Illustration by Chris Pecora

Sprawlcast Ep 16: The segregated city

Calgary is increasingly divided by income.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!

Despite being Canada’s most prosperous major city, Calgary has quietly developed what researchers call a disturbing “geography of inequality” that poses numerous risks to the city’s future.

Most Calgarians live in areas where incomes have decreased over decades, even as incomes in Calgary have increased more rapidly than elsewhere in Canada. And income polarization is changing how we live together—or, as is becoming more common, apart from each other—in the city.

“We are seeing less and less economic mixing within neighbourhoods,” said Byron Miller, an urban political geographer at the University of Calgary. “And we are seeing more and more concentrations of low-income households in particular parts of the city and high-income households in other parts of the city.”

Miller co-authored a 2018 report on income inequality in Calgary. Following the lead of a similar project in Toronto, researchers wanted to see how income inequality was playing out spatially.

You get a society where people from different walks of life are no longer coming into contact with each other.

They found that since the 1970s, poverty in Calgary, as in Toronto, is increasingly being suburbanized even as incomes in select inner-city communities spike dramatically.

Calgary is the most income-unequal major city in Canada, according to the report. In terms of spatial income inequality, Calgary is the second-most unequal city, after Toronto.

And while choice has often been held up as the driving idea guiding urban development in Calgary—the housing market is providing what people want, and people are freely choosing where to live—the research suggests otherwise.

“Where do people who are in an economically precarious situation locate?” said Miller. “They locate, generally speaking, where the market prices are lowest. And that’s what we’re seeing in Calgary: this sorting-out of people into different parts of the city according to patterns of housing affordability.”

Donna Clarke, an organizer with the Renters Action Movement, states it more bluntly.

“The invisible hand of the market has not taken care of vulnerable people,” she said.

Calgary's 3 cities

In 1970, more than two-thirds of census tracts in Calgary were middle-income. Since then, the city has experienced a significant loss of middle-income neighbourhoods, with many post-war suburbs seeing their incomes go down. In 2010, only 41% of census tracts were middle income.

Miller worked with Ivan Townshend, a University of Lethbridge geography professor and the report's lead author, and Leslie Evans, executive director of the Federation of Calgary Communities (FCC), to understand what’s been happening over time.

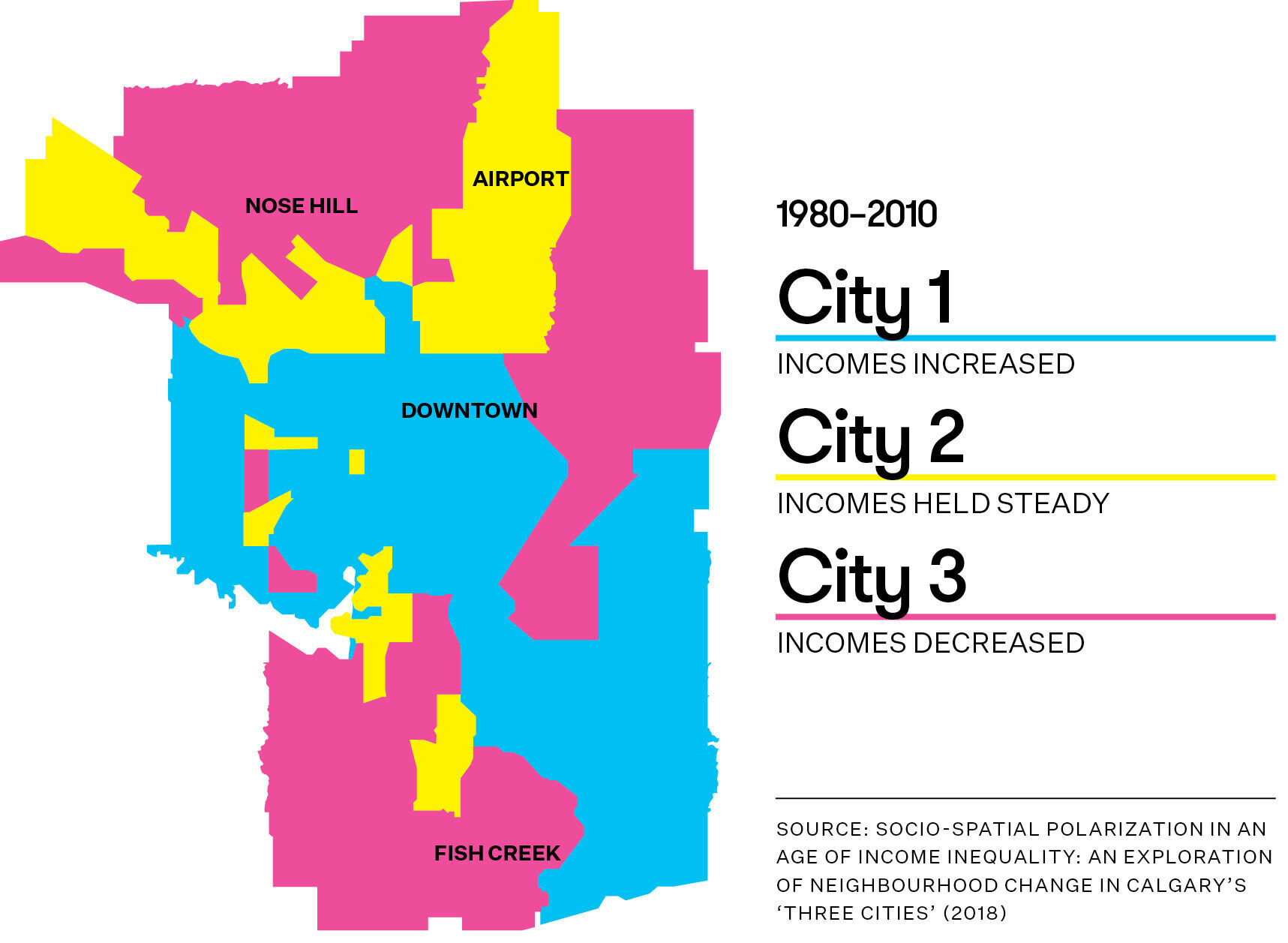

They found three distinct cities within the larger city.

In City 1, which covers much of the inner city, individual incomes relative to the city average have increased. In City 2, the smallest of the cities, incomes held steady. And in City 3—which is largely suburban, comprising 60% of the city’s population in 2010—incomes declined.

“In 2010, we see a distinctively new geography of low income, in which inner-city concentrations of poverty have given way to a vast region of low and very low income in the northeast sector of the city,” states the 2018 report, noting that the northeast has increasingly high concentrations of visible-

minority immigrants.

An updated analysis found that while Calgary household incomes went up by 31% between 1980 and 2015, affluent and poor communities didn’t see equivalent changes—making Calgary a prime example of a “dividing city.”

This poses myriad risks, as income is directly tied to health, education and other outcomes.

“Income disparity is one of the biggest predictors of other social problems,” said longtime community organizer Cesar Cala, who has been working in neighbourhoods since he arrived in Calgary from the Philippines in the mid-1990s.

“It’s something that we need to address as a city,” said Cala. “If we let it be, Calgary will become such a dichotomized city.”

The most vulnerable communities have sometimes been described as “tipping point neighbourhoods,” where social issues have the potential to compound and accelerate each other.

“But also, these are the neighbourhoods where if you’re able to support local development through a combination of good public policy and citizen-led initiatives, you can actually tip the neighbourhood back and bring them towards resiliency,” said Cala.

It’s something that we need to address as a city. If we let it be, Calgary will become such a dichotomized city.

Cala, who ran for the provincial NDP in Calgary-East, emphasizes that while deliberate investments in such areas are important, it’s key that community members are included—which leads to “deeper and long-lasting” change.

“I would draw a distinction, for instance, between development that’s happening in East Village and the development that is slowly happening in Calgary-East,” he said. “The East Village development is really more of ‘get a lot of the residents out of the picture and put in some new infrastructure.’"

"But in Calgary-East, it’s really investing in people and in the communities and the things that matter to them.”

Different cities, different needs

There is a sense of caution surrounding this research. Viewed carelessly, it could be used to stereotype certain areas of the city. “That is not the intent,” said Evans.

It's not as simple as saying City 1 is rich and City 3 is poor. Because the researchers tracked income change, an affluent neighbourhood that saw its incomes decrease could be part of City 3. Conversely, a low-income neighbourhood that saw incomes increase—but still remain low—could be part of City 1.

The deep southwest, for example, is in City 3 in large part due to seniors who have retired and are living off their pensions, says Miller.

“We’re not trying to pit the three cities against each other, and there’s definitely variability within the three cities,” said Ben Morin, an FCC urban planner. “There are people who are struggling in some of these inner communities and there are people who are doing well in the outer communities. But it’s about thinking of how these three cities fit together in terms of a policy perspective.”

No one city is better or worse off. They’re very different, and different decisions need to be made around them.

For example, spatial income inequality means that publicly-funded urban amenities—such as transit and walkability—are not equitably accessible. “Walkability has kind of become a premium for the wealthy in certain areas,” said Morin.

Evans notes that each of the three cities have different needs. City 1 needs a better mix of housing to let people in, whereas City 3 needs better

services and transit to connect people with the rest of the city.

“Those are the kinds of things we need to talk about,” Evans said. “No one city is better or worse off. They’re very different, and different decisions need to be made around them.”

She points to the Green Line as an example of where the research could help. The new LRT line will extend south into communities where incomes increased—and won’t yet extend to the north-central communities, many of which have experienced declining incomes.

“It was actually needing to go more up to the north,” Evans said. “If we could have shown this and explained this, perhaps that might influence public policy in a different way.”

Social cohesion is being eroded

The research also offers a useful lens on some of the uglier social tensions Calgary has seen in recent years, in which residents try to keep out certain people and projects to preserve neighbourhood homogeneity—or “character,” the more palatable term.

The fierce anti-renter sentiment that some Calgarians have displayed at city hall can seem bizarre. But it’s more understandable when you consider that our neighbourhoods have become polarized by income.

“You get a society where people from different walks of life are no longer coming into contact with each other, no longer know each other in any meaningful way,” said Miller. “This is a real problem for a democratic society.”

The research offers a useful lens on ugly social tensions, in which residents try to keep certain people and projects out of their neighbourhood.

While the problem is undoubtedly immense and complex, solutions are possible on the municipal, provincial and federal levels.

Affordable housing is a key component, by all accounts.

“There have been some improvements in terms of social housing provision in recent years, but they’re relatively modest,” said Miller. “We are nowhere near where we need to be in terms of providing good-quality, desirable housing for those on low incomes.”

Many of the current problems can be traced back to the dismantling of the social safety net and social housing programs since the 1980s. “We take the market as a given,” said Miller. “It’s important to keep in mind that there are societies where we also have non-market mechanisms for providing housing.”

Canada could learn from the Netherlands, he says. There, social housing accounts for more than a third of housing stock—and even more in cities.

“It’s not housing of the last resort," said Miller. "It’s considered very good and very desirable housing for the most part, and because it’s desirable, you tend to get much greater social mixing.”

I’d like to see better accommodation built so that us vulnerable, poor people — or renters — could live above ground.

Donna Clarke with the Renters Action Movement says that while city hall’s recent secondary suite reforms are welcome, it’s low-hanging fruit, as many renters would rather not live in a basement suite.

“I’d like to see better accommodation built so that us vulnerable, poor people—or renters—could live above ground,” said Clarke, adding that a lot of Calgary Housing Company units aren’t particularly appealing either. “There’s a lot of subpar housing.”

Renters Action Movement is calling on the province to bring in rent control, one tool to protect people from being pushed out of their homes and neighbourhoods by gentrification.

As long as we keep relying on the market to solve the problem, Miller says, we’ll keep seeing segregation by income.

“It’s only when residential location is not dependent upon income that you’re going to start to see greater diversity within neighbourhoods,” Miller said.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!