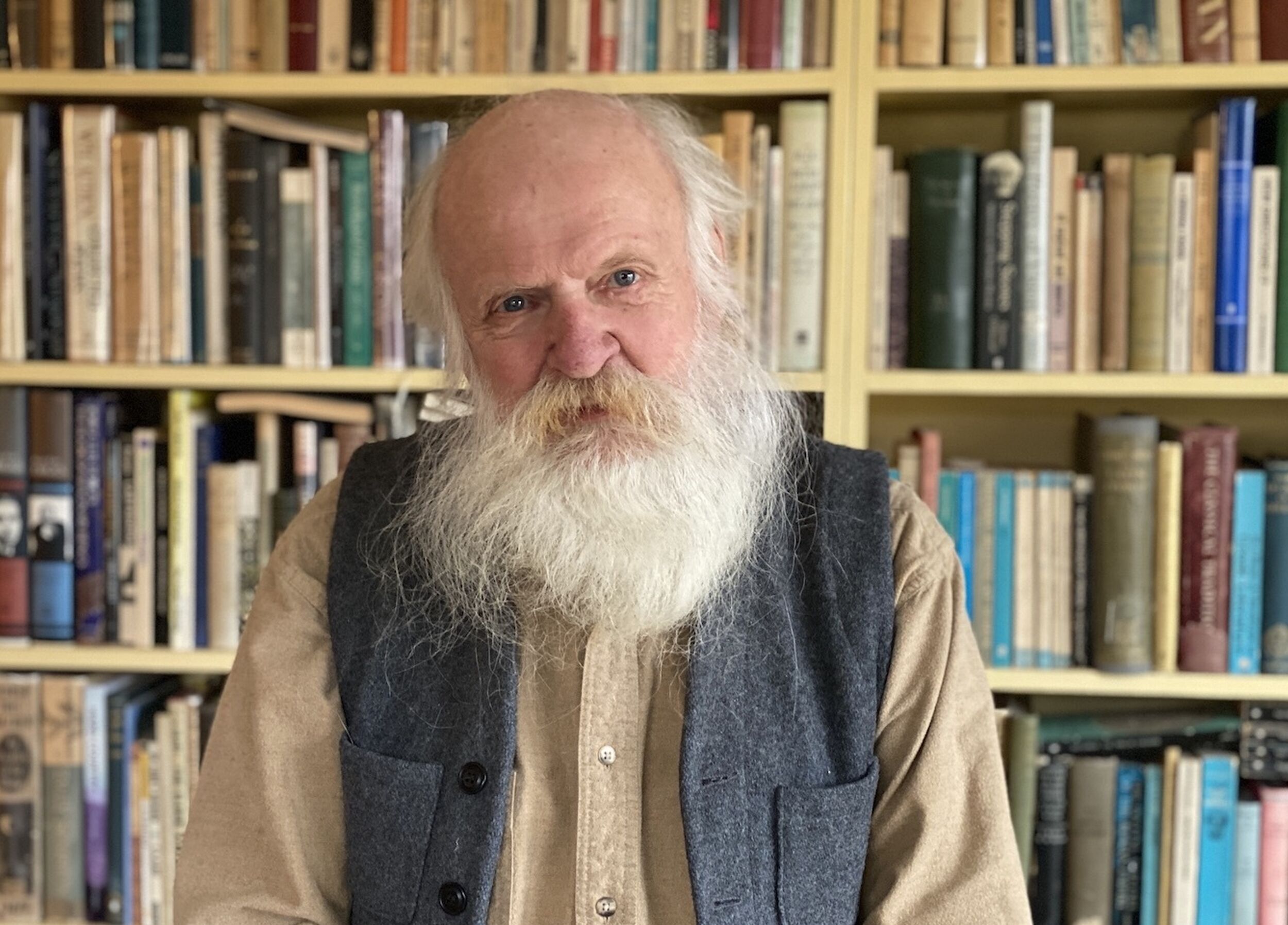

Photo: Jeremy Klaszus

Welcoming the stranger as an act of delight

When we do, says David Goa, something new is born.

Sprawlcast is a collaboration between The Sprawl and CJSW 90.9 FM. It's a show for curious Calgarians who want more than the daily news grind. Subscribe on iTunes, Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts. Thanks to our members, we also provide a written version of each episode for those who would rather read than listen.

Last week I spoke with Zakir Suleman about how living across difference can strengthen a neighbourhood and create places of belonging. For this Sprawlcast, I delved deeper into these themes with David Goa, a scholar of religion who lives in the in Old Strathcona neighbourhood of Edmonton.

He talks about the "spiritual disaster" of the suburbs—and the perils of homogenous neighbourhoods where we don't encounter people who are different from us or make room for the stranger.

In this edition of The Sprawl, we're exploring the theme of neighbourhood. How do we build meaningful connections in an urban landscape marked by disconnection? How can we be more present in our local worlds when the online world is always at hand—literally? And how do we remain open to the possibility of wonder and beauty outside our front door?

Goa has a keen interest in these questions. From 1973 to 2002, he was the curator of folklife at the provincial museum in Edmonton, where much of his work was with various religious communities throughout Alberta. After leaving the museum, he founded the Chester Ronning Centre for the Study of Religion and Public Life at the University of Alberta's Augustana Campus.

A few years ago I came across an interview with Goa and something he said really stayed with me. He was asked what his favourite tools are in his work, and this was his answer: "Story. Your story, my story, our story. Stories provide the way toward conviviality. In the presence of story, the world is made new because we are changed." As a journalist, that struck me so deeply.

I spoke with David Goa in his Edmonton home near the Mill Creek Ravine. This is an edited transcript of our conversation (you can hear more by listening to our conversation on Sprawlcast).

You moved from Camrose to Edmonton as a child. How did that change your understanding of neighbourhood?

We moved to Edmonton when I was seven. In Camrose, I think I witnessed, in retrospect, the last of what I would call "natural community." Camrose, as you know, is a small town, and it was smaller in the '50s. It had a substantial Norwegian Lutheran presence, which was my parents' tradition. So church, the main street, the people you might work for or the people that might work for you were largely known. And then there were Catholics. There were some Ukrainians. There were pious people and there were secular people.

I make a distinction between fraternity and community. Fraternities are like-minded people and communities always have difference in them. And I would also say communities always have things that you cannot know in them, but you have to encounter. Communities drink from the same wells. Everybody goes and draws water from the same well—metaphorically, anyways.

In small towns you potentially have a larger diversity than you do in Old Strathcona, my neighbourhood. Now, my neighbourhood is large, so it's not that there isn't diversity there. Of course there is. But your encountering of it is something you're going to have to work at. It's not going to be built into the structures of everyday life. Whereas in small towns and villages, in real neighbourhoods, it's part of how you walk the pathways. You meet the other, you meet strangers, you meet friends, you meet people you'd like to get to know.

I think in Camrose as a boy, the thickness of church, culture, and society are braided together in your daily life. That then is fractured when you come to Edmonton. We did feel a little bit like we were exiled, except probably my father, who loved the city, and who would get to know it immediately.

Because of my father's deep interest in engaging the other, we would do the family shopping on Saturdays downtown. And in Edmonton in the '50s—it was much smaller than now—I would say that every third person would nod at you at least, on Jasper Avenue, and you would always know a few people because Edmonton was still a kind of agricultural gathering place at that time.

I developed, I think because of those Saturday sojourns, a delight in the city, and a sense that meeting the stranger was always an opportunity. It was always a little bit like Abraham and Sarah who had perched their tent by the oaks of Mamre. The biblical account is that Abraham is standing in the door, in the flap of his tent, and he sees the three strangers. And that text is so beautiful. It says he runs out to them and he begs them, "Please don't pass by! My lords, please don't pass by."

When we meet strangers, it is often an annunciation. We will often hear a new word which will illuminate our life, illuminate relationships, illuminate the world.

So there's that tension which I think I sort of ingested rather early on. I was blessed to recognize, I think early on, that well-knit relationships were good and virtuous and they may be important as ground for meeting the stranger. But if you don't meet the stranger, those well-knit relationships are going to simply be what they are—become a bit ingrown, incestuous and not fruitful.

We will often hear a new word which will illuminate our life, illuminate relationships, illuminate the world.

One of the things we're looking at with The Sprawl is this fear that's in many of our communities, fear of the stranger. One story we're doing is about neighbourhood watch groups on social media. And how these things often play out is I see somebody out my window, I don't recognize them, and I assume they're up to something. And that seems at odds with what you're describing. I guess one of the questions is: how do we open that space within our neighbourhoods, those pathways?

Or: How have we come to this curious place? Because this is a curious place. It's not the way people normally lived in this part of the world. If you look at what has happened to Edmonton in terms of its suburban development as well as its land-based tax system—I'm not saying this is deliberate, but the implications of the way those two matters are structured are such that it creates economic ghettos.

You end up with people in a similar financial bracket in different places. And whether they are gated neighbourhoods or not—plenty of them are—they are gated mentally, and they are gated in terms of the financial capacity of the community. This is a disaster.

We know from the study of the development of suburbs over the last 70, 80 years, how this was engineered and what drove it. But it's clearly a disaster because it implies particular kinds of transportation systems.

And it's the spiritual disaster of it that I think is so significant. If you combine that kind of isolation with modern television and the internet, this makes it possible for people to live their whole life in a silo and to think that that silo is what is real and right and good and true and beautiful. That's a huge change in the spiritual landscape of human community.

It indicates a life which is compartmentalized around time and space, and around who is in and who is out. That, to my mind, is a tragedy.

The suburbs aren't the city. In Romanian, there's a word for this. I learned it from a Romanian scholar when I introduced her to Sherwood Park on a little research trip. She asked me, "What is this, David? What is this?" And we talked about it, and I tried to describe what it means to have this outlying area where the houses all look pretty similar and people make the same kind of income, and then they get in their car to go into the city to work. She talked about the urbanus—the urban world and what that really means. And then she talked about the paganus. She loved the paganus. This is the first time I realized what the word "pagan" meant. It means the wild places. And then she said, "Ah, this is neither the urbanus nor the paganus, and it's not the agricultural world. It is 'mahala.' It is nowhere."

This sounds harsh, I suppose. But it indicates a fragmented life. It indicates a dis-integrated life. It indicates a life which is compartmentalized around time and space, and around who is in and who is out. That, to my mind, is a tragedy.

In my neighbourhood here in Old Strathcona, I was on the planning committee about 45 years ago, when there were certain threats to the neighbourhood. One of our clear working principles of the committee was difference. But it took us time to get there; this required real argument. I made the case as best I could, and several others did too, that we wanted to live in a neighbourhood where not everybody looked like me or everybody lived like I did, but where there was room for those of a variety of economic means. Where there was room for the local house where children could reside whose parents no longer took care of them. Where there was room for immigrants. Where there's room for students. Where there was room for those that lived alone or couples and families as well.

Why? Because that's so much more a richer social texture, and it contains surprise in it. If you structure your life solely in a fraternal way, it really makes it very difficult for the new to present itself.

It's almost like this rediscovery of trying to learn about the person next door, or learn about my street. To reconnect to these things that are, in one sense, very immediate and very close by, and yet are very—

Hidden.

Hidden. That's a good word for it.

There's another aspect of neighbour that is striking to me. Neighbour is also someone who does not enchant you. The danger of likeness is the danger of always being enchanted by the mirror you see, enchanted by yourself. And in that sense, if you're always in a world of likeness, you can never have the stance of faith because faith is that disposition towards what is coming to greet you, which you do not know, and maybe never will understand. But it's a stance. It's the stance of Abraham and Sarah by the oaks of Mamre, to welcome the discovery of what you didn't know you knew.

That circumstance, as we know from the narrative, is that charming discovery that Sarah is pregnant. But whatever else it is, it is also a metaphor for the fact that through the encounter with the other, something new is born.

And that's always the case, even if the encounter is miniscule. If you're attentive, something new comes to be in that. That's one of the great gifts of the city, I think, and one of the great gifts of neighbourhood—if the neighbourhood is shaped so conviviality can exist. As opposed to shaping the neighbourhood so there can be no conviviality; there's only your way and your way is mirrored by your neighbour.

The danger of likeness is the danger of always being enchanted by the mirror you see, enchanted by yourself.

In Calgary, there's been research on how there are "three cities" in the city, and that neighbourhoods are increasingly sorted into areas of certain economic means. This isn't specific to Calgary of course—this is happening in cities across Canada. Yet often when we talk about "building community," we're talking about getting together with people who share an interest or are aligned around a certain ideal or whatever it might be. But what you're talking about—with your being on the planning committee almost 50 years ago—you're talking about community as something very different.

I think 50 years ago, we were trying to prevent something. We weren't trying to build something, and I'm curious whether one can actually build community. What we were trying to prevent was homogenization.

We were trying to prevent the planners, the developers, from making this a homogenous area based on their economic interests. So, in that sense, we were in a position of critiquing something and then trying to use the way in which properties are designated by the city as a way of ensuring that there would be diversity.

I think underlying a lot of what we're talking about—and not to get too broad about it—but in a lot of ways, it seems to me we are talking about the meaning of life. What is the purpose of our work, our families, our communities? Why are we here?

I think we need to interject into the curriculum and into the reading habits of adults, the rereading—if they haven't read it, or if they've read it before—of Leo Tolstoy's story "The Death of Ivan Ilyich," where you see a good person who did everything right and comes to the end of his life having done everything right, and it's empty. And the relationships have no surprise in them, and they really have no commitment in them, because there has not been communion. There has not been a coming together in delight around discovering another human being, not who they were but the wonder of the fact that they were.

We were trying to prevent the planners, the developers, from making this a homogenous area based on their economic interests.

I mean, I have a prejudice about this. I think we are made for communion. We're not made for some thing. And we're certainly not made to be consumers. But I've often thought for years that, to use a theological term, the doctrine of the human that we find in capitalism, and the doctrine of the human that we find in communism are in fact the same.

Both of these great economic systems have their genius. And you can be critical of them. The Soviet experiment was awful. The experience of capitalism in Brazil is awful. Both of them have their gifts, but they both overreach. And they overreach because their doctrine of the human is so narrow.

Both of them see human beings as homo miserabilis. That is, they see human beings as needy, and they see the market as satisfying that need or they see the state as satisfying that need. That is to really mean that all human beings in the end, given this way of understanding what it means to be human, are consumers. What goes in their mouth, what they evacuate, speeding up that process is the goal of life. Well, that is just an awful way of thinking of human beings.

Religious ways of thinking of human beings have always been much more textured than that. And certainly within my part of the Christian tradition, the teaching and at least some of the experience is always that to be human is to be in communion. It is to run from your door to the stranger and say, "Please don't pass by. Let me go and make bread for you and meat for you. Let me wash your feet, and let's eat and talk together."

To not be inclined on the street is an indication that we need to do some work, and we need to do that work which lets go of our fear.

And that—what you're describing—is not an act of charity, is it?

It's not charity at all. I think it's an act of delight. When you see the stranger, you get perked up. You say, "Hmm, I wonder who that is." Now, that should not invite us to curiosity in the sense of wanting to have our way with that person. That's problematic. But it is equally problematic to assume that you do not want to look that person in the face and greet them, because both of those positions are positions of estrangement and squander an opportunity.

I think charity is significant so we should think about it, but I'm really trying to get at something which is I think much more basically human, which is that as human beings, we are inclined towards the other. I think that's who we are. We know this deeply when we fall in love, when we are inclined towards some particular person. If we come from good families, we know it to some extent from them as well.

But to not be inclined on the street is an indication that we need to do some work, and we need to do that work which lets go of our fear. And we don't need to do it for the sake of others. We need to do it because our own life will be richer, because there'll be more communion and more delight and more surprise.

The fruit of it is always in annunciation, always learning something new, seeing the world differently. Something's being born. And the danger of a kind of sanitized city is the diminishing of those possibilities.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!