Food banks have been around for almost four decades. Photo: iStock/lisegagne

Food banks: A band-aid solution to a growing problem

To address food insecurity, we need a radical change.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!

Food banks have been around for almost four decades. But depending on whom you ask, the anniversary is either the hallmark of an altruistic society or a gleaming red flag.

As we've come to know them, food banks solve food insecurity in the same way taking Advil remedies a headache. It might provide some temporary relief, but if your headache rages on, you'd probably make an appointment with your doctor to get to the bottom of it.

Even though food banks weren't established as a cure for hunger, the contemporary food bank model dulls the ache by filling in policy gaps.

Over time, the public has come to accept them as a permanent part of the social safety net. Today we're still swallowing handfuls of instant, short-term relief rather than asking why parts of our community are still in pain: Between 2017 and 2018, 518,600 people were food insecure in Alberta, according to Statistics Canada.

That's 12% of our province’s population.

Food banks solve food insecurity in the same way taking Advil remedies a headache.

What was intended as an emergency resource has become a permanent catch-all for food insecurity. Subsequently, policy-makers are off the hook for ensuring basic human needs are met.

The evolution of food banks

Philanthropy isn't a modern concept. Ancient Mediterranean societies celebrated acts of benevolence. Charity is among the core values of many religions, cultures and political philosophies. Giving is human nature.

"There are histories of sharing mentalities and 'How do you look after your neighbour' and all that kind of stuff throughout history," said James McAra, CEO of the Calgary Food Bank.

The first Canadian food bank was established in Edmonton in 1981 (or in Montreal, there's some disagreement over which came first). Members of different non-profits came together to address hunger and wasted food. It was founded as an emergency reaction—it caught families and individuals who fell through the cracks.

"At that point, it was an absolute necessity because of the fact that we didn't have any structures in place to help people get food to feed their families," said Kim Raine, distinguished professor at the University of Alberta's school of public health.

There are now over 700 food banks in Canada. Almost 150 operate in Alberta.

"We're coming up on 40 years next year," Raine said. "If we still have food banks, it's not an emergency response."

I don’t think that it is realistic at this time to consider that food banks are temporary.

Over time, food banks evolved from a temporary solution, becoming the default answer to food insecurity in Canadian society.

"Most food banks consider themselves as a supplementary source, not a primary source of food," said Arianna Johnson, senior project manager for Alberta Food Banks.

"I don't think that it is realistic at this time to consider that food banks are temporary."

So, where did the expectation that these establishments were catch-all solutions come from?

A couple of places. For one, it feels good to give and have a sense of making a difference. Donating to the food bank offers a sense of tangible, traceable generosity.

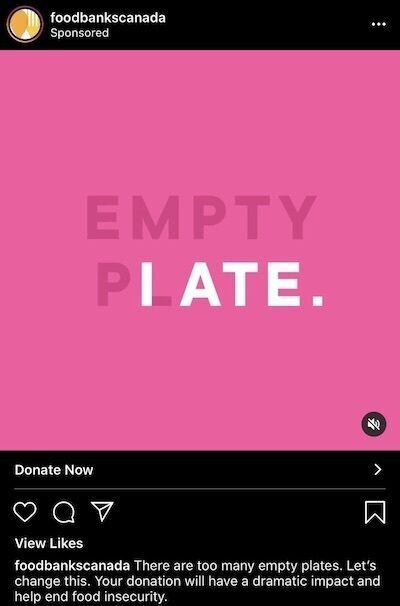

"There are too many empty plates," a Food Banks Canada Instagram advertisement reads. "Let's change this. Your donation will have a dramatic impact and help end food insecurity."

But donating to the food bank can overshadow questions about how significant our goodwill is—and the lasting impact of our donation.

And the Calgary Food Bank itself acknowledges the need for larger policy changes.

"Food insecurity is a symptom of something else—most notably income insecurity—and this is amplified in our current situation," McAra wrote in March, after the COVID-19 shutdown kicked in.

In 2015, McAra told CBC that ideally, Calgary should eliminate its food bank.

"I think Calgary should be the first community to close their food bank, to create a truly vibrant community where a food bank is not needed," he said at the time.

"At that point we write a book so we can share with everyone else how we managed to get rid of a food bank."

At bottom, food insecurity is symptomatic of poverty.

We know the root cause of food insecurity is a lack of income.

"Food banks never have and will never address food insecurity," said Lee Stevens, policy and research specialist at Vibrant Communities Calgary, an organization that works to reduce poverty in the city.

"We know that food insecurity is tied to financial security," Stevens said. "We know the root cause of food insecurity is a lack of income. And so this is something that we need to get into the public consciousness."

In 2019, the Calgary Food Bank distributed over 98,000 food hampers. In the same year, only 30% of its clients had employment income.

Working towards dignified supports

The Calgary Food Bank has also been criticized for requesting government ID from its clients.

"It is dehumanizing in a way," said Lourdes Juan, founder of two Calgary food-related non-profit organizations: Leftovers Foundation (a food rescue charity) and Fresh Routes (a not-for-profit mobile grocery store that brings fresh food to neighbourhoods facing barriers). Both operate without asking for ID or personal financial information.

"If you think of when you and I go to the grocery store, we don't get asked for government ID or for proof of our income to buy what we need to buy," Juan said. "And that's what we're asking when we don't have a food dignified model."

Food dignity is the bedrock of most food bank critique.

It can be degrading to have to ask for charity for one of our most basic needs.

Food dignified models work to avoid perpetuating social stigmas tied to being on the receiving end of charity. They try to move away from making their clients feel less-than or "needy."

"It can be degrading to have to ask for charity for one of our most basic needs," Raine said.

McAra says the food bank requests ID as the organization struggles to control demand.

"Unfortunately, there are jerks out there who will take seven apples when they're second in line, leaving the 15 people behind them the choice of only two apples," McAra noted. "We have to have some way to actually ensure that everybody gets food."

Other projects have taken a different approach. The Calgary Community Fridge is a new project in Crescent Heights. It's maintained by Alice Lam, the project's co-founder, and the residents of Crescent Heights. People can leave and take what they want in this fridge—no strings attached.

"We're really taking a non-judgmental lens with this fridge," Lam said. "Even if it gets emptied out by one person, we're trained not to judge. We don't know if that person's bringing it back for their entire apartment complex, for their family, for their neighbours."

Paul Hughes, the founder of Grow Calgary—an urban community farm—has been fighting for food dignity in the city for years. He says that whether or not collecting personal information deters "abuse of the system," it still has an impact on Calgary Food Bank clients.

"I've lived in poverty and I've had to deal with [the food bank]," Hughes said. "I've dealt with hundreds of other people who have had to go through that process. And it's what I call 'soul sucking.' It's not friendly. It's not nice going into that lineup and being like cattle."

Managing resources also means managing who gets food and how much. The Calgary Food Bank has a flexible income threshold to accommodate all households in need. Additionally, there is a soft limit of seven hampers per household per year.

"This is for a crisis," McAra said about using the food bank. "This is for individuals who have a need, and we want to make sure our resources are focused in the right area."

There’s a widespread assumption that if governments don’t ensure their citizens’ needs are met, the food bank will step in.

But society doesn't necessarily view food banks through a "crisis" lens. There's a widespread assumption that if governments don't ensure their citizens' needs are met, the food bank will step in.

Those needs are not optional—yet food is often treated as secondary.

"People think about food as being one of those discretionary items," Raine said. "So, you know, pay your rent and then go for charity to a food bank. That's so demeaning. The dignity is just taken out of that experience of having to ask for one of life's most basic needs."

"Instead of ensuring that we have adequate minimum wage, that social assistance rates are adequate to cover the cost of healthy living, that unemployment insurance is adequate to cover the cost of living—food banks become a way to take that responsibility off because people have that option of getting food by charity," she added.

‘We need a radical change’

Nearly everyone I spoke to for this article said that universal basic income (UBI) is the solution. It allows people to purchase what they need and addresses issues around dignity.

"The current income support system that we have in place is not working and that's also costing us millions of dollars," Stevens said. "I don't know if it's ever worked. So we need a radical change anyway."

The current income support system that we have in place is not working.

When the federal government introduced the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) in March, Juan says that Fresh Routes saw less demand. That was also the case for the Calgary Food Bank for a few months.

It seems cut-and-dried: Give the people money, and they'll spend it on their needs. That can come in the form of a universal basic income, an increase in Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH), sustainable food costs, affordable housing—the list goes on.

In September, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney said the UCP is re-evaluating the qualification criteria for AISH in search of provincial cost-saving.

"Nobody knows what's happening with AISH," said Mark Shaw, who mostly relies on AISH for his income. "People are very, very concerned that they're going to be cut from that. So if I have to sporadically go to the food bank already and if they cut AISH... what's the future going to look like for me?"

Hughes explained that the infrastructure is already in place for the move towards universal basic income, so the idea isn't as far-fetched as it may sound.

"We just have to reallocate the resources," he said. "Tax dollars are already going towards income support and AISH—we've already almost built it."

"It's the only thing that UBI 'house' needs now, as it's got everything else."

Hadeel Abdel-Nabi is a regular contributor to The Sprawl. Her work has also been published in VICE, Avenue Calgary, HuffPost and elsewhere.

CORRECTION 11/12/2020: We originally misidentified Lee Stevens's title as community and engagement specialist at Vibrant Communities Calgary. Her title is policy and research specialist. The Sprawl regrets the errors.

We want to hear from you! Send letters to the editor to hello@sprawlcalgary.com.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!