Sprawlcast Ep 4: The Streetcar that Wasn’t

A century later, International Ave is finally getting decent transit.

We’ve started going the extra mile with our Sprawlcasts and providing a full transcript, which you can find below—along with old newspaper ads, renderings and other goodies.

[SPRAWLCAST THEME]

JEREMY: You’re listening to Sprawlcast. It’s a collaboration between the Sprawl and CJSW 90.9 FM, and we are broadcasting in Calgary on Treaty 7 land. My name is Jeremy Klaszus and I’m the founder and editor of the Sprawl, and at the Sprawl we do journalism a little bit differently. We do depth, not breadth. Context, not clickbait. And we are constructive, not cynical.

I’m really excited to bring you our fourth episode: The Streetcar that Wasn’t.

JEREMY: This is the sound of 17th Ave SE, also known as International Avenue. As you can hear, that’s no streetcar. Those are cars, trucks, buses. And we’ll get into why that is. But first we’re going to pop into a strip mall along the street here. We’re going to go into Green Cedars Food Mart.

MIKE SAROUT: The best way to explain the shop, honestly, is if you’re online and you see a recipe and you’re like “what the hell is that?” You’re more than likely going to find it here. And if you like hummous, you’ve gotta try our hummous. We made top 5 foods in Canada — we were on CBC I think it was a few years back, as one of the top 5 foods in Canada.

So if you really like hummous and you’re listening out there, we’re going to ruin it for you.

JEREMY: This is Mike Sarout and his family owns and runs this shop. They have for 18 years. And seriously, the hummous is the creamiest, smoothest hummous I’ve ever had. I bought a tub from him and basically finished it that night.

This is what International Avenue is. A diverse street where you have hundreds of little shops and restaurants like this one.

MIKE: I wouldn’t just say one word, as in culture, because Canadians in general — different backgrounds, right? But the amount of different backgrounds that are available on 17th Avenue — anything you’re craving, you’ll find. From shawarmas to Ethiopian restaurants to a shisha lounge. Whatever you’re looking for. McDonald’s, Tim Hortons, it’s all here.

And it’s really centralized when you come to location. Downtown is five minutes away. You’ve got 16th Avenue, Memorial, Stoney Trail — it’s all so close and accessible.

JEREMY: It’s about to become even more accessible. That’s because International Avenue is undergoing a huge transformation this summer. If you listened to our last episode about 17th Avenue SW, you know that what’s happening there is basically a facelift — some minor cosmetic improvements. That’s not what’s happening on 17th Ave SE.

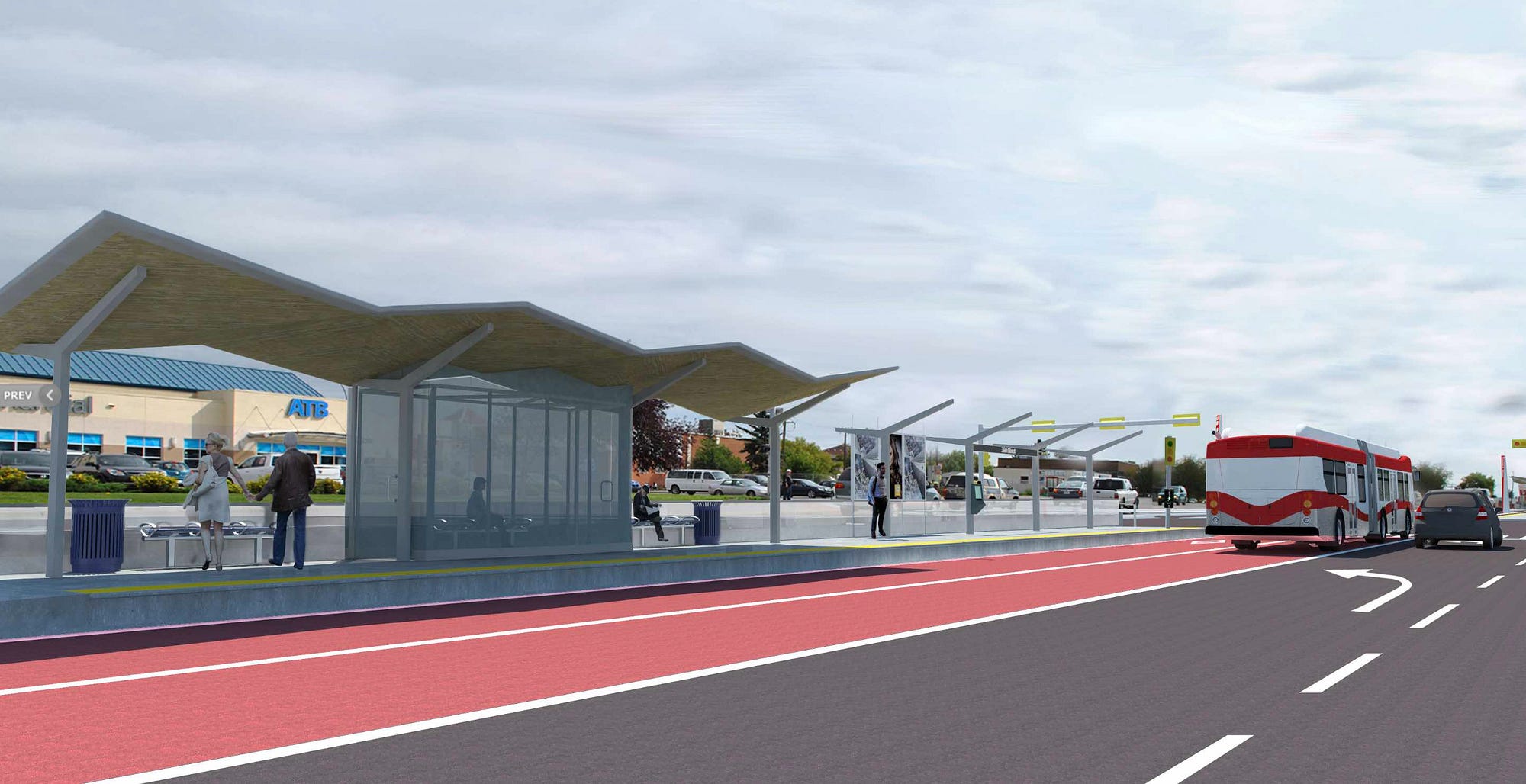

It’s a $180M revamp and it’s substantial. New dedicated BRT bus lanes are being built right down the centre of the street. And new bridges for these buses are being built over Deerfoot Trail and the Bow River. This is a big deal, because this area of the city has been disconnected for a long time — and the project that’s happening now has been decades in the making.

‘The infrastructure was so sub-standard’

ALISON KARIM-MCSWINEY: I remember driving through with my sister when I was fairly young. I remember she was going to International Stereo to buy a stereo. And I just remember looking around and saying — I didn’t feel safe. And the reason why I didn’t feel safe is because of the way it looked.

The infrastructure was so sub-standard. It just was a different world when you came over Deerfoot.

JEREMY: This is Alison Karim-McSwiney and she’s been leading the International Avenue BRZ, or business revitalization zone, since the early ’90s. And she’s really been driving the vision for the avenue ever since. Here, she’s reflecting on her early impressions of the street before she got the job.

The infrastructure was so sub-standard. It just was a different world when you came over Deerfoot.

ALISON: And I thought — yeah, it’s not really fair. Why is it so different from other parts of the city? Why is the road all crumbly? Why is there chipped sidewalks? Why is there no handicapped accessibility? All those kind of things. It really stuck in my mind.

JEREMY: Soon as Alison was hired, she didn’t waste any time in trying to make the street better.

ALISON: We did a whole redesign plan of the street and we took it to the city. We had some good research that said I think 40% of our users were not auto-oriented. I think 28% were walking, 10% transit and 2% were cycling. So from that, we actually did a whole redesign plan. And it was quite pretty. We had sidewalks. We had delineated crosswalks that made it safer.

It was such a wide street and so poorly planned that it really wasn’t safe to cross. So what we were finding was there was no movement from north to south as readily as it could have been. So if you were living on the south side of the street, you often didn’t want to go to the north side because you had to cross this massive, unsafe roadway.

So we looked at how we could do things a lot different. We actually did traffic calming — which of course didn’t go over well with the transportation engineers at the city of Calgary. And we also had other things incorporated in — public site amenities, we had places for people to sit, we had art, all sorts of great things. And we paid for that ourselves.

We took it down to the city. This was like 1995. They pretty much said, “Well, that’s not going to happen.”

A car-centric thoroughfare

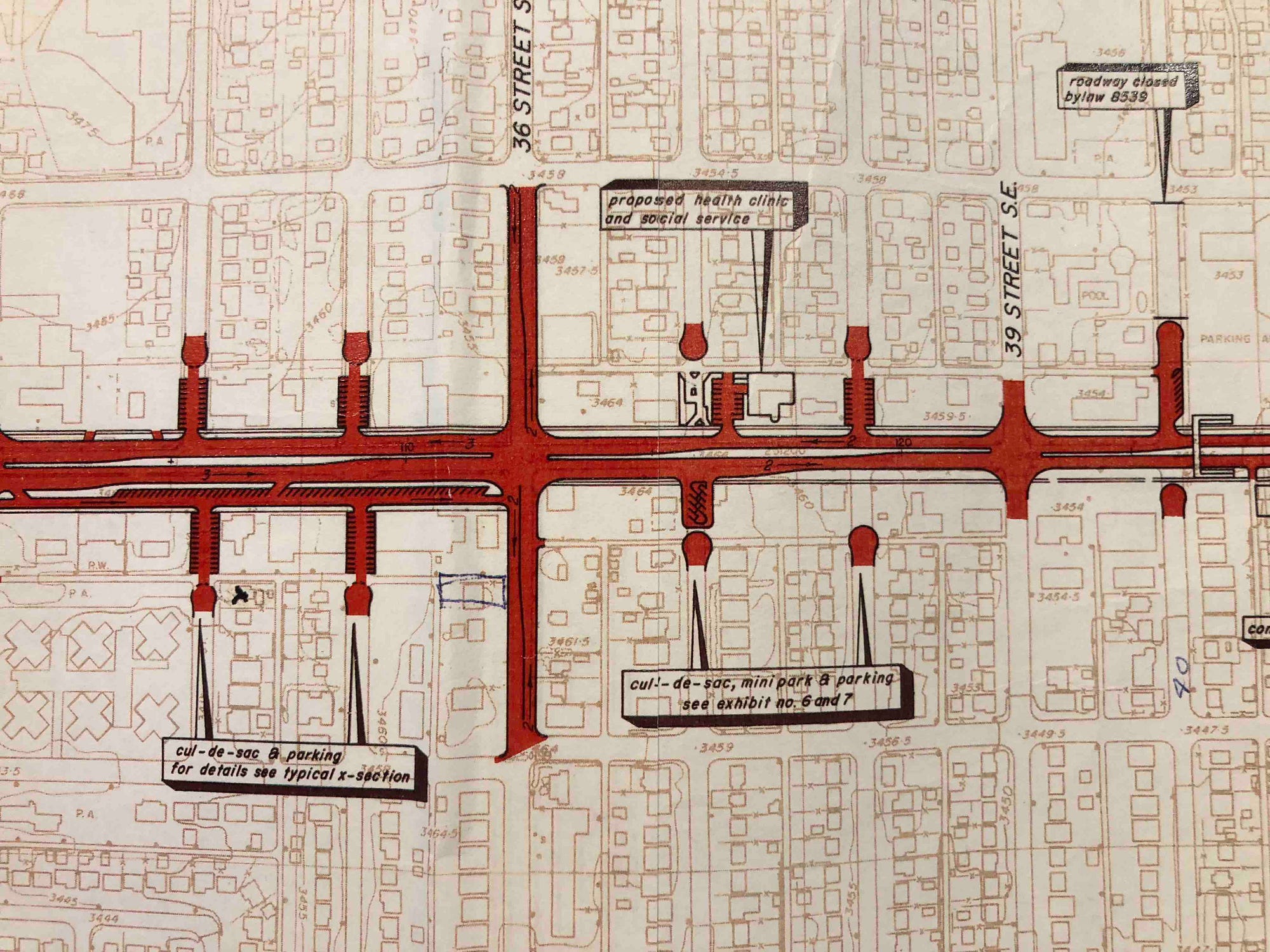

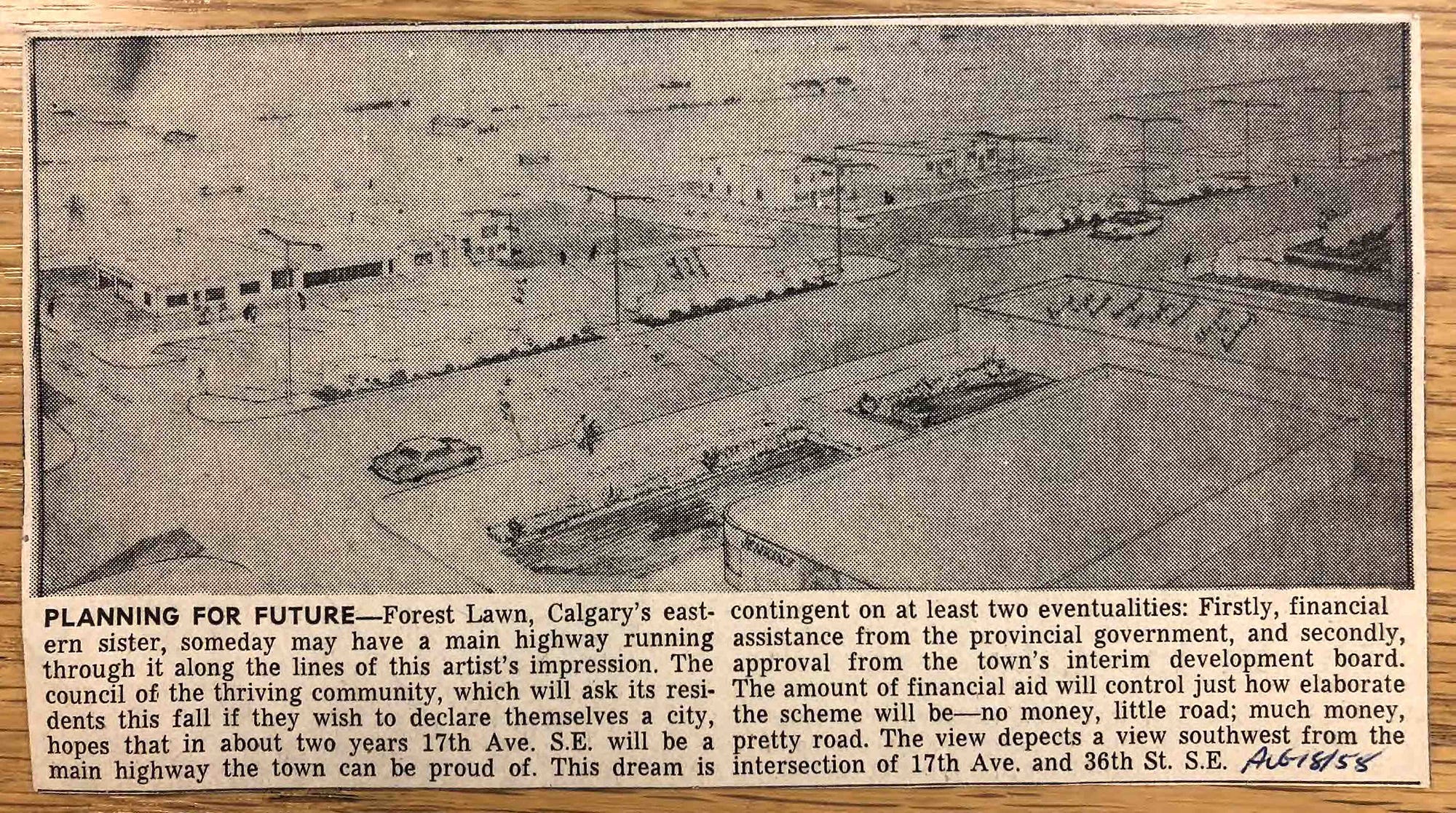

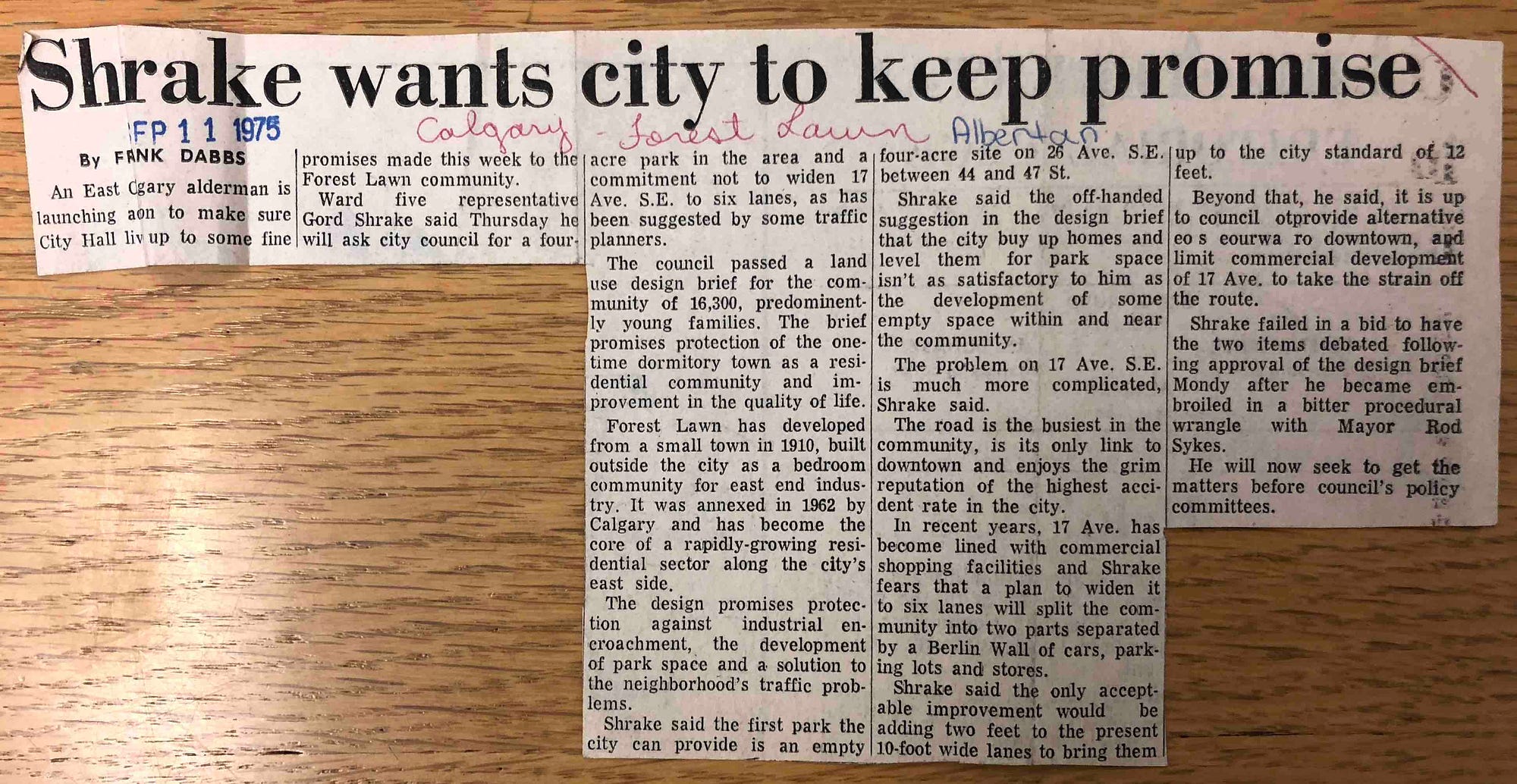

JEREMY: Alison kept running into a barrier at city hall. Here was the problem. The city’s vision for the street — or lack of vision — was guided by a planning document from the 1970s. And this plan called for the street to be widened. It was already a wide street to begin with but they wanted it to be widened further — basically to move more cars.

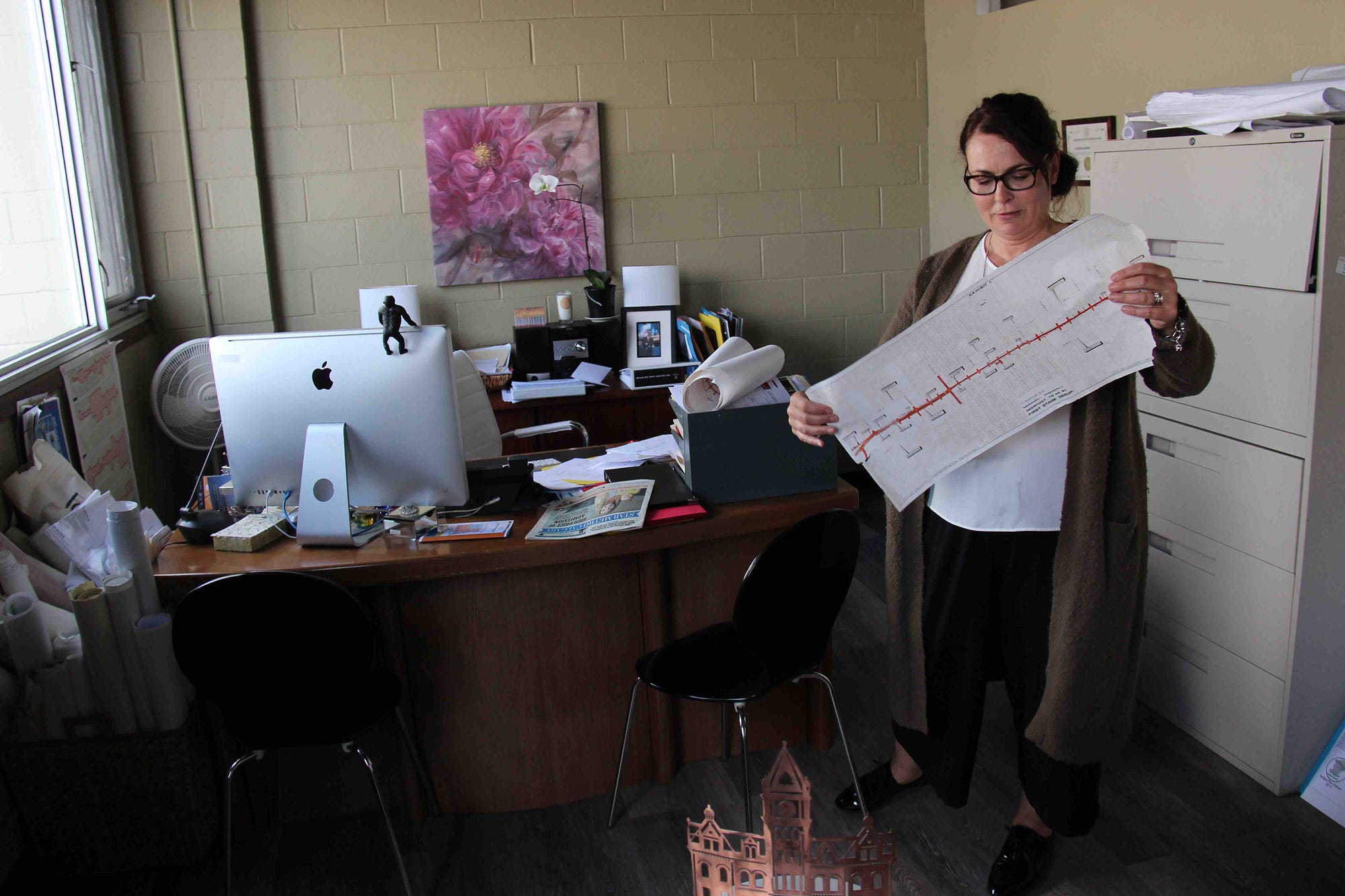

The plan also called for a series of permanent road closures on neighbourhood streets along 17th Ave. I wanted to dig into the archives to get more info on these historical plans. And when I asked the city about this, they actually directed me to Alison. Because she’s been keeping all these records in her office in a filing cabinet.

Her office is strewn with maps and old plans and blueprints and all manner of documents that have been accumulated over decades.

ALISON: Ok, so what are we looking at here. Oh! This is a good one. This is the overall map. This is the different phases of the CALTS survey that they did…

JEREMY: This is what year?

ALISON: This has always been on the books since 1976 for the area. It’s now actually been removed because there’s a brand new transportation plan that you see that’s ocurring now. But see all these? These little things are all road closures.

You note that there’s really not any landscaping, very little sidewalks — it’s all about moving vehicles. And that’s a real concern. If you actually count them, we came up with 26…

JEREMY: …26 of these road closures.

ALISON: Yeah, up and down the street.

JEREMY: So basically you wouldn’t be able to get onto 17th from the community.

ALISON: You pretty much couldn’t, no. So then you question: why is there even a business district if you’re doing that? You just want to be a roadway, and we never wanted that. Obviously we work for the businesses and for the community.

I think this was pretty much the motivator for the last 20 years. To make sure this plan was never implemented.

A transit-anchored multimodal boulevard

JEREMY: Even though this was the plan on the books, by the 1990s, people at city hall were starting to realize this makes no sense.

I’ll let Councillor Gian-Carlo Carra tell the story.

COUNCILLOR GIAN-CARLO CARRA: Dr. Paul Maas was hired by the City of Calgary, moved to Calgary and his research, getting his doctorate, was all about pedestrian areas and pedestrian use of main streets. And so he undertook sort of a review engagement of the kind of work he did for his doctoral dissertation in Calgary, in his new home, in his role as the city architect.

What he found was that on International Avenue, you had amongst the highest concentration of pedestrian-origin shoppers in the least pedestrian friendly environment. So people were walking from their homes to shop. People were walking from their homes and taking transit — using the avenue as a pedestrian oriented main street in a much higher per capita sense than the other traditional main streets in the city, most people arriving at those by car.

On International Avenue, you had amongst the highest concentration of pedestrian-origin shoppers in the least pedestrian friendly environment.

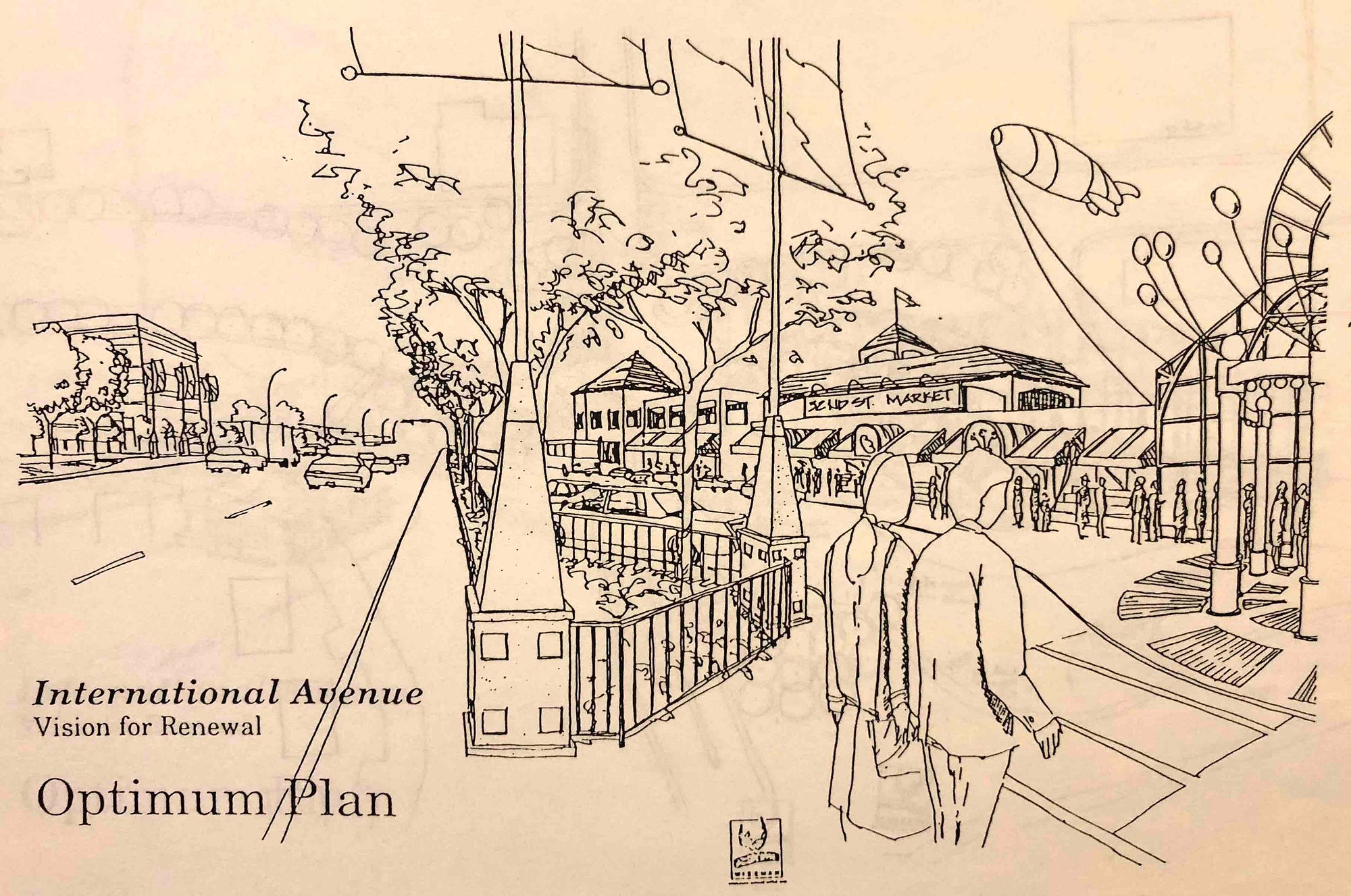

JEREMY: Councillor Carra was elected in 2010. But before that he was involved in a project called the International Avenue Design Initiative. This is a project that started in 2003—basically to reimagine this street. There were people from the City of Calgary involved, the BRZ was involved and the University of Calgary also played a big role. In fact, the university actually ran a course about this and Carra did his master’s thesis on this project. And some really important work came out of this design initiative.

CARRA: Anywere you go in Calgary the population on the ground does not reflect the ethnic diversity of our city writ large—except along International Avenue and the communities of greater Forest Lawn. In those communities, between Memorial Drive on the north, Peigan Trail on the south, from the Bow River escarpment to the ring road, you actually have a population that reflects the population writ large of the city.

It really is an International Avenue and it’s an international set of communities. And its main street should be a great street. That’s one of the arguments we made.

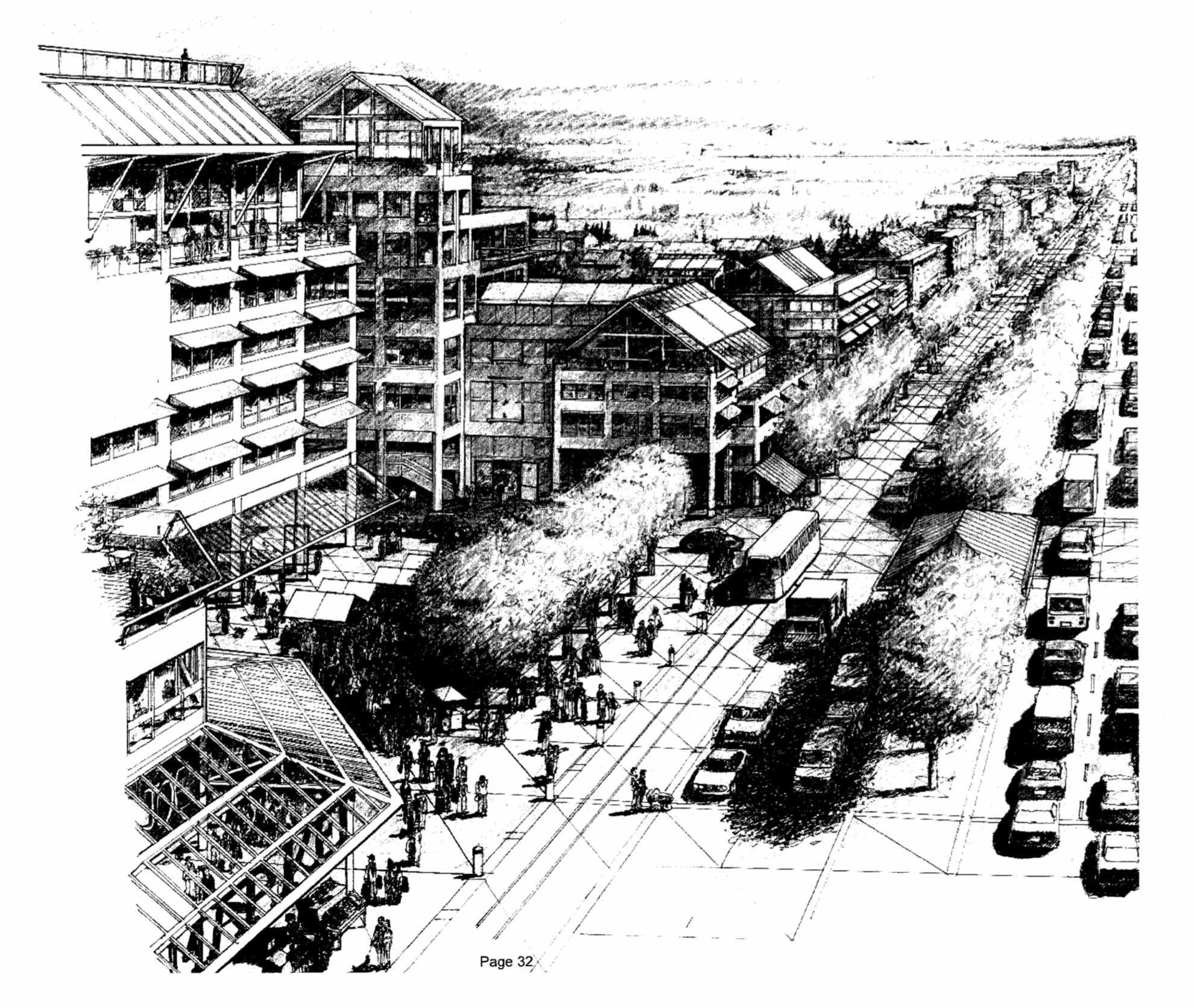

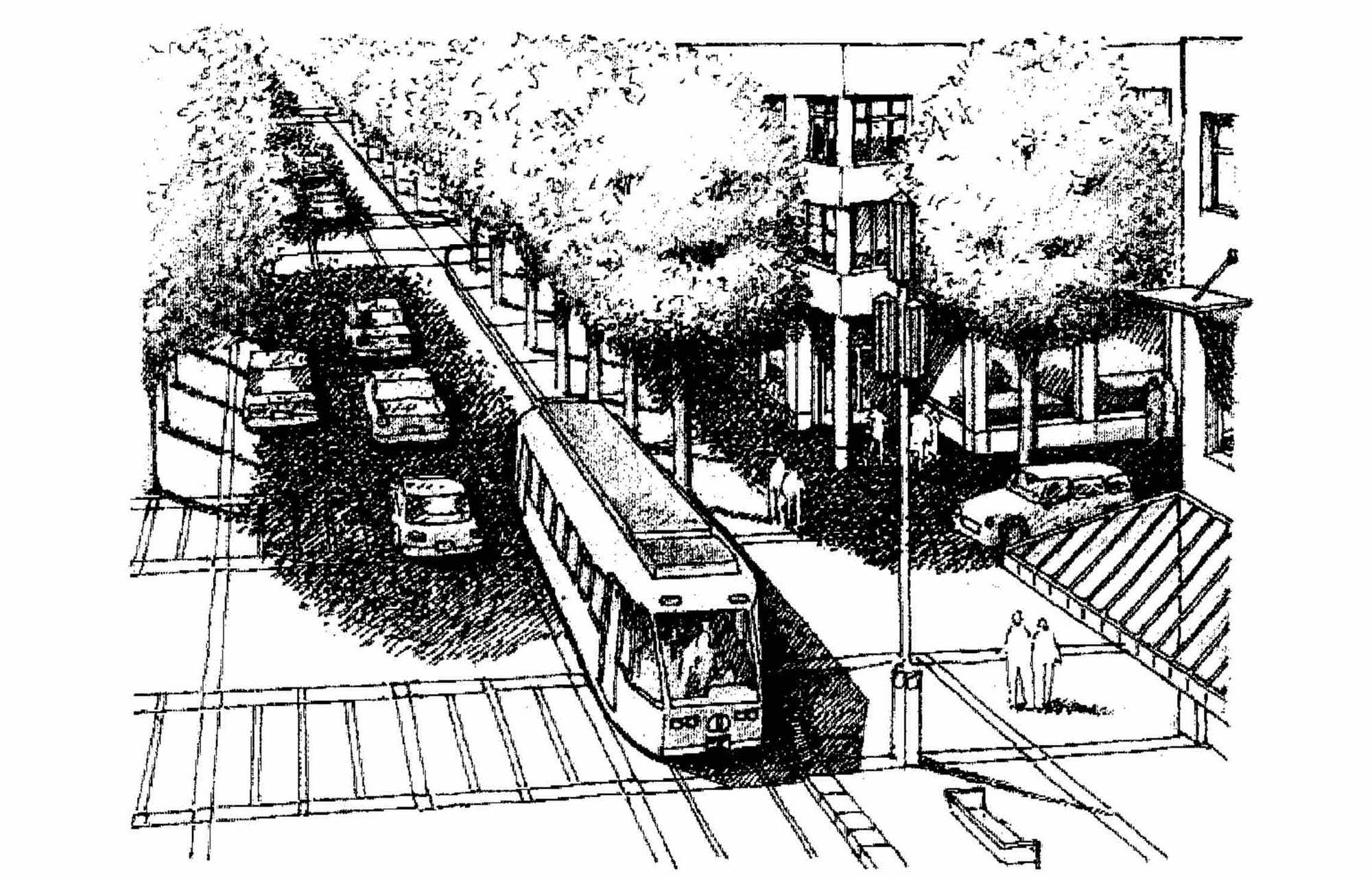

We envisioned a multimodal, multiway boulevard anchored by transit, putting the forest back in Forest Lawn, wide sidewalks. And we drew a lot of pretty pictures and laid out some AutoCAD ideas about how that avenue would work.

JEREMY: And they developed a strategy for what they called the East Calgary Corridor, running from Calgary up International Avenue and all the way out to Chestermere.

CARRA: You had a relatively short corridor that had great bones, and that had great population. And the idea was that if you ran great transit out along there, you would solve the original sin that had plagued the town of Forest Lawn: that it was completely disconnected.

JEREMY: The original sin. OK. Now it’s time to talk about the streetcar that wasn’t.

Forest Lawn’s great streetcar swindle

To understand what’s happening on International Avenue today, we have to go back just a little over a century to 1910.

CARRA: Forest Lawn was a town out on the eastern edge of the city. And basically it was a lower income town because it was a bit of a bedroom community for people who worked in Calgary but couldn’t afford to live in Calgary.

JEREMY: I wanted to find out how the town got started. So I went to the local history room of the Calgary library. And there I dug through a bunch of newspaper clippings until I found it — or thought I found it.

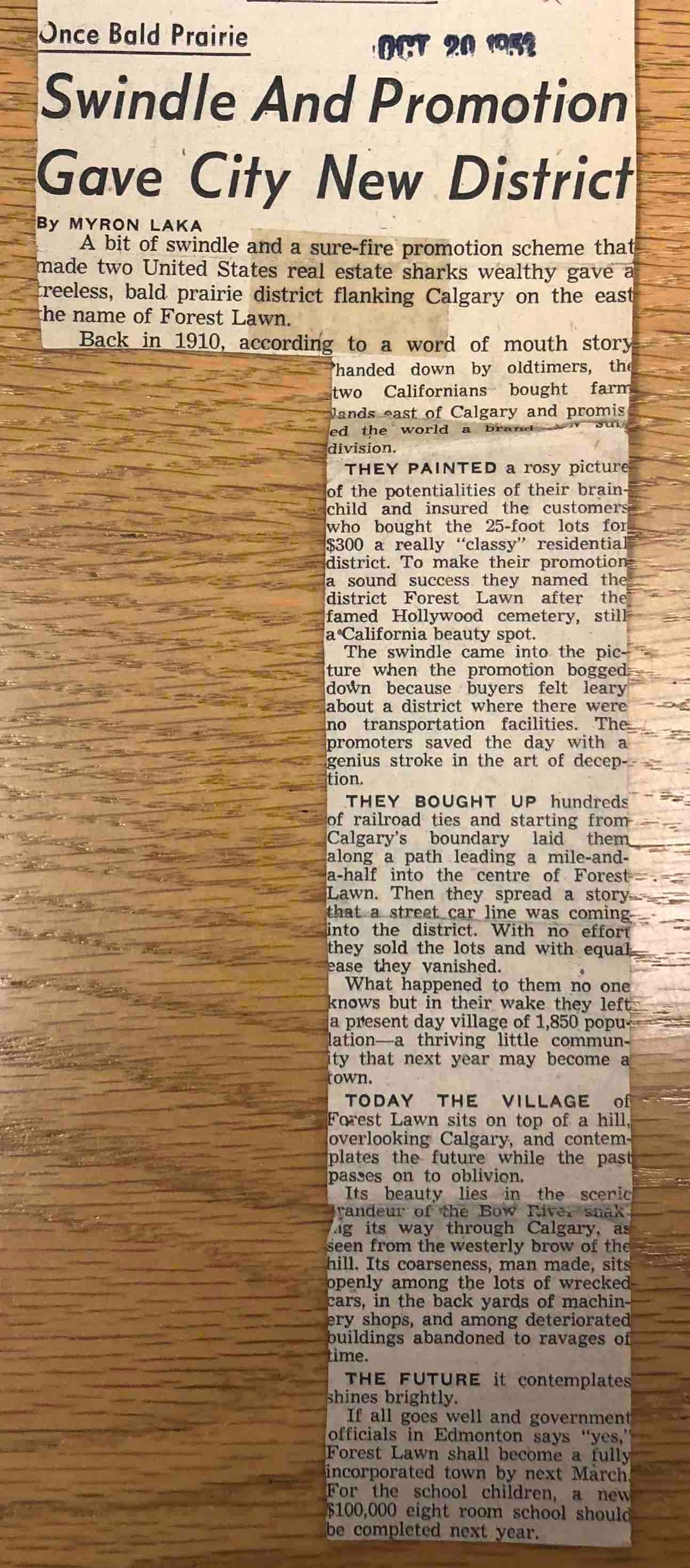

Here’s the story that’s been circulating for a while. A couple of American real estate men bought farmland east of Calgary for a new subdivision. They called it Forest Lawn, naming it after a picturesque Hollywood cemetery. But they had a problem. People weren’t buying the lots because there weren’t transportation facilities in the area. And Forest Lawn was separated from Calgary by the escarpment and the Bow River.

So how do you sell these lots?

As the story goes, these real estate con men came up with a stroke of genius. They said a streetcar line is coming into the neighbourhood. And they went as far as to buy up hundreds of railroad ties and they laid them from the middle of Forest Lawn down to Calgary. Their ploy worked. People were excited about the streetcar and bought the lots. But then the swindlers disappeared — and there was no streetcar.

I thought that was the story — but it turns out it’s a bit of a tall tale.

I thought I would double check by looking at old newspapers from 1910 and 1911. You can actually pull them up on Google’s newspaper archive. And I thought it would be cool to get one of those Forest Lawn advertisements from those days.

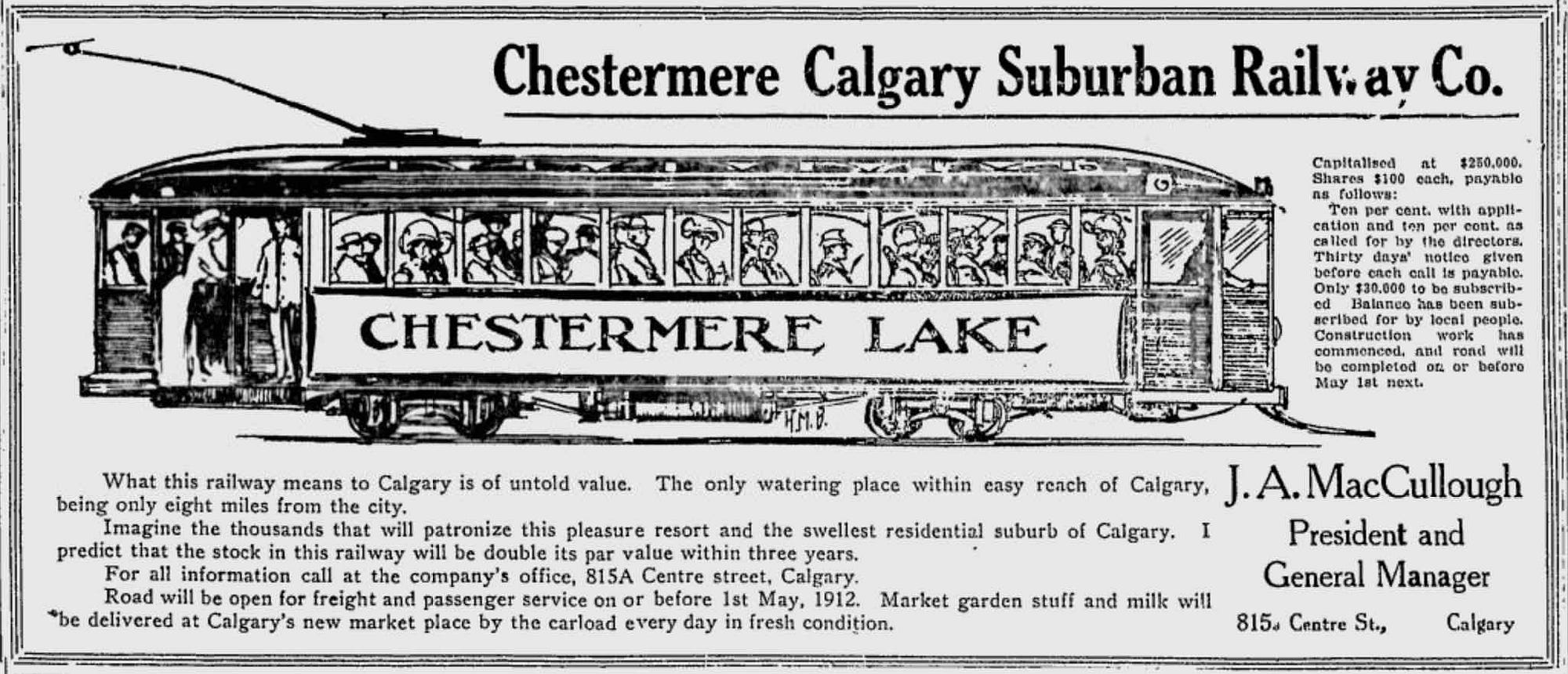

I couldn’t find one, but what I did find was advertisements for the Chestermere Calgary Suburban Railway Company. Calgary was about to undergo a streetcar boom — and this company planned to run rails from Calgary all the way out to Lake Chestermere.

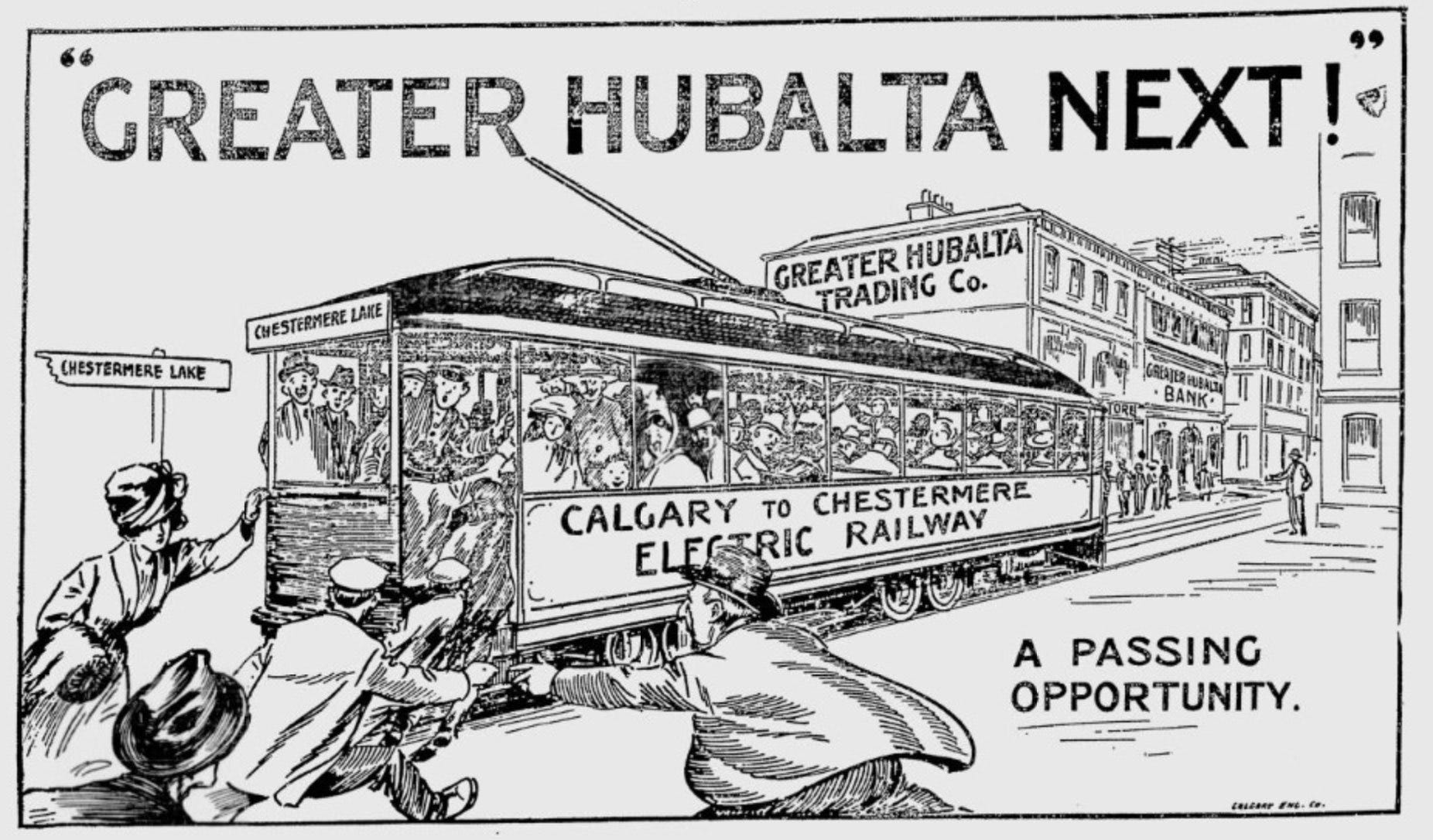

And it wasn’t just the Forest Lawn real estate people who were using this to sell lots. A bunch of subdivisions east of Calgary were doing the same. For example, Hubalta. And that’s how you got your subdivision going in those days. If there was a streetcar coming, it would draw the people.

But unfortuantely, the Chestermere Calgary Suburban Railway Company failed. The streetcar was a hope and nothing more. Forest Lawn was stuck with a disconnected community.

“Town of the future!”

CARRA: The act of commuting, at that time, at the turn of the last century, involved basically walking across the prairie to the edge of the escarpment, walking down the escarpment, crossing the irrigation canal, crossing the flood plain, crossing the Bow River and walking into Inglewood where you would catch the trolley to points distant.

It was considered at the time a very ethnically diverse place, in the sense that there were Polish people and British people and Ukrainian people all living cheek to jowl. And that group of people were the old town stock. There’s an interesting picture in my master’s thesis. I think the winning float in the 1958 Stampede Parade was the entry from the town of Forest Lawn. And it was a float entitled, Forest Lawn: Town of the Future. So there was a tremendous amount of civic pride.

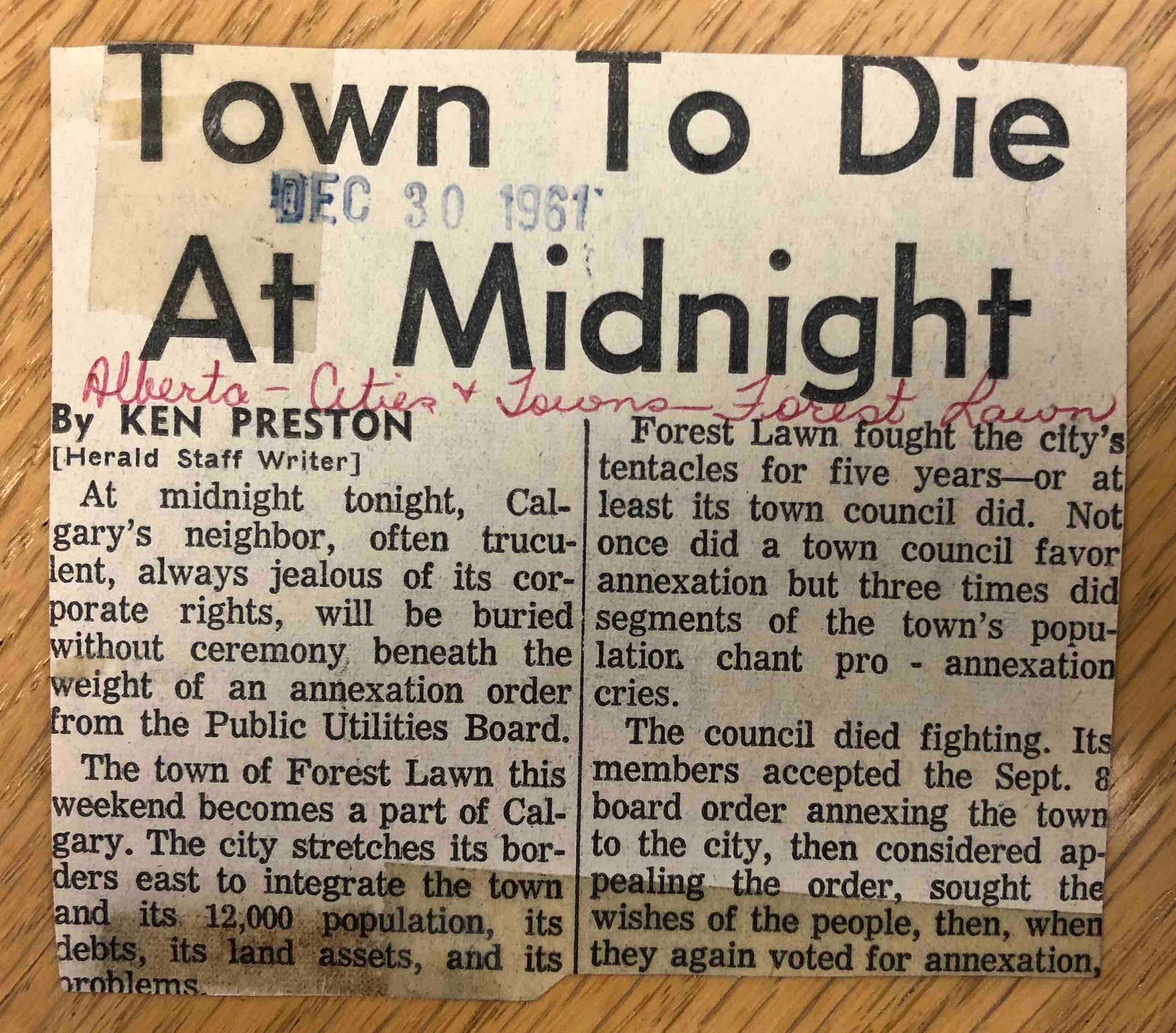

Mayor Akkerman was I think the last mayor of Forest Lawn. But by 1961, the realization had set in amongst the town folk that if they wanted to become that town of the future—if they wanted their roads paved, if they wanted to get off the septic system and onto a modern sewage system—annexation by the city was probably the thing that needed to happen. And so in 1961, Forest Lawn, the town, was annexed into the city of Calgary.

JEREMY: But once again, it was a let down. It was kind of like the streetcar all over again.

CARRA: Things didn’t exactly go as planned. It did not become the town of the future. They did get the roads paved to a certain extent. They did get off the septic systems, onto the sewage, but the city at that time built Deerfoot Trail, which added just one more barrier between it and the city. And the main street became a stripified, 1960s strip with giant parking lots.

A Berlin Wall of cars and parking lots

JEREMY: The people of Forest Lawn were stuck fighting for amenities and infrastructure that the rest of the city got. And by the 1970s, 17th Ave was a mess. It had the highest accident rate in the city—and meanwhile the city came up with its plan to widen the street to six lanes, making it basically a busier thoroughfare. And locals rose up against it.

The alderman at the time, Gord Shrake, warned that if this went ahead, it would split the community in two — and these two halves would be separated by a Berlin Wall of cars and parking lots.

By the time Alison was there in the 90s, the city still had little to give to the communities along International Avenue. And the community’s 1995 plan to revamp the street, and give it a decent public realm, just didn’t compute.

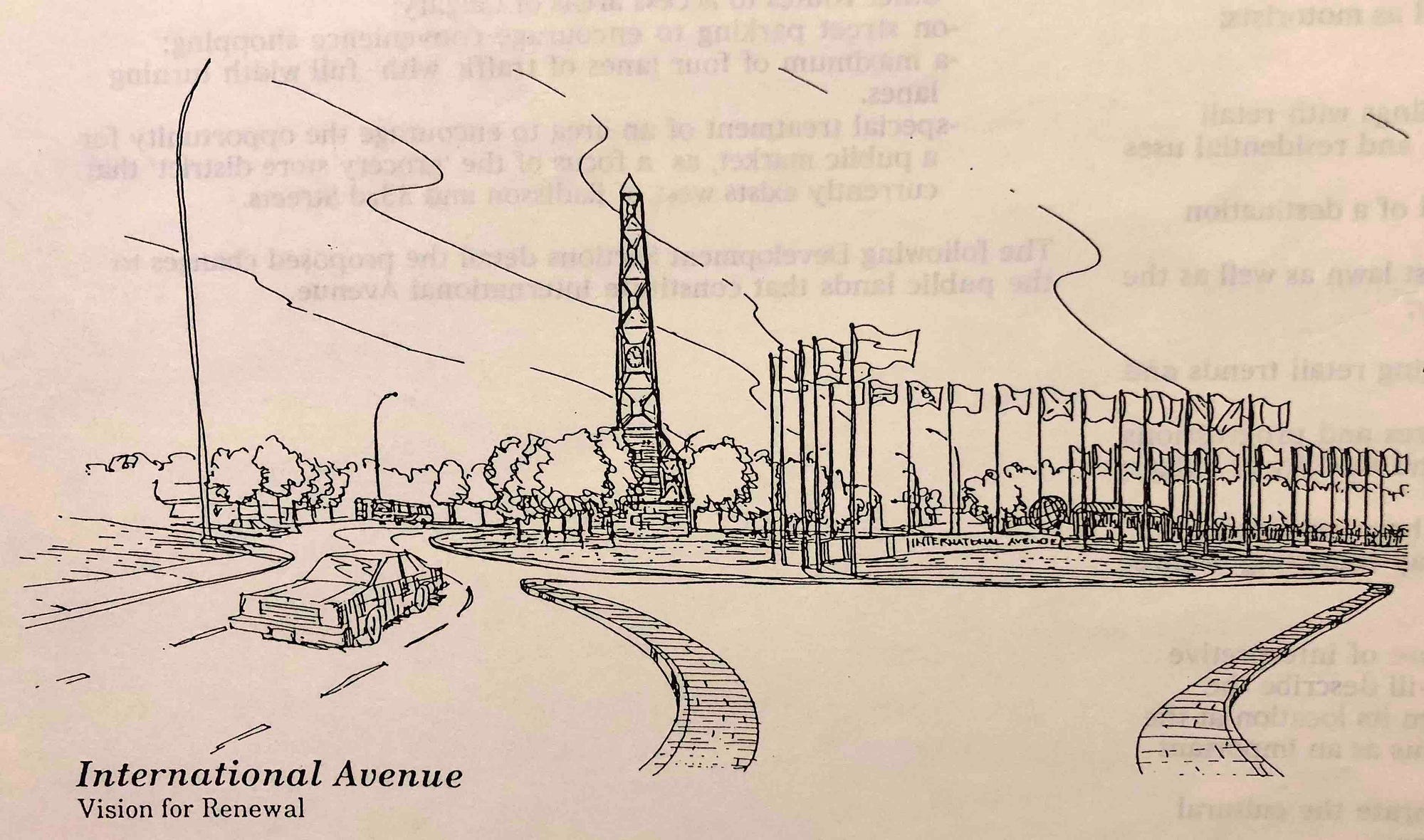

ALISON: This was extremely controversial. It was called All Nations Park and it was kind of set in the middle of the huge width that the city wanted. And of course, we’d get people saying ‘ok, you’re going to have kids playing in the park?’ Yes—but it doesn’t mean they’re going to run out onto the street. You’re slowing down the traffic. You’re creating a nice area for people to meander and to look.

JEREMY: After years of neglect, they also wanted to make a statement.

ALISON: We had quite a grand entrance. We had something that was fairly iconic, a gateway—which we’ll now be doing here. We also had boulevard trees, we had flagpoles, trash receptacles, decorative railings . We had three-metre coloured concrete sidewalks. Ten feet — which is actually happening now.

JEREMY: But even by the early 2000s, city hall wasn’t there yet. They approached streets more or less the way they always had.

CARRA: At the very same time that we were doing the International Avenue Design Initiative as a community-requested, university-led research project, the city was redoing 16 Avenue N as a transportation department-driven, community-resisted project.

Whereas we were envisioning a multimodal avenue they were envisioning creating a bigger, scarier car street. And it took the leadership, at the time, of my colleague now — Druh Farrell — saying, you know, this is old school, even for now, 2004. It’s time to think about other things than just moving cars.

We have to think about creating a great street. We have to think about how pedestrians move, all of those things. She dragged, kicking and screaming, administration into thinking about this as more than a transportation project. We were doing a community building project with the idea of a better street coming out of that. So it’s a very interesting tale of two avenues that was unfolding at the time.

Streetcar redux

JEREMY: In a blast from the past, the International Avenue Design Initiative proposed a streetcar for the avenue. This was nearly a century after a streetcar had been proposed in the first place. And the idea, once again, was to get decent transit out there.

So that 2005 plan had some pretty big ideas.

ALISON: That really helped in terms of helping to solidify what the community’s vision was. And from there, the city looked at all the different documents and tried to essentially — they couldn’t accept our document outright, the IADI document. They had to do their own research. Unfortunately it took about 4 to 5 years. It was quite a long time.

CARRA: There was a lot of churn in between 2005 and 2010, when I finally said “I can’ts takes it no more!” and became a city councillor. And very happily, when I was elected in 2010, we had a large contingent of strong east Calgary sympathetic councillors for the first time ever. And an east Calgary mayor. And Mayor Nenshi actually was very aware of the work we were doing, because he had sat on the granting committee for the Calgary Foundation that we had gone begging to for funds to help support this work.

JEREMY: By 2010, the city had finally come up with a new plan for International Avenue.

BRT to ‘make this street what it needs to be’

ALISON: They did come up with a great document, the Southeast 17 plan. The thing about that however was it was non-statutory. Which really didn’t help us a lot, meaning we still had a lot of inconsistencies. Because we had so many different communities bordering, we had different area redevelopment plans.

And so, for instance, we could block certain things like pawn shops in a certain area — but they literally could move just outside the 12 block radius and then they were allowed and there was nothing we could do. So there were a number of these things that really didn’t treat the street as a whole, which it needed to. And so just recently—this year we will have that plan actually made statutory. It means that the whole street will be consistent, which I think is huge.

JEREMY: It was also huge when the city broke ground on this new bus rapid transit project last May.

MAYOR NAHEED NENSHI: It’s going to provide efficient, reliable public transit within the communities of greater Forest Lawn and to get people downtown. Huge benefits for commuters all over the city. And it’s also going to make this street what it needs to be. Wider sidewalks, new boulevards, improved landscaping, safer crosswalks — a better environment for people to enjoy the wonderful businesses here.

JEREMY: That was Mayor Naheed Nenshi speaking at the groundbreaking ceremony last year. And get this. The public art for this project is being done by local artists. People with some sort of connection to the communities along International Avenue.

ALISON: The public art is going to be amazing. Along the BRT line, which is down the centre, it’s all ground level. It’ll be all glass, but there will also be a number of murals that are incorporated up and down the street and they’ll all be with the theme of food. So those have already been chosen. Tremendous quality of art. Very impressed.

JEREMY: Family businesses like Green Cedars Food Mart are happy to see this finally happening.

MIKE: If it’s going to bring more people to the area, that’s a bonus for any business that’s going to benefit from that. There are ups and downs obviously. Our plaza, you can see there’s lots of parking. We’ve got a nice big plaza. But I look at other plazas — there’s not too much parking close to them anymore. So there’s ups and downs to it for sure, but I’m sure they’ll address that when they come across it.

Cycle track got cut from avenue

JEREMY: This will be a new street. But not everybody is getting what they want.

CARRA: The big challenge of course is how do you make the avenue work for bikes? Because you’ve got to move traffic, you’ve got to move transit, you’ve got to move pedestrians on wider sidewalks.

You’ve got to create convenience parking to keep the businesses viable. It’s essential for a main street. If you’re driving by and you see a store, even if there isn’t room to park — that parking lets you know that you can get out. And it’s just absolutely essential to the psychology of successful retail to have the parking there.

And you’ve got to have enough width between the alley and what’s left to have viable buildings. And what got cut out on International Avenue was dedicated cycle track infrastructure. What we’ve done, is we’ve made the wide, wide sidewalks bylawed as multi-use pathways. So you’ll be allowed to cycle on them.

But the other thing that we’re doing that’s even more important is on 19th Avenue, with the savings — or with money from the general avenue fund — we’re working to build the first cycle track east of the Deerfoot. So International Avenue/17 Avenue SE is banded to the north by 16 Avenue and to the south by 19th Avenue. Both of these streets are really, really wide. Unfortunately wide, inappropriately wide. And largely backed on to by the back end of the businesses.

So the overall urban design plan is to front onto those streets and to narrow those streets and to calm them. And a cycle track’s a great strategy for doing that.

That will narrow 19th Avenue, make it a lot more pleasant, and it will act as a magnet, drawing all the cyclists who are commuting onto a cycle track. And 19th Avenue spits out right where the multiuse path of that transit bridge spits out onto the top of the escarpment. Between accommodating cycle commuters and accommodating cyclist patrons of the businesses, I think we’ve got it as great as you can get it.

JEREMY: It’s been over a hundred years since the people of Forest Lawn were first lured there with the promise of a streetcar. And now they’re finally about to get decent east-west connectivity.

I think we can all agree: it’s about time.

In a way, it’s like 1910 all over again, because once again there’s talk of rail transit in the future.

CARRA: Running down the middle of the avenue is a beautiful transit right-of-way that will run buses today, but is being designed so that we can lay track in the future. So $100M builds the avenue, $80M takes you down to Inglewood.

Over the next four years, my mission is to find another $80 to $100M to connect the Inglewood stop with a junction station on the Green Line. So at some point in the future, you’ll be leaving the downtown core on the Green Line. Or will you be on the Green Line? You’re either going to be on the Green Line or the Purple Line—and when you get to the junction station, you better be on the right train.

Because the Green Line is going into the southeast, and the Purple Line is heading out east, up International Avenue and out to Chestermere.

ALISON: That change has taken a long time and it’s taken a lot of perseverance. And I think what’s interesting is because the knowledge base has always been in this office, for a long time — for instance, I had a group who came through and they were planning on doing a redevelopment. And I looked at the plans and I said, why is there a road closure there on your plans? They said, that’s what the city told us. I said, that’s not right.

They said, well, we were told it was. And I said no, I can prove that it wasn’t right because I actually went to council and made sure that that was removed out of the document to make sure that that wouldn’t happen. But it still was on the city’s books.

So if there wasn’t a watchdog, all these things could be put in. But because we have evidence of everything that we’ve done since 1993, we have a really good historical archive that can pretty much pull anything up. And what was really funny about that was literally it took me I would say three minutes to find it. I’m like no, I remember this, and pulled it up right away and provided it, sent it to the city and said look guys, I don’t think that this is correct and they said oh my goodness, you’re right, absolutely.

CARRA: I have to give a huge shoutout. The BRZ has been led tirelessly through this entire period, and for many many years before I emerged on the scene, by Alison Karim-McSwiney who understood the avenue and the businesses she was working on and ran the BRZ not just as a business association, but also as a community development agency.

ALISON: There were so many things to overcome. And I don’t think that people realize all the policy and different things that had to change over the years in order to change the actual physical environment. And then you also have to convince people that it’s worthy of being changed, and that its time is due.

I have give kudos to our mayor and Councillor Carra and [former] Councillor Andre Chabot, particularly because they did really go to bat. They did like what they saw. We had a plan in 1995, and frankly if that plan would have been implemented, it would have been still in an amazing place. The 2005 plan with the International Avenue Design Initiative was an amazing plan.

But I have to say. I think the plan that’s being implemented now is the right plan.

CARRA: It felt like in 2004, 2005 when we were doing this work, people thought we were crazy people. But we had a lot of community support, we had a vision that is now not bleeding edge, but right in the wheelhouse of best practice. And to be in a position where the city is executing it is extremely exciting and extremely rewarding.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!