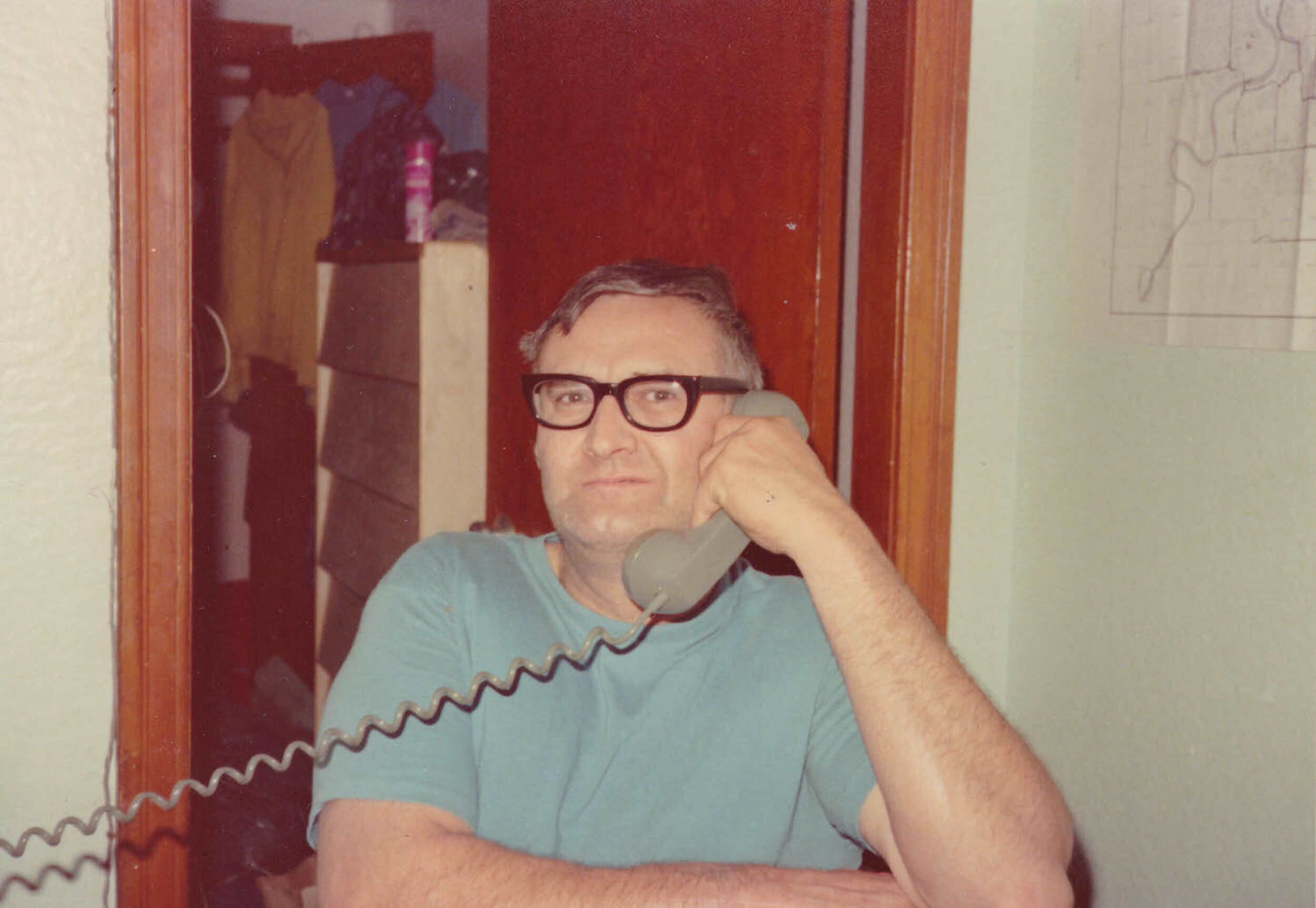

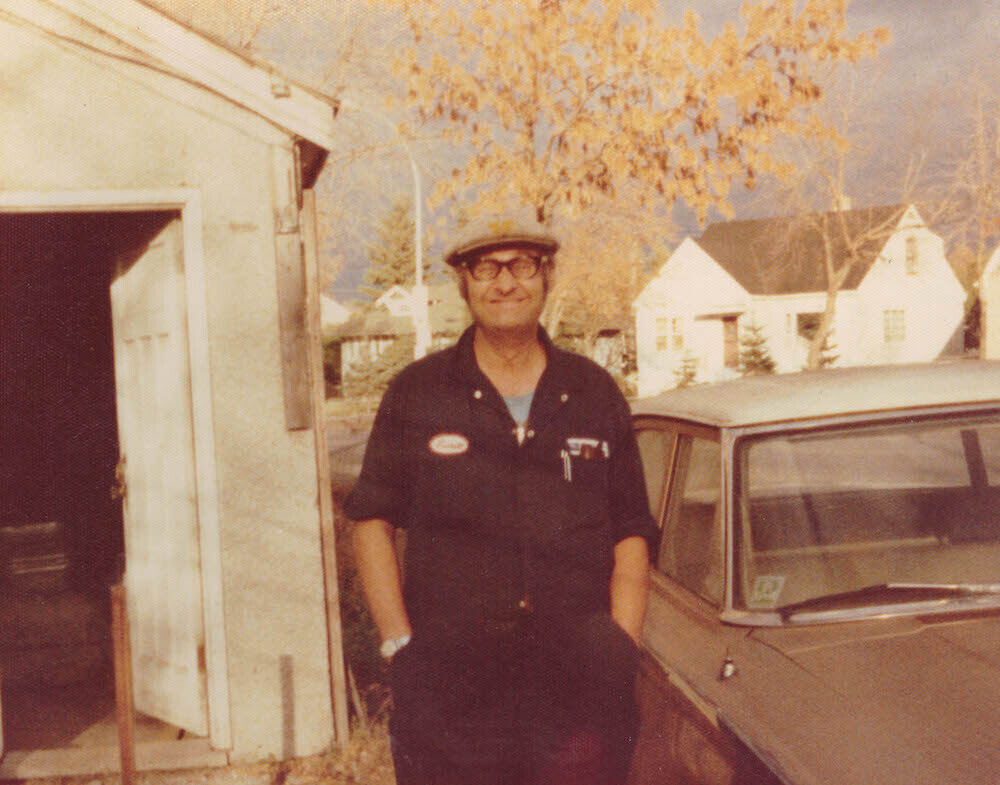

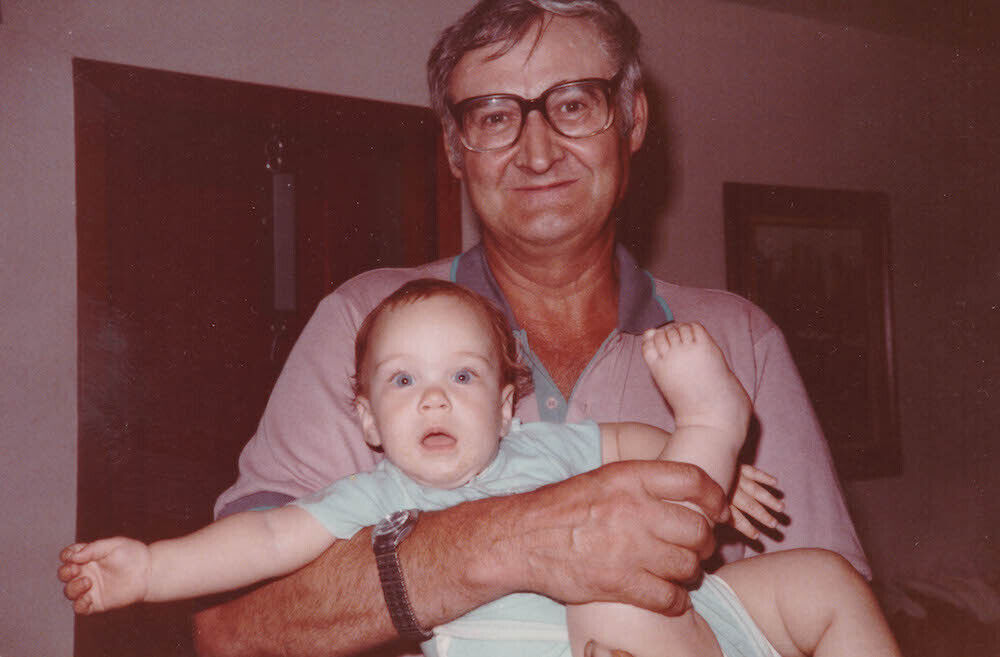

Everett Klippert. All photos courtesy of Calgary Gay History Project/Klippert Family

Why I’m celebrating 1969 and Calgary’s gay rights anti-hero

Everett Klippert changed Canadian society.

There once was a Calgary bus driver named Everett Klippert who went to jail for most of the 1960s because he was gay.

The youngest of nine children, Everett grew up in Crescent Heights. Tragically, Everett’s mother died when he was five. His adult sister Leah took it upon herself to look after her father and eight younger brothers. Leah made sure that the family kept its evangelical Christian faith. They regularly attended services at Crescent Heights Baptist Church.

School was not a priority for Everett, and he left after completing Grade 8. His father operated the Jenkins’ grocery store in Bridgeland, and Everett’s first job was working in the store along with some of his older brothers. Everett’s next position was working at Union Dairy; it was there that he had his first gay experiences at the age of 16 or 17.

After Union Dairy, he worked for eight years as a popular bus driver for Calgary Transit. There are stories of his regular passengers skipping earlier buses to specifically ride home with him due to his friendly, congenial nature.

In 1960, Calgary police discovered Everett’s homosexuality and he was incarcerated after a speedy trial.

He was 33 years old.

Klippert's battles with the state

At the time, gay Canadians were convicted in our legal system under the euphemistic charge of “gross indecency.” Released in 1964, Klippert ended up back in jail in 1965 due to more gross indecency charges. His legal battles with the state went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

In 1967, the judges made a controversial 3-2 decision upholding a lower court ruling that labeled Everett a dangerous sexual offender, worthy of incarceration for life.

This judgment, brutal and dramatic, agitated Canadian society.

It was editorialized heavily in the country’s newspapers. It was a subject at Canadian dinner tables. Underground gay communities in Canada’s largest cities listened intently to the conversation. Pierre Trudeau, then a feisty federal justice minister, stood on the steps of the House of Commons and famously declared:

"Take this thing on homosexuality. I think the view we take here is that there’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation, and I think what’s done in private between adults doesn’t concern the Criminal Code."

The judgment against Klippert, brutal and dramatic, agitated Canadian society.

Six months later, Trudeau, a newly minted Liberal leader, was decisively swept into the Prime Minister’s office on a mandate to make Canada more culturally progressive. Decriminalizing homosexuality was one of his platform policies.

His socially conservative opponents labelled him a promoter of sexual deviation and a “beast of Sodom.”

On May 14, 1969, Parliament passed Bill C-150, the Criminal Law Amendment Act. Amongst many other provisions, it specifically altered the crimes of gross indecency and buggery in private between two consenting adults aged 21 or older—a watershed moment for a human rights struggle that was just beginning.

Or was it?

The 1969 controversy

Fifty years later, a group of academics and activists have come together to denounce and minimize this event in Canadian history.

Based in Toronto, the Anti-69 Network has been actively campaigning against all celebrations and commemorations of the 50th anniversary of Bill C-150. They take particular umbrage at the use of the word “decriminalization.”

The anti-69ers make several indisputable points. The policing of queers got worse before it got better. The Criminal Code amendments only narrowly allowed for homosexual sex, and it took decades for legislation to change further.

Moreover, we have legislative and policing issues in contemporary Canadian society that still need attention and resolution. For example, there is a persistent double standard in the age of consent between anal and vaginal/oral sex (18 vs. 16).

The status of the gay Canadian before 1969 was abysmal.

However, forgotten in their analysis is that no matter how narrow the amendment was, it ran contrary to decades, indeed centuries, of beliefs and mores about queers in society and in our inherited common law system.

The status of the gay Canadian before 1969 was abysmal.

Anti-69ers, in their zeal, aim to extinguish commemorations of this human rights achievement. Their core thesis is that Bill-C-150’s positive impact on Canadian society is a myth—meaning it was untrue; it did not happen. Yet, myth has another meaning when it comes to history: a sense of the legendary.

And it begs the question, what is myth and what is truth when it comes to history?

Furthermore, what effect does presentism—the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts—have on anti-69 rhetoric?

What Bill C-150 accomplished

As a community historian engrossed for many years in Calgary’s gay history, I believe that Bill C-150 did unleash a profound change in Canadian society. It made life less dreadful for the country’s gay community; it is legislation worth commemorating.

One of the central tenets of the anti-69 argument is that the legislative changes with respect to homosexuality were too narrowly defined and furthermore never policed.

Bill C-150 added an exception clause to two provisions in the Criminal Code: gross indecency and buggery.

Bill C‑150 made life less dreadful for the country’s gay community; it is legislation worth commemorating.

This exception allowed any two adults, aged 21 years or older, in the privacy of their own home, the freedom to have consensual sex—meaning no longer just husbands and wives, and not just heterosexual sex.

The anti-69ers claim that the state did not police what happened in people’s bedrooms regardless, so the legislative change was effectively window dressing with no impact.

Yet, that was not true—at least, not in Calgary.

‘We do not need it in this country’

In 1946, Police Inspector Reg Clements, on a rumour, barged into a private downtown hotel room and found Alfred Andrew in bed with a young man. After Clements questioned the latter, Andrew was charged with gross indecency.

He pled guilty and was sentenced to six months of hard labour.

The Calgary police sought LGBTQ2 people everywhere: in public places as well as behind closed doors. In 1960, police grilled Everett Klippert in the privacy of his own home because of a homosexuality allegation by a third party. Without permission, they searched his place for damning evidence—and found some—before 18 charges of gross indecency were laid.

Notably, the state did not care where or how discreetly he had sex with men; it was the fact that he did, which was the crime.

The Calgary police sought LGBTQ2 people everywhere: in public places as well as behind closed doors.

When Bill-C150 passed in 1969, Calgary Police Chief Ken McIver said the new law represented decay in Canadian society. He was quoted saying homosexuality is "a horrible, vicious and terrible thing. We do not need it in this country."

He lived up to those words.

Police officers harassed Calgary’s early gay clubs. Gay men in the 1970s were profiled, picked up in public and jailed overnight on frivolous charges. The state was not kind to us post-1969, but Calgary queers had a beachhead now: their own bedrooms.

Gay elders alive in our community today were well aware of Bill C-150 then. For some, there was a new sense of confidence after the law changed and a belief that no more human rights actions needed undertaking. They found particularly irksome the Gay Liberation Front chapter that formed on the University of Calgary campus in 1972, which agitated for social inclusion and the end of closets.

Others noted how the Criminal Code changes affected public attitudes for the better. There was a widespread and mistaken belief amongst Canadians that gay identity itself had been made legal.

They did not understand that only narrowly defined gay sex was now permitted.

A blossoming in the 1970s

Those in our community with an organizational bent began to form the first peer support centres and many other organizations. They felt a new freedom to associate as well as to discuss sexuality publicly. Within a decade, Calgary had a visible and vibrant gay community, a 1970s blossoming that occurred in other Canadian cities as well.

In 1975, Gay Information Resources – Calgary (GIRC) wanted to advertise their organization’s phone number and peer support hours in the city’s two daily newspapers. The Calgary Herald refused, but the Albertan—which became the Calgary Sun—allowed it and commented in a direct reference to Bill C-150, “if it’s alright with Trudeau, it’s alright with us.”

Within a decade, Calgary had a visible and vibrant gay community.

The impact of decriminalization consequently went far beyond the state and its powers; it affected so many aspects of Canadian society and Canadians’ attitudes toward the gay people in their midst.

This is perhaps best illustrated by our deep identification with Trudeau’s famous quote: “There’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.”

How is it, even when the details of Everett Klippert’s story are largely forgotten, that those memorable words are so deeply embedded in our national psyche?

Canadian society pivoted at that moment on a phrase; one could argue it was even mythic, in the legendary sense.

What makes a mythic moment in history? The Stonewall riots, where the gay community unexpectedly and spontaneously fought back against New York City police harassment, seems to have mythic status. This significant event, also celebrating a 50th anniversary this summer, has grown in legend over time and now has global resonance.

Historians quibble on the details of its import and who were the primary actors on that fateful day; there is little consensus.

As time passes, one event in the summer of 1969 is elevated and magnified, while the other is reduced to a quote.

Interestingly, Stonewall hardly made mention in Canadian newsprint that summer. Especially when compared to the column inches devoted to homosexuality in the Bill C-150 debates.

As time passes, one event in the summer of 1969 is elevated and magnified, while the other is reduced to a quote. And to the anti-69ers, that quote itself should be diminished to nothingness.

Klippert's freedom from jail

But what about poor Everett Klippert? He was the anti-hero of the Canadian gay rights movement, a victim of his sexual orientation who just wanted to get out of jail. What did the summer of 1969 mean to him?

In his jailhouse diaries, he wrote in all caps on Tuesday, August 26, 1969: "THE CRIMINAL CODE CAME INTO EFFECT DUE TO MY CASE."

It was that day in history that Bill C-150 received royal assent and came into force. For that reason alone, the Criminal Code amendment should be celebrated as it secured Klippert’s eventual freedom from incarceration in 1971. He escaped his interminable life sentence.

His family petitioned his release precisely because of that important legislation.

The anti-69ers may have been successful at getting the Toronto Pride Parade to drop the 50th anniversary of decriminalization as its 2019 parade theme. They may have convinced a lot of people to disparage the Royal Canadian Mint’s commemorative equality dollar coin.

Nonetheless, they haven’t convinced me.

Between us, we have created different historical narratives using a similar set of facts. Bill C-150 was significant; Bill C-150 was insignificant. Let us wait another fifty years and see what is remembered at the 100th anniversary.

The metaphorical Supreme Court of History will be our judge.

Kevin Allen is author of Our Past Matters: Stories of Gay Calgary and the research lead of the Calgary Gay History Project.

The Sprawl is crowdfunded, ad-free and made in Calgary. Support independent journalism. Become a Sprawl member today!

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!