reporter at the time of the move.

BARNETT: Because when we were downtown we were instantly connected to everything going on downtown. And we found out about it very, very quickly. The police are downtown. The main fire station is downtown. And if you move up to the boonies, which really was where that building was at the time, there’s a disconnect.

KLASZUS: Even the paper’s own reporting on the move acknowledged this disconnect. Columnist Bob Shiels wrote that “the new plant sits on top of the hill in splendid isolation.”

The Calgary Sun followed suit in decamping from downtown shortly after—also moving right beside Deerfoot Trail, a little further north than the Herald, in 1982.

Now, there were some upsides to the new digs. Less alcoholic self-destruction, for one thing. Bob Blakey heard about this when he eulogized the old Herald building for Fast Forward Weekly before the old building was demolished in 2013 to make way for a new skyscraper: Brookfield Place.

BLAKEY: One reporter told me there was major liver regeneration when the Herald moved because there were people on the verge of death. One guy actually did tell me, “That saved my life, literally, because I was heading for a bad place.” But you get up in Mayland Heights and there’s nothing, nothing! I mean, you can drive but nobody really wants to drive to get drunk. So that made a big difference to the culture.

KLASZUS: The new location did make it easier to drive around the city. And anyone who worked in that newsroom will tell you that the building had the best views in Canadian journalism.

BLAKEY: There was an interesting optical illusion: If you stood at the very back of the newsroom, as far away from those windows as you could, the mountains filled the windows. It looked like they were just down the road! And we’d say, “Oh, look at that sunrise.” You didn’t get that in the old building. There were hardly any windows in the old building.

KLASZUS: There was originally going to be an auditorium in the new building, but that quickly got converted into on-site child care.

FORD: There was nothing around except the parks department. It was a warehouse and residential district. So, of course, because no one bothered to rent the auditorium, someone, I think it was the HR director at the time, had the bright idea to turn it into a daycare centre. That was brilliant. I can remember the faces on some of the female employees who were of childbearing age and having children—what a relief it was. It wasn’t cheap, but it was there. They could bring their children to work. They could visit their children during the day.

KLASZUS: By the end of the 1980s, the two top editors at the Calgary Herald were women. Gillian Steward was the paper’s managing editor. And Catherine Ford was associate editor, responsible for the editorial and opinion pages. In other words, women were running both the news side and the opinion side of the paper.

By the end of the 1980s, the two top editors at the Calgary Herald were women.

STEWARD: The whole effort, or the whole—what’s the word I’m looking for—was run by men, for men, and nobody thought anything should be different. That’s just the way it was. And I think there became, as with a lot of women at that time, just became a growing awareness that it didn’t have to be like that.

KLASZUS: And they had a publisher who supported them and backed what they were doing.

STEWARD: When J. P. O’Callaghan was the publisher—he came up the ranks from journalism. And so that was very much his first concern. And I remember so well, if we were doing anything sort of investigative or edgy, he’d say: “Well, if you do it right and you have everything—you have all your facts down—do it. And if we need lawyers, because they’re going to sue us anyway, you have lawyers.” You felt like your back was covered. And so that encouraged people to do more risky things.

BARNETT: They were promoting women and giving them excellent beats. It was a good time to be in the news business—the best time.

You felt like your back was covered. And so that encouraged people to do more risky things.

KLASZUS: J.P. O’Callaghan believed that a newspaper should have its own independent flair rather than copying other papers. When O’Callaghan took over as publisher of the Herald in 1982, he did it in his fighting style, disparaging the Sun as a “formula newspaper.”

But as the decade wore on, the Herald was already facing daunting questions about its future.

STEWARD: I think a lot of people look back now and think, well, we moved into the new building in the ‘80s, and it was like everything just went downhill from there. Not because of the move, but just because of what was happening with newspapers, and new kinds of media coming on. Television had been number one for news in terms of audience for a long time at that point. So it was kind of on the decline anyway.

BRAGG: The economics of newspapers was changing. Advertising was changing. And the Herald had always been a cash cow for the chain, so to speak. They didn’t call it a chain; they called it a group. But it was a chain, and the money wasn’t staying in Calgary. The huge amount of profit that the Herald was generating was going elsewhere.

KLASZUS: In 1985, the Herald switched from being an afternoon paper to being a morning paper, delivered to your doorstep by 6:30 a.m. Newspapers all over were making this switch at the time. But the Herald’s transition was also, in part, because of societal change. More than half of Calgary women were out working during the day. “They want a morning newspaper,” publisher O’Callaghan wrote, “so that they can shop the bargains and make a purchase in the afternoon if something takes their fancy.”

That was the theory, anyway.

In the morning, women didn’t have time to read the newspaper. They were going to work, going to school, getting their kids ready.

STEWARD: And then it became a morning paper, and in the morning women didn’t have time to read the newspaper. They were going to work, going to school, getting their kids ready, whatever. And so, they were worried about that. There were all kinds of marketing surveys that went on. How are we going to get readers back, all that kind of thing, because the decline had started already. And so, they really wanted to get women readers back, or in, or whatever.

KLASZUS: By the late ‘80s, the Herald’s independence as a local newspaper was beginning to crack. Southam always made it a point of pride that its papers had always been completely independent editorially. Publishers and editors didn’t have to worry about out-of-town meddling. The Calgary Herald could do as the Calgary Herald saw fit. But now Southam’s head office in Toronto was starting to call more of the shots—and to cut costs.

Here’s what O’Callaghan wrote in his memoirs: “After a century of virtual autonomy—at least with the editorial product—the newspapers were now firmly under head office direction, with the power and the initiatives of the publishers miserably curtailed. Individualism was banned, replaced by groupthink and centralized task forces that sprouted like summer weeds in the greenest of lawns.”

To drive home his point, O’Callaghan borrowed a metaphor from former New York Times executive editor Abe Rosenthal, who had once likened publishing a newspaper to making soup. You could choose to add more water or add more tomatoes—and in the 1970s, under Rosenthal, the New York Times chose to add more tomatoes.

But to his dismay, O’Callaghan saw Southam starting to do the opposite. “The days of adding tomatoes to the soup were over,” he wrote, “and many of the newspapers took on the appearance of a bowl of thin gruel.”

After a century of virtual autonomy — at least with the editorial product — the newspapers were now firmly under head office direction.

Boosterism the and the mythology of Calgary

KLASZUS: Newspapers have historically performed two functions that seem to be in contradiction. There’s the watchdog role of the paper: holding powerful people and institutions to account, and looking at the world with a critical eye. Keeping politicians honest. This is the version of the newspaper you often see in movies: the paper as a check on corruption and wrongdoing in a democratic society.

But it’s also true that newspapers have also been enthusiastic boosters of the cities they serve. The Herald tended to give powerful institutions like the Calgary Stampede favourable coverage, rather than doing much that was critical.

STEWARD: Calgary is very... what I would call booster-ish, right? We like to think of ourselves as kind of being more optimistic, more get-on-with-it kind of people. And certainly, the Herald would have promoted that. Part of it being like the way we covered the Stampede, that sort of thing. But there was also that sense of: we can do this, we’re great, and this is a special city.

KLASZUS: The idea of Calgarians as mavericks, as entrepreneurial, as people of western hospitality—these elements of civic identity were all woven into the paper, day in and day out.

There is a mythology to Calgary… Part of the day-to-day reporting of the paper often was to maintain that mythology.

KLASZUS: Sasha Nagy learned this firsthand when he joined the paper in 1990, moving from the Vancouver area. Calgary was still basking in the afterglow and civic pride of hosting the Winter Olympics in 1988. And for Nagy, joining the Calgary Herald was… an adjustment.

SASHA NAGY: Learning the mores and the ways, and the customs, and the language, and all that stuff was so foreign to me, because I’d never lived in Alberta before. Well, that’s not true. I lived in Northern Alberta for one year. My dad was a doctor in the armed forces in Cold Lake one year.

But there is a mythology to Calgary that I was learning as I went, you know? And part of the day-to-day reporting of the paper often was to maintain that mythology, or to sort of expand on that.

The strike of 1999/2000

KLASZUS: The Herald took a sharp rightward turn in 1996, when Conrad Black’s company, Hollinger Inc., bought the Southam papers. These included the Herald, the Edmonton Journal, the Ottawa Citizen, the Montreal Gazette, and the Sun and the Province in Vancouver.

BLAKEY: The real deathblow I think to the quality of the paper, was when Conrad Black took it over.

KLASZUS: A little over a decade later, in 2007, Black would be convicted and jailed in the United States for fraud. But… this was before all that.

BLAKEY: He loved journalism, but he didn’t like journalists. His attitude was, these people are in a fat location, they’re on an easy ride, just a cushy number. They’re overpaid, they’re underworked. So the pressure was on to get rid of people, and then there were more people bought out.

KLASZUS: That same year, Ken King became publisher of the Herald. Calgarians today might remember King better as the former president and CEO of the Calgary Flames; he died in 2020. But King used to be in newspapers. He’d been publisher of the Calgary Sun before joining the Herald in ‘96.

BLAKEY: And he really started to make some bad changes. He brought in some people from the Sun who had a very different attitude. They were quite right-wing, and they also were anti-journalist. I think some of those senior managers just felt that we all had it too easy. And so, people were shoved out the door. People, one by one, were picked off.

STEWARD: The publisher at the time, Ken King, was really keen to present the Herald as part of the business community in the sense of: okay, no, we won’t tackle that subject if it’s going to embarrass you. Or we won’t write anything negative about the Flames because we want to be with them. We want to be a sponsor, and we want to be seen to be a part of that organization. And that really started to bother people. They were being told not to cover certain things, or not to say certain things.

KLASZUS: Tensions grew between newsroom employees and management. In 1998, Black launched a new national newspaper, the National Post, to compete with the Globe and Mail. Black’s project was largely subsidized by the Herald and other profitable newspapers in the chain, which created additional bitterness toward the new owner.

KLASZUS: The Herald also became more ideologically right-wing at this time. Danielle Smith joined the paper as an editorial writer on the opinion pages. This was in 1999, right after after Smith’s short-lived tenure as a public school board trustee. The provincial education minister had fired the entire board because it was so dysfunctional. The Herald immediately gave Smith a place to land—and the rest is history.

Meanwhile, reporters were increasingly frustrated with so-called “drive-by” editing, as managers would change reporters’ stories—often adding inaccuracies—after they’d gone home for the day. Midnight mangling, they called it.

All of this roiled the newsroom. Tensions reached a breaking point in November of 1999 after newsroom employees voted to unionize, and then went on strike.

The strike dragged on for eight months, and the paper’s journalistic integrity was one of the key sticking points, along with job security. At one point, the famously verbose Conrad Black referred to the striking journalists as “gangrenous limbs” that needed to be amputated, and accused them of trying to stage an NDP coup in the newsroom.

People at the Sun, meanwhile, enjoyed the fireworks as the Herald strikers denigrated the paper as the “Calgary Horrid” from the picket line. The striking workers encouraged Calgarians to cancel their Herald subscriptions in support of the newsroom staff.

KLASZUS: The strike finally ended in the summer of 2000 with the union defeated. The Herald offered the strikers buyouts, which most of them accepted. This was a turning point for the paper—there’s the pre-strike era of the Herald, and the post-strike era. The Herald had lost many of its subscribers, and was now losing most of its institutional memory.

BRAGG: [It] dealt a real body blow to the Herald as an institution, and to the people who ended up losing their jobs, and their careers, and having to move into something else.

KLASZUS: After the strike ended, Black sold the Herald to another media mogul, Izzy Asper. Asper’s company was called CanWest Global Communications, which included the Global TV network. And by now, the Herald’s independence was a thing of the past.

Asper would introduce the dreaded “national editorials”—where all papers in the chain were forced to run the same editorial in the opinion pages, a directive that came from head office.

CanWest papers were also expected to hype up the TV show Survivor, since it was a Global show—and to fudge local TV ratings if they didn’t make Global look good.

Blakey was the Herald’s TV columnist at the time and pushed back on his stories being rewritten to cast Global in a glowing light when CTV actually had better local ratings.

BLAKEY: And I said, “That’s bullshit! You just can’t do that.” He said, “Yes, I can Bob, this is the new order. You gotta get used to this.”

After the strike: 'The beginning of the end'

KLASZUS: I met Gwendolyn Richards in the parking lot of the Herald building after news broke that it had been sold to U-Haul. She hadn’t been back there since January 2016, one of the darkest months in the newspaper’s history.

RICHARDS: Honestly, it feels a little strange. I have not been anywhere near this building since I was laid off. I basically got a couple days grace and then I came back and packed up my stuff. And then, you know all those images from the movies where you drive away and it explodes behind you? That’s kinda how I felt when I was driving off. Like, I’m done here.

KLASZUS: Richards started at the paper in 2004. By then, the acrimony of the strike had mostly subsided.

RICHARDS: It sort of, I think, was the beginning of the end of the heyday of journalism. It was just as things started to get cut back. Travel for stories, those sorts of things were all being scaled back. So, I kind of feel like I got in right at the start of the decline.

KLASZUS: The paper was doing some impressive journalism, like its dogged coverage of a ballot-stuffing scheme in the 2004 civic election. But pretty soon there was another round of job cuts.

RICHARDS: And I think we didn’t really have any sense of it then—that that was just going to be the start of what would be a death by a million cuts.

KLASZUS: By now, newspapers everywhere were in major trouble. Advertising dollars went online. Classified dollars went online. Readers went online. Newspapers tried to follow online—but struggled.

CanWest Global went bankrupt in 2010, at which point Postmedia bought the Herald and other papers in the chain.

And if it was bad before—it was about to get a whole lot worse.

While the Herald’s owners have historically been Canadian companies, usually with at least some level of pride in local journalism, Postmedia is owned by U.S. hedge funds. And hedge fund ownership has been disastrous for newspapers, both in Canada and in the States. Hedge fund owners have been sucking the little remaining life and money out of newspapers as they collapse. Meanwhile, Postmedia has been collecting federal subsidies for journalism—the so-called media bailout—while still paying out massive executive bonuses.

Hedge fund ownership has been disastrous for newspapers, both in Canada and the U.S.

RICHARDS: Was it because we were taken over by another company? Essentially we were sold to a bunch of investment people in the States, who had very different goals out of owning a media chain—or if it was just a sign of the times of the decline of journalism. Because all of these factors are playing into it, right? The decline of ad sales because of the internet. Craigslist coming in and demolishing classified ad sales. Paper prices going up.

KLASZUS: But even 12 years ago, the Herald still had significantly more clout than it does today. I was involved in the paper by this time—never as a staffer, but as a freelancer for Swerve magazine and as a freelance opinion columnist. I live on the other side of Deerfoot Trail from the Herald, and when walking on the ridge overlooking Nose Creek, I’d often look across the way and see the Herald building blazing red in a spectacular sunset. I’d always wonder what was going on inside—what stories were being chased.

But it was probably a good thing that I was observing from afar. On the inside, the newspaper was being picked apart.

YOUNGBLUT: The cuts inevitably came to the Herald.

KLASZUS: This is Shelley Youngblut, who founded and edited Swerve magazine, which was part of the paper on Fridays from 2004 to 2018.

YOUNGBLUT: And so, one by one, these departments... I think those of us who worked at the newspaper understood how important they were for community. I mean, there were the people that worked in the distribution area where the printers were. The flyer force people; these were people that came in and stuffed your Friday newspaper full of flyers. That was outsourced. Ad building was outsourced. The daycare was closed. There were a couple of people still at the cafeteria, but the actual food services were no longer—it was outsourced.

I think we didn’t really have any sense of it then — that that was just going to be the start of what would be a death by a million cuts.

KLASZUS: Page layout and copy editing was outsourced from Calgary to a Postmedia operation in Hamilton. All the Postmedia big-city papers got stripped of their individual branding, which was specific to each city. Now all of the papers had to use a one-size-fits-all template. Meanwhile, the actual printing of the Herald was also outsourced.

YOUNGBLUT: And I remember the day they came and they closed the press and they started packing it up and they put it on a railway car and they shipped it somewhere. Yeah, it was like watching your lungs get ripped out of you.

There is something about having a news organization rooted right in the heart of the city. And then, when the Herald moved onto this big stone, brick building, it was this monolith. Every time you went up and down Deerfoot Trail, there it was.

And it’s almost like you could look at the side of that building and tell the story. At one point, it was the Calgary Herald proud. Then they added the National Post, so now you’ve got these two entities. And then, all of a sudden, the letters would start falling off. So, it’d be like, they’d lose an R, or they’d lose an L.

YOUNGBLUT: And then at one point, they wanted to celebrate some of their most high profile journalists, and so, my good friend, Val Fortney, there she was like Sarah Jessica Parker on the side of a bus, except she was on the side of the Calgary Herald building.

And then, that got replaced by a “for sale” sign. And that “for sale” sign was up forever. And I don’t know if that’s the greatest billboard you want publicizing how important your newspaper is to a community, to the most trafficked highway in Calgary.

The rivalry ends: Merging the Sun and the Herald

KLASZUS: The Herald and the Sun were rivals for more than three decades. And far longer than that, if you count the Albertan years. But all of that changed in 2014.

CTV NEWS (ZURAIDAH ALMAN): In a world where newspapers are struggling to remain profitable, it is a merger executives say designed to secure the future of the Canadian newspaper industry.

ROD PHILLIPS: Today's a great day for made in Canada journalism. And in our view, it's the best way forward.

KLASZUS: That was Rod Phillips, Postmedia’s board chair at the time. Postmedia was buying the Sun chain—including the Calgary Sun.

CTV NEWS (CRISTINA HOWORUN): This deal shows just how much the newspaper industry is hurting. Only 15 years ago, Quebecor bought virtually the same bundle of newspapers from Sun Media for more than three times the amount being paid today. But Postmedia says it's a deal that allow newspapers to keep printing.

KLASZUS: The Calgary Herald and Calgary Sun would now be owned by the same company. For anyone familiar with the news industry, all kinds of alarm bells went off. You don’t want the same owner for both daily newspapers in a city. But Postmedia’s CEO at the time, Paul Godfrey, argued that because of the internet, newspapers were no longer competing with each other, but with American tech companies.

PAUL GODFREY: We need this scale—and of course, time—to be able to compete with giant foreign-owned digital-only companies like Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Twitter.

KLASZUS: At the time, Godfrey gave assurances that the newsrooms and papers would be kept separate.

GODFREY: We've made a commitment that our plan is to keep the newspapers going... We have nothing planned to close anything.

KLASZUS: The federal Competition Bureau fell for it, saying the “transaction is unlikely to substantially lessen or prevent competition.”

The newsrooms operated separately for a bit—but that lasted just a little over a year.

There was a lot of confusion. How could these two fierce rivals suddenly be in the same company?

CTV NEWS (TARA NELSON): Postmedia—who owns the National Post, the Sun newspaper chain, the Calgary Herald and several other daily newspapers—is merging its newsrooms. It's all part of a plan to find $80 million in savings.

KLASZUS: This was in January 2016. The Calgary Sun would be moving into the Herald newsroom. By now, the Herald was renting out much of its building, and the entire newsroom was small enough to fit in the back room that used to be the Swerve office.

RICHARDS: When it was announced that we were merging, I think there was a lot of confusion. How could these two fierce rivals suddenly be in the same company? And then when they announced that we were all going to be in the same newsroom, we were really befuddled.

KLASZUS: To make it worse, when the newsroom merger was announced, 25 staff in Calgary got cut. Most of them were Herald staff, including Richards, who had been the paper’s food writer. The Edmonton Journal was similarly gutted that day.

RICHARDS: It just feels like my time at the Herald was a long series of saying goodbye to things.

The underdog tabloid had essentially taken over the eviscerated Herald newsroom from the inside.

KLASZUS: The Sun’s editor-in-chief, Jose Rodriguez, was now editor-in-chief of not just the Sun, but the Herald too.

Calgary’s daily newspaper rivalry was officially over. In the end, you could say the winner was the Sun—or what was left of it. The underdog tabloid had essentially taken over the eviscerated Herald newsroom from the inside. The papers continue to be published separately. But aside from having different columnists—Don Braid in the Herald, Rick Bell in the Sun—they’re more or less the same in their local news content.

A year after taking over as editor-in-chief of the Herald, Rodriguez left the newsroom to work for the City of Calgary in communications. Numerous journalists have similarly jumped ship as it sinks, getting out while the getting is good.

The remaining crew of about 10 cityside reporters continues to work away at the Herald and Sun, doing their damndest to cover daily news in the city they live in and care about. They’ve been working remotely since the pandemic began in 2020—and now, with U-Haul taking over the Herald building, they have no newsroom to return to.

FORD: What kind of a sense of community do you have if you're holed up in your own home in front of a computer? Who do you talk to when you want to ask a question? You can't just turn to the guy at the next desk. You can't walk down the hallway and ask a question of a certain editor. Because you don't have that. So you don't have any sense of belonging to a real group of people—living breathing human beings.

STEWARD: It hasn't disappeared, but it's just a shadow of its former self. And it seems like it happened so quickly. And nobody was really prepared for that.

Propping up the power structure in Calgary

KLASZUS: As a journalist, I find it easy to get nostalgic about newspapers—to think that everything was so much better in the old days.

But it’s also easy to over-romanticize it. The reality is that for all its value to the community, the Calgary Herald had significant shortcomings as an institution. The newspaper was a product of the people who made it—mostly white men, until more women were brought on in the '70s and '80s. The newsroom was not a racially diverse place, and the paper reflected that. Calgary has never been as diverse as it is now, but the reality is that the Herald covered some stories faithfully while ignoring others.

Even in its glory days, the Herald lived up to its reputation as a “champion of the overdog.”

We certainly weren’t challenging the powers that be — especially in the oilpatch.

BRAGG: I don’t think they were very good at covering, how would I say, poverty issues, social issues, social welfare questions. There were attempts to get there. Women’s issues, I think, were neglected. A lot of the issues of today that would be in the category of “progressive” were not really covered by the Herald that much.

STEWARD: The Herald, at that time particularly, we weren’t doing what I would call very much investigative journalism. And we certainly weren’t challenging the powers that be—especially in the oilpatch. I mean, there are so many really interesting stories and things happening, and there always is in the oilpatch. We had a lot of business coverage. We had a lot of business reporters. But they weren’t really challenging what was going on. They were reporting on what was going on. They weren’t really challenging it.

The Herald did a good job of sustaining the power structure, I would say. We didn’t challenge it that much. And we were part of it.

BRAGG: So, yeah, fearless champion of the overdog, kind of ignoring the underdog.

How do you measure the slow gutting of a metro newspaper, the largest newsroom in town?

What we've lost: 'A common understanding'

KLASZUS: So what have we lost? We can say the newspaper business failed to adapt to a changing world, and that would be true. But it’s also true that our media diets today are infinitely fragmented by social media—and this means that we are drawing from wildly divergent information sources to form our conception of reality. One person’s “fact” is another’s “fake news.”

And when that’s the case, can we still have a shared sense of identity and purpose as a city?

Margo Goodhand was the Edmonton Journal’s editor-in-chief until she was cut loose in 2016, along with all those other staff at the Journal and Herald that January. Later that year, she wrote a piece for The Walrus about the decline of Alberta’s big-city newspapers. She asked: “How do you measure the slow gutting of a metro newspaper, the largest newsroom in town?”

“Court and crime and car crashes stay in the headlines because they are cheap and easy to cover. What disappears is the substantive stories that contribute to a community’s sense of self and worth…”

“Good journalism is more than a mirror; it also tells communities what they can and should be.”

The Herald no longer has the capacity to set the news agenda for the city like it once did. To the extent that anyone does now, it’s probably CBC Calgary. But the reality is that it’s often social media that sets the news agenda, and newsrooms follow. And there are pluses and minuses to that. It means ordinary people, and particularly those who have been marginalized historically, have more power than they did when a pro-establishment newspaper decided what was news and what wasn’t.

The Herald did a good job of sustaining the power structure, I would say.

KLASZUS: But as reporters are increasingly expected to do more with less, they often find themselves chasing the story of the day, with little time to dig into anything else.

RICHARDS: We don’t know, as a community, what’s going on, to the same ability that we would have 10, 15 years ago. And I don’t think that people understand the impact that has, partly because they don’t know what they’re missing out on.

KLASZUS: As an example, I’ve had people tell me they don’t even know what’s going on at city hall. In a city of almost 1.4 million people, they don’t have a sense of the current mayor and city council. Because they simply don’t have enough information to form a clear conception of it.

That’s something that we took for granted in the past. The Herald would have multiple reporters at city hall. On top of that, opinion columnists would write about city hall. And then citizens would write letters to the editor about local issues. And other media outlets would add to this coverage in their own ways. The Sun and Metro and TV news would try to get “scoop” stories that the Herald wouldn’t have.

And from all of that information, as a citizen of Calgary reading the newspaper, you could form a reasonably clear idea of what was happening at city hall and make up your own mind about it. But if you don’t have that basic information to begin with, it’s significantly harder.

KLASZUS: I asked the people I spoke to for this story what they think we’re losing. And most touched on themes of fragmentation and connection. How we understand each other, this city, and our place in it. And how we talk to each other—or don’t.

BRAGG: I think we’ve lost a public sphere, basically. We’ve lost a consensus approach to what’s real and what’s not—what’s important and what’s not. It’s much more difficult now I think, to find those public spaces, which used to be kind of reflected in the fact of the newspaper printout.

RICHARDS: What Calgary has lost—and I would say this about any city that is facing the slow dismantling of their major media outlets—is accurate, unbiased, careful, investigative journalism. And what that means is it is easier for people to get away with things.

STEWARD: The fact that so many people in Calgary read the Calgary Herald, there was more of a common understanding in the city about what was important, and what wasn’t. And I think the fact that the mayor’s office and the police and all these institutions also kind of worked with each other in that way—not that there weren’t disputes or anything, but there was just more of a sense of uniformity in the city about how things should proceed.

I think we’ve lost a public sphere, basically. We’ve lost a consensus approach to what’s real and what’s not.

FORD: There’s not enough of a cohort that is doing that, sort of to coalesce around a civic engagement in which we may disagree, but we talk to each other. Not past each other. Not around each other, and not against each other. But we all recognize that we are all citizens of a particular city, of a particular province, and that there must be some common consensus of what is important for the city, what is important for my life and your life. And we’ve lost that.

STEWARD: I think we do lose that sense of commonality, or that larger sense of community. And I think at times, that doesn’t really matter. But if you have a lot of things going on that are crucial, like for example, when we had the flood, you do need people to pull together. You don’t need fragmented voices at that point. People need to know what’s actually happening, and what they can do to make the situation better. And in a sense, I think that did happen at the time, but I think it shows how we lack that kind of community sense of who we are, and what we want to do together, when it’s so fragmented.

I don’t want my city, my society, to be so disconnected with each other — and it’s rapidly becoming so.

KLASZUS: Nearly six decades after she first walked into the Herald newsroom, Catherine Ford still writes an opinion column for the paper. She can’t help herself.

FORD: It breaks my heart that something that meant so much for so many years for so many people is reduced to a skeleton. One of the reasons that I agreed to go back writing for the Herald is because I think it’s important. I will believe that until my dying day. If I can contribute to people having a conversation—I mean, I don’t care, I literally do not care if you agree with me. I care that you think about things. That you think about the subjects that I have written about, or that other people have written about, and that it makes you stop and say, well, where do I stand on this point?

KLASZUS: As I interviewed Ford at her dining room table, she told me she doesn’t want to live in a world where everyone goes to their preferred echo chambers.

FORD: No, no, that’s just not the way I want my life to be. I don’t want my city, my society, to be so disconnected with each other—and it’s rapidly becoming so.

BRAGG: I think newspapers have become part of the past now. And I think it's historians who should be looking at it.

-30-

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl. If you value in-depth Calgary journalism, please pitch in to support it!

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!